George Julian Harney, 1817-1897

George Julian Harney was among the first and the last Chartists – a revolutionary whose political journey through Chartism linked the ultra radical heirs of Thomas Spence in the London Democratic Association to Marx, Engels and the exiles of 1848. He ended his long life an opponent of many of the causes he had earlier advocated with such passion, yet still able to retain the affection and friendship of many in the emerging socialist and labour movement of the century’s closing years.

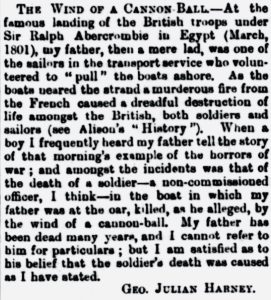

Julian Harney (almost never George) was born on 17 February 1817 into a working-class sea-faring family in the naval dockyard town of Deptford on the Kent bank of the Thames. Sources for Harney’s early years are sparse, and biographers have relied almost entirely on the few details gleaned by Edward Aveling towards the end of his long life and the few scraps he shared in newspaper columns over the years. In brief, these suggest that Harney had little education beyond dame schools and, from ages eleven to fourteen, at the Royal Naval School at Greenwich, and that Harney’s father died when he was still a boy.

A more romantic account, however, has him born actually ‘on board a troop ship lying off Deptford’. Harney’s had father served in the transport service of the Royal Navy during the Napoleonic Wars, carrying on a family tradition, and continued to work supplying navy ships after he was discharged. And according to ‘an old Newcastle friend of Mr Harney’s’ writing in the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle (10 December, p.5), Harney ‘as a child and boy spent some time on the war vessel which was then engaged in the West Indian service’.

Genealogical research shows that Harney’s father George Harney had been born locally in 1784, and married Sarah Southcott (born 1791) at St Alphage’s, Greenwich, on 19 March 1812. Julian Harney was the oldest of four children born to the couple, and at the time that he was baptised at St Paul’s Deptford, on 16 March 1817, the family lived at Back Lane, Deptford.

Contrary to some biographies, Julian Harney did not lose his parents in childhood; George lived on until 1850, and his mother Sarah to 1863. But the elder George Harney was admitted as a patient at Greenwich Hospital, and it may have been this that enabled Julian to get a place at the naval school. At the age of fourteen, Harney joined the crew of a small ship trading to Lisbon and Brazil. But, according to the account in the Newcastle Chronicle, he was ‘not robust at that age, and much of the time at Greenwich had been spent in the school infirmary’; after six months at sea sailing to Lisbon and Brazil, he decided it was not the life for him, and gave it up in search of a job ashore.

Youthful radicalism

After working briefly as a pot boy, Harney’s burgeoning interest in radical politics took him into the orbit of the National Union of the Working Classes and to a new career with the radical bookseller and publisher Henry Hetherington, selling pamphlets and running parcels of radical publications to buyers throughout the capital and further afield. In their refusal to pay stamp duty on their publications, the ‘tax on knowledge’, Hetherington, along with James Watson, Richard Carlile and other London publishers were in constant legal jeopardy, however, and despite his youth, Julian Harney faced the same dangers. By the time he was nineteen, he had served three prison terms.

Living at Horselydown Lane, Bermondsey, on the south bank of the Thames close to where Tower Bridge now stands, Harney established friendships with many veteran London radicals, among them Thomas Preston, who had worked with Thomas Hardy and Horne Tooke in the London Corresponding Society of the 1790s, and Alan Davenport, a disciple of Thomas Spence who was to become a key influence on Harney. He also came to regard the Irish radical lawyer James ‘Bronterre’ O’Brien, who had edited Hetherington’ Poor Man’s Guardian, as a ‘guide, philosopher and friend’.

Heavily influenced by O’Brien’s interpretation of French revolutionary Jacobinism, Harney became in 1837 a founder member of the East London Democratic Association (ELDA), alongside Davenport, and the republican Charles Neesom. More radical than the London Working Men’s Association (LWMA), which consciously limited its membership to the rather better-off artisans, the ELDA found much of its support among the impoverished weavers of London’s East End.

For the best part of a year, internecine manoeuvring among London’s radicals saw Harney and his comrades seek to take over the LWMA, allying themselves with the Irish radical Feargus O’Connor. But William Lovett and the leadership of the LWMA saw off the challenge, and Harney found himself with no option but to resign his LWMA membership, and in May 1838 to revive what was now the London Democratic Association. The LDA’s candidates were subsequently defeated in the election of London delegates to what would be the first Chartist convention, but even as the in-fighting continued, and O’Connor threw his full weight behind his LDA allies, Harney left the capital to seek nomination to the convention elsewhere.

Chartism

In December 1838, Harney boarded the coach for Newcastle. In The Chartist Challenge, his biography of Harney, the historian A.R. Schoyen writes that the journey conveys something of the hardships facing working-class leaders at the time. ‘Leaving London at eight in the evening of the 23rd, the coach did not toil up the steep incline from the Tyne until early in the morning of Christmas Day. During this time, stops were made only to change horses and for meals – which Harney could not afford. Riding on top of the coach through two nights and a freezing day in which snow fell, with only a leather apron buckled across his knees for warmth, he arrived in Newcastle exhausted.’

On Christmas Day 1838, Harney and others addressed a crowd some 60,000 to 80,000 strong. Arms not petitions, he told them, would win the Charter. And the Newcastle Chartists agreed: they unanimously elected Harney, along with Robert Lowery and Dr John Taylor, both firm advocates of physical force, as their delegates to the convention. Here and in the surrounding towns, Harney found a ready audience. In villages such as Winlaton, exhortations to arm were being taken seriously, and weapons were being accumulated in large numbers.

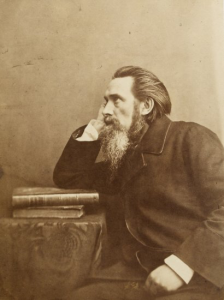

Still just 21 years old, Harney drew crowds of thousands as he toured Northumberland and Cumberland. Schoyen notes that ‘he had grown into a slender, intense man with rather delicate features, plainly marked dark brows, and brown hair, worn long in the fashion of the time’ his whole appearance enhanced by the tricolour sash or ribband that he wore. Harney was not yet ready to return to London, however, and in January 1839 he spoke at meetings across Lancashire and Yorkshire before arriving in Derby. It was here that Harney had served one of his early periods of imprisonment; now he was to be acclaimed by a revitalised radical body, and elected as their delegate to the convention.

When the convention assembled in London, Harney quickly established a small left caucus. Although the convention itself was divided from the first – both over what its role was, beyond the presentation of the first petition to parliament, and over what ulterior measures should be taken when it was inevitably rejected – this group proved influential beyond its numbers. Despite opposition from the LWMA men, the moderate middle class contingent from Birmingham, and even from O’Connor, Harney successfully persuaded the convention, which soon relocated to Birmingham, to commit itself to a series of ulterior measures that included a sacred month, or general strike.

Harney left Birmingham for Newcastle shortly before the convention adjourned on 17 May – and by chance managed to escape arrest. But a London police officer had been among the crowd when Harney had urged a general strike, and there was now a warrant in his name on charges of sedition. Despite this, on his return to the North East, Harney spoke at numerous meetings – including one perhaps 100,000 strong in Newcastle – with armed men much in evidence. Bands, long processions and festive dinners greeted his arrival in every town, and women Chartists presented him with gifts wherever he went, and formed female Chartist associations in several localities.

That July, after Harney addressed a meeting in Bedlington, some miles north of Newcastle, magistrates backed by London policemen and a troop of dragoons swooped, arresting him in the early hours of the morning (‘torn from the arms of his wife in bed,’ according to the Morning Chronicle, though Harney was unmarried), and hurried him back to Birmingham. Here, a grand jury was convened to hear the case against him – the claim of the police witness that Harney had advocated that Chartists take ‘the musket in one hand and a petition in the other’ being contradicted by six witnesses who claimed that he had said ‘biscuit’, in reference to the food required during the sacred month. After a week in Warwick Gaol awaiting the summer assizes, the grand jury decided that there was no true bill against him, and Harney was released.

Scotland

In 1840, with much of the Chartist leadership behind bars, Harney set off on tour of Scotland – a journey which almost unavoidably takes on near-mythic qualities. Travelling on foot, he covered more than two thousand miles and addressed hundreds of meetings, some attended only by small groups of Highland crofters. He lived on the small sums collected as he went, and relied on the hospitality of local supporters for bed and a meal,

One night, Harney joined the Dundee Chartists on board a specially hired boat, sailing to Perth where they paraded at dawn with a band and banners flying. At other times he was able to wax eloquent over the beauty of the Ayrshire countryside, ‘a scene lovely as Eden and beautiful as Elysium’. But he also met hostility, and at Inverness was protected from physical attack by middle-class corn law repealers only thanks to the intervention of ‘workies’.

And he would return from his adventures in April 1841 with a wife: at Mauchline in Ayrshire, Harney met and married Mary Cameron, the daughter of a radical weaver. A ‘tall beautiful woman of high spirit’, according to G.J. Holyoake, this was a meeting of minds, and she was ‘a perfect wife of an agitator’.

Yorkshire and the Northern Star

Harney returned to England in April 1841, and after visiting Feargus O’Connor in York Castle Gaol, he was appointed Sheffield correspondent for the Northern Star, and effectively the National Charter Association’s full-time organiser for the locality. Perhaps surprisingly, Harney was not a delegate to the second convention in 1842, but he was among those arrested and tried in the wake of the great strike wave – during which, once again to the surprise of many, he opposed strike action.

Harney now entered the second important phase of his involvement in Chartism, joining the Northern Star as sub-editor after O’Connor dismissed William Hill as editor and drafted the paper’s printer and publisher, Joshua Hobson, into the editor’s chair. With this role, Harney became Hobson’s deputy, and was soon in effect the paper’s editor, deciding its content and direction well before he formally took on the role in October 1845.

Harney was now at his most influential. Under his leadership, the paper developed its coverage of literature, and of international politics – establishing important links with the European radical diaspora in England. Harney had been a committed internationalist from an early age. He had met Frederick Engels as early as 1843, and Engels would become both a regular contributor to the Star and a lifelong friend. These international links flourished after O’Connor moved the Star to London in 1845, enabling Harney to engage with a wide range of activists from Poland, France, Germany and elsewhere through his new organisation, the Fraternal Democrats.

Once again when a Chartist revival came in 1848, however, Harney played relatively little part other than as editor of the Star. But his thinking was moving on, and in tandem with his Star deputy, Ernest Jones, who would shortly be heading to prison for the next two years, Harney adopted a new slogan: ‘The Charter and Something More’. And as Chartism moved, at least partly under Harney’s influence, to adopt a socialist perspective, the rifts between editor and proprietor widened. O’Connor was no socialist and had little taste for European revolutionaries, and a final break came in May 1850.

Red republicans and frightful hobgoblins

Harney now launched his own Red Republican. That November, the paper would publish the first translation of the Communist Manifesto, attributed to ‘Howard Morton’, but actually the work of Helen Macfarlane. Its opening sentence, quite different to that known from later translations, began: ‘A frightful hobgoblin stalks throughout Europe.’

Despite this, a new rift opened with Marx and Engels, who disliked Harney’s indiscriminate support for radical exiles of many different political persuasions, and came to a head at New Year 1851 when Mary Harney and Helen Macfarlane had a very public falling out. In a letter to Marx in February that year, Engels would accuse Mary of a ‘prediliction’ for the likes of Louis Blanc (whom both Marx and Engels detested), and claimed that her husband was in thrall ‘to this spiritus familiaris, and of the petty Scottish wiliness with which she conducts her intrigues’. Whatever the cause of the argument, it led Macfarlane to quit Harney’s paper (now renamed the Friend of the People), robbing it of ‘the only collaborator on his insignificant little rag who really had any ideas’. It would be some years before the old friendship between Engels and Harney was renewed.

Further divisions followed Jones’s release from prison, the fallout of which left Harney in alliance with the remnants of the London-based National Charter Association executive committee, while Jones established new ‘Chartist’ bodies of his own in Manchester. Perhaps the final blow for Harney at this stage of his life came in February 1853, when the 35-year-old Mary Harney died. She is commemorated by a memorial in the churchyard at Mauchline.

Jersey and the United States

In October 1855, Harney left England for Jersey, ostensibly to investigate the political situation at the instigation of the Tyneside Foreign Affairs Committee. Once there, however, he began a new life, once more found himself a newspaper to edit, and married once more – to Marie Metivier (nee Le Sueur), widow of a draper. With a new job, and his new wife and stepson, Harney lived in some comfort on the island. His time there is recorded on the Jerripedia website. But in due course he found it stifling and in 1863 he and his family left for Massachusetts.

There, Harney spent the best part of fourteen years in some obscurity, as the clerk in charge of public documents in the Secretary’s Office of the Massachusetts State House. But he did maintain his links with home, visiting in 1878 and from 1884-86, while contributing to the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle, now edited by W.E. Adams, a former Harney protégé.

Decline

Harney returned permanently to England in 1888. Marie Harney, a teacher long before she met Julian, would remain in Massachusetts, where she ran a successful language school. She would visit her husband most years, and the two remained as close as it was possible to be under the circumstances, but the relationship must have been difficult to maintain.

By now, Harney was over seventy years old and in declining health, the arthritis that affected him worsening over the years, first preventing him from holding a pen, and eventually confining him to a bath chair. And the political world had moved on. Harney continued to write for his old friend Adams, but while he still regarded himself as an ‘old Chartist’, his views had changed. Harney took strongly against Gladstonian liberalism, opposing the Irish home rule he had once supported enthusiastically, criticising trade unions and strikes where once he had advocated the sacred month, and voicing views on the proper treatment of prisoners that would surely have appalled his younger, imprisoned self.

By 1897, Harney had moved to 2 Clarence Villas, St Mary’s Grove, Richmond, where he occupied a single room and increasingly required nursing care. Marie crossed the Atlantic and stayed with him in those final months, but he also continued to enjoy visits from his political friends. Edward Aveling, the journalist and son-in-law of Karl Marx, had come to interview him towards the end of 1896. The write-up, which appeared in the first issue of The Social-Democrat, is most notable for its description of Harney’s room:

‘I do not think I can give any better idea of the intellectual, moral, and political characteristics of Harney than by telling the reader of the portraits and the like that crowd his walls. I take them just as I saw them, working round his room. Fergus O’Connor; Frost; Joseph Cowen; Oastler, the Factory King; “Knife and Fork” Stephens, the physical force man, who spent eighteen months in Chester Castle; W. J. Linton, engraver and Chartist; Harney himself (he is even now a delightful bit of a beau in his way, as scrupulously dressed and groomed as ever), as a Yankee, with a moustache only, instead of the present venerable beard ; Lovett, who drew up the People’s Charter; Frederick Engels and Karl Marx, very fitly side by side (Harney had the high honour of their friendship); “Ironsides” Adams, of the Newcastle Chronicle. All these are on the walls by his bed and the fireplace that runs to the window, looking south. Over the mantlepiece is a group that reminds some of us younger workers in the workers’ movement that perhaps we hardly pay as much attention to pure literatura as our political forefathers did—Byron, Scott, Burns, Shelley, Moore, Pope, Dryden, the grave of Fielding, and, high over all, Shakespeare. Between the windows looking south are Miss Eleanor Cobbett, now ninety-one years of age, a letter from Cobbett himself, and the People’s Charter. Between the windows and the door, Magna Charta, Darwin, Ruskin, Sidney, Chaucer, Raleigh, De Stael, Mary Wollstonecroft, together with a bust of Shakespeare again. And, by the door, there is a picture of Uncle Toby and the Widow Wadman.’

Here, at Clarence Villas on 9 December, 1897, Harney died.

A final farewell

There are few accounts of Harney’s funeral, for few were there to record the event. The Newcastle Weekly Chronicle, to which he had contributed so many weekly columns to within a short time of his death, sent a reporter and representatives from its London office. Among the mourners in the three coaches which followed the coffin from St Mary’s Grove were his widow, a nephew and niece, and a few friends and neighbours.

Karl Blind, the German writer, veteran of the 1848 revolutions and a long-time friend of Harney’s, had been expected to say some words, but lost his wife a few days before the funeral and was unable to be there. Gerald Massey, another ageing Chartist, was kept away by illness, ‘while the wretchedly damp and muggy weather helped to further deplete the attendance’ (Newcastle Weekly Chronicle, p.5, 14 December 1897).

However, the Rev. Joseph McKim, who conducted the service, ‘made kindly reference to Mr Harney’s life and work’, adding that ‘there could be no doubt that he had steadily worked for the welfare and brotherhood of mankind’. ‘Having been conveyed to its last resting place – on the summit of a breezy elevation – the flower-laden coffin was lowered into the earth and the company then dispersed.’ Among those sending flowers were Harney’s grandchildren in Waltham, Massachusetts.

As the Chronicle reported: ‘It only remains to add that a brass plate on the lid of the coffin contained this simple inscription – “George Julian Harney; born 17th February 1817; died 9th December 1897”.’

Sources and further reading

Books

The Chartist Challenge, by A.R.Schoyen (Heinemann, 1958) is the only full length biography of Harney. It is both an excellent read and an indispensable source, although written before the discovery and publication of Harney’s personal correspondence.

The Harney Papers, edited by Frank Gees-Black and Renee Metivier Black (International Institute of Social History, 1969) brings together a vast quantity of letters written to and by Harney throughout his adult life.

George Julian Harney: The Chartists Were Right, edited by David Goodway, offers selections from Harney’s columns for the Newcastle Weekly Chronicle, 1890-97 (Merlin Press, 2014).

Biographical dictionaries

‘Harney, (George) Julian’ by David Goodway, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23 September 2004) (accessed 13 August 2023).

‘Harney, George Julian (1817-1897)’ by David Goodway, Dictionary of Labour Biography, vol 10, (Macmillan, 2000).

‘Harney, George Julian (1817-1897)’ by Duane Anderson, Biographical Dictionary of Modern British Radicals, vol II, 1830-1870 (Harvester Press, 1984).

Articles and blog posts

‘George Julian Harney: A Straggler of 1848‘ by Edward Aveling, The Social-Democrat vol 1. No. 1, January 1897, on the Marxist Internet Archive (accessed 12 August 2023).

‘The Chartist, his lawyer and a matter “of vital importance”’ by Mark Crail on the Society for the Study of Labour History website (accessed 13 August 2023)