Carpenters Hall and the Manchester Chartists

For more than a decade, Manchester’s Chartists were able to lay claim to one of the largest indoor meeting spaces in the town. With a capacity of thousands, Carpenters Hall was a building to boast about – and it long outlasted the Chartist movement.

The Manchester Chartists were nothing if not proud of their meeting place at Carpenters Hall. An important focal point for working-class radicalism and organisation throughout the 1840s, it was big enough to accommodate the crowds wanting to see big name Chartist speakers, including Feargus O’Connor who regularly spoke there, while in a more sedate mode it hosted tea parties, dinners and dances in its light and airy main saloon room.

For some, the hall’s very existence also offered an opportunity to take the moral high ground. When Stockport Chartist Thomas Clark moved a resolution at the 1846 Chartist convention opposing the use of public houses for lectures and public meetings, he argued that he had ‘seen the evils of meetings held in public houses in London’ where Chartists ‘sat and smoked their pipes and drank their ale’ to the detriment of the Chartist cause. Manchester Chartist Daniel Donovan agreed: ‘Instead of meeting in pot houses, they took Carpenters Hall at a rent of £80 a year, for one night in the week, and it was that step which caused Manchester to take the lead in the Chartist movement, far above the metropolis’ (Northern Star, 15 August 1846, p2).

A trade union project

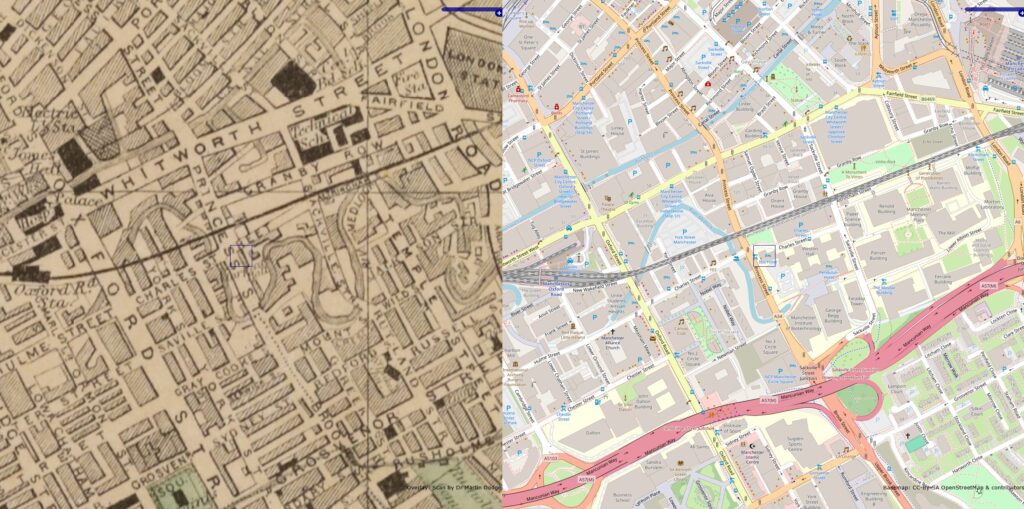

Opened in 1838, and standing on the corner of what was then variously called Brook Street or Garratt Road (now part of Princess Street) and Charles Street, Carpenters Hall was built at a cost of £4,500 by the Manchester operative carpenters and Joiners, and was paid for entirely out of union funds, according to the Manchester Courier (17 November 1838, p3). And it was an impressive sight.

The paper reported that the ground floor consisted of six or seven shops fronting Brook Street, behind which were dwelling-houses, presumably for the shopkeepers. Above them, and ‘extending to nearly the full dimensions of the building’, was a huge ‘saloon’ in which the union planned to hold public meetings, adding in anticipation of income to offset the construction and running costs, that it was also well adapted for exhibitions, balls and concerts.

According to the Courier, the main hall where meetings were to be held was 87 feet 6 inches long by 57 feet wide. At one end, there was a balcony across the whole width ‘like the galleries of churches’ with five banked tiers of seats in the middle and six or seven rows at each end. The Courier judged that the room was well lighted by day by long side windows, and in the evening by six bronze gas candelabras, each of six large argan burners. At the other end was a raised, semi-circular dais or platform for speakers.

The paper estimated that the gallery alone could hold 250 people, and was lit by two additional argand branches. And it calculated that the main hall had room for an audience of 2,200 at four people standing per square yard. This is, in fact, a very similar calculation to that used today in crowd safety and risk analysis, and is probably a reliable figure. The estimate did, however, tend to grow in the telling. The Northern Star put the hall’s capacity ‘near five thousand’ (1 June 1839, p4), while an advertisement in the Manchester and Salford Advertiser, admittedly placed before the hall was completed, suggested a frankly unlikely 6,000 (4 August 1838, p4).

R.J. Richardson, Chartist and carpenters’ union leader

That advert gives the first indication of Chartist involvement in the project, naming the Salford Chartist R.J. Richardson as ‘acting trustee to the proprietors’ and the first point of contact for those wanting to rent the hall. And as preparations were made for the first Chartist convention, it was Richardson who convened a caucus meeting for delegates from the Northern counties to ‘adopt preliminary measures previous to the assembling of the general Convention in London’ (NS, 29 December 1838, p1). A carpenter by trade, Richardson was a significant figure in local radicalism. Active in many varied causes throughout the 1830s, he was by this time the secretary of both Manchester Trades Council and South Lancashire Anti-Poor Law Association, and well placed to align trade union and Chartist movements locally.

The focus moved south in early 1839, to the Convention’s meetings first in London and then in Birmingham. But on 5 July as delegates moved towards calling for a ‘sacred month’ or general strike, Richardson resigned from the Convention, calling the strike a ‘rash foolish experiment’ that would bring ruin on hundreds of thousands of people. By 12 August, the date set for the strike to begin, it had been scaled back to a three-day ‘national holiday’. Some factories closed and there were sometimes violent clashes with the police and army, but in Manchester as elsewhere the strike was poorly supported and had petered out by day three.

After the first convention

Despite the setbacks of that year, Carpenters Hall continued to host Chartist meetings. On the eve of the strike, the Rev William Vickers Jackson, a Stockport Methodist preacher who had already been arrested and charged with conspiracy and sedition and was then awaiting trial, delivered two ‘farewell sermons’ to large audiences there (NS, 17 August 1839, p8). The services concluded with singing and prayers.

The following month, on a Saturday afternoon, Feargus O’Connor was on the bill at Carpenters Hall, which was ‘completely crammed’ with supporters who gave him a tumultuous welcome, ‘waving their hats and clapping their hands for several minutes’ (NS, 17 August 1839, p7). O’Connor gave them exactly what they wanted, and ‘addressed the meeting for nearly two hours in a most rapid and energetic style, defying at times all efforts of reporting’ before sitting down to ‘renewed and enthusiastic cheers’.

A few days later, the hall hosted a ‘radical tea party’ in aid of Chartists arrested that summer and then facing trial at Liverpool and Chester. Upwards of 600 men and women ‘sat down to an excellent tea, provided by Mr Outhwaite the manager of the Hall’ (NS, 28 September, p1). Among the speakers were Matthew Fletcher, Bury’s delegate at the National Convention; Abel Heywood, the Manchester radical printer and bookseller; and James Leach and William Gillman of the Manchester Political Union.

O’Connor was back again in early November for a ‘radical tea drinking’ to mark the birthday of the radical orator Henry Hunt. More than 500 tickets were sold, with those unable to get in on the day offering up to twice the admission price for a chance to see the Chartist leader (NS, 9 November 1839, p1). There were, the Northern Star reported, ‘a great many females present’, and after Abel Heywood introduced him, O’Connor took the stage amid a tremendous round of cheering ‘which literally made the building tremble’. Further such meetings followed the arrest and trial of the leaders of the Newport Rising that winter.

Catholics, Mormons and the Irish Liberator

The hall continued to provide a venue for large-scale Chartist meetings. April 1840 saw a debate there between Chartists and the Anti-Corn Law Society, and that August, a procession led by radical and trade union banners and bands made its way through Manchester’s streets to Carpenters Hall where Peter Murray McDouall, who had been Ashton-under-Lyne’s delegate to the first convention and was newly released from gaol, was guest of honour (NS, 22 August 1840, p7).

Chartists were not the only body to meet at Carpenters Hall. In July 1840, there was a meeting called by the trades to support the Stockport weavers in their efforts to prevent pay cuts; the town’s Roman Catholic community hired it out for their own use; and the growing Mormon sect used it for conferences at which Brigham Young addressed them on plans for a large-scale migration of members to the Zion of the United States. After a Wesleyan Methodist debated an Elder of the Latter Day Saints on whether or not the Book of Mormon was true, the Northern Star warned its readers to ‘be on their guard, and not be duped again out of sixpence each for admittance to hear such senseless jargon, and likewise to make such bad use of their precious time’ (NS, 17 October 1840, p8). It is perhaps worth noting that Mormons and Methodists fished for recruits in much the same poverty-stricken working-class milieu as Manchester’s Chartists.

The biggest challenge, however, came from the Irish Repeal leader Daniel O’Connell, known as ‘the Liberator’, who spoke there to a huge rapturous crowd drawn largely from Manchester’s Irish community during the general election of 1841. The Northern Star declared implausibly that the meeting was ‘not a quarter filled’ (NS, 5 June 1841, p1). In the days that followed there were violent clashes between Chartists and O’Connell’s supporters at Carpenters Hall and elsewhere in the town. The Manchester Courier put the blame on the Anti-Corn Law League, which backed O’Connell, claiming: ‘They hired two or three hundred of the biggest and most savage Irish ragamuffins, from the purlieus of St George’s-road and Little Ireland; and having placed large bludgeons in their hands, stationed them in groups of a dozen or twenty, on different parts of the ground in the vicinity of the hustings. These wretches, being primed with bad gin and Irish whisky, were soon fit for any service on which they might be commanded, and they proved themselves worthy of their employers’ (5 June 1841, p5). At least eleven Chartists were carried off to hospital bleeding profusely from head wounds after the Irish attacked their position at the hustings, destroying the Chartist banners and driving them out of Stephenson’s Square. Observers noted that the police stood by and failed to intervene.

Chartists would continue to use Carpenters Hall throughout the 1840s. O’Connor was a regular speaker, and during the general strike wave of August 1842, the building was also an important place to hold meetings and co-ordinate action. As in 1839, the strike issue created tensions between the trades and the Chartist leadership, some of whom sought to distance themselves from what they saw as an employer trap. But once order was restored, the authorities rounded up Chartists and trade unionists alike, among them O’Connor and fifty-eight others who were subsequently put on trial at Lancaster on charges of inciting riots, risings, strikes and disorder.

After the Chartists: ‘leave your clogs downstairs’

Despite a final attempt to revive Chartist organisation there at the very start of the new decade (Manchester Courier, 26 January 1850, p), the Chartists themselves now had little need for such a large meeting place, and it was mainly used by various trade unions and friendly societies. In 1852, the ‘new model’ Amalgamated Society of Engineers ran its campaign against the employers’ anti-trade union lockout from the hall, and a new generation of trade union leaders appeared on its platforms, among them George Odger, the secretary of London Trades Council and a leading figure in the new Trades Union Congress.

Later in the century there were attempts to rename the building St George’s Hall or the Music Hall, though judging by the frequency with which the old name continues to appear in the local press, it would still be known as Carpenters Hall for decades to come. It did, however, eventually find a new purpose as a dancehall for young working-class Mancunians. Unsurprisingly, polite society was unimpressed, one newspaper claiming that there was a printed notice at the door reading, ‘No ladies admitted in bedgowns, and gentlemen are requested to leave their clogs downstairs’ (Athletic News, 8 September 1877, p4).

Carpenters Hall was still there, crouched above its row of shops, into the twentieth century, its Chartist associations now a matter of historical anecdote (Manchester Evening News, 14 October 1905, p6). Its final mention is in an advertisement offering bricks, slates, boards, spars, planks, beams and doors for sale from Carpenters Hall, Princess-street (Manchester Evening News, 5 April 1919, p4). The salvageable debris, perhaps, of its demolition

Notes and sources

All newspapers referenced in the text are found in the British Newspaper Archive. After the first mention, the Northern Star is cited as NS with the relevant publication date.

Biographical details for R.J. Richardson are taken from Chartism and the Chartists in Manchester and Salford, by Paul Pickering (Macmillan, 1995) p37.

The Rev William Vickers Jackson’s prayers proved ineffective. He was gaoled for eighteen months for conspiracy and sedition.

Jan Harris’ MA thesis ‘Mormons in Victorian England’ (April 1987) focuses on the members of the Manchester branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day saints from 1838 to 1860. It can be found in the Brigham Young University scholars archive (accessed here, 23 March 2025).