Leeds convention, 1846 – gearing up for a general election

This page looks at the Chartist convention of 1846 organised by the National Charter Association in Leeds.

The National Charter Association’s 1846 convention began with the dramatic expulsion of one of the movement’s best known figures. But its most significant achievement was to establish a national body to coordinate Chartist interventions in parliamentary elections.

With the pro Chartist MP Thomas Slingsby Duncombe as president, the National Central Registration and Elections Committee, as the new body was known, gave the NCA the means to intervene effectively on a national basis in the 1847 general election in ways that had previously been beyond it. Although the committee was to fall far short of its aim of getting 20 to 30 “Duncombite” MPs elected of whom 12 would be active Chartists, it did back nine successful radical-liberals and to its surprise saw Feargus O’Connor returned to Parliament as MP for Nottingham.

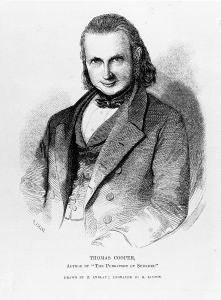

The Leeds convention had not begun well – largely thanks to Thomas Cooper, who had come to the fore in Leicester as an ultra radical and fervent supporter of O’Connor. Cooper had been arrested after the Potteries riots of 1842 and convicted the following May of seditious conspiracy. In prison, he underwent a change of heart, emerging as a vociferous critic of O’Connor, and in particular his handling of the movement’s finances.

Anxious to bring Cooper back into the fold, O’Connor attempted a reprochement, and for a time appeared to have succeeded. However, Cooper had also abandoned his previous support for the use of physical force to achieve the Charter, adopting a position of passive obedience and absolute non-resistance to authority, and was determined that the NCA should follow suit.

The convention was held in the Bazaar – a fish market and shambles near to Briggate in the town centre, which must sure have added a certain something to the atmosphere of the gathering. But no sooner had the meeting opened on the morning of Monday 3 August 1846 than objections were made to the credentials of Cooper, representing the City of London, and William Jackson, the delegate for Bradford. After some discussion a committee of five members of the convention – Grassby, Yardley, Barker, Wild and Tattersall – were appointed to investigate.

Cooper and the convention remained at loggerheads. Rising, ostensibly to move an amendment to O’Connor’s resolution in support of Chartist candidates standing at the next general election, he instead lectured delegates on “extraneous matter”, as the Northern Star put it (8 August 1846) until told he had used up his allotted time. Since Cooper’s “extraneous matter” was actually a demand for the repudiation of O’Connor and the Northern Star and for the separation of the Land Campaign from the NCA, his intervention caused uproar.

That afternoon, the committee appointed to investigate Cooper’s credentials reported back that he had refused to meet them and urged his exclusion from the convention until he cooperated. Cooper denied having refused to attend sessions of the committee, but the committee stood by its report. Ernest Jones, backed by Mooney, moved that he be expelled. The resolution was carried unanimously.

This was not entirely the end of the story. The following morning, Cooper showed up at the meeting room and had to be turned away. The convention duly appointed two door-keepers, James Thornton and John Berry, “to prevent the intrusion of disorderly and improper characters”, as the Northern Star reported. That morning, the convention went on to expel Cooper from the National Charter Association by 28 votes to five.

Moving on to the main business of the convention, delegates reported on Chartism’s electoral prospects in their areas. Bawden of Halifax stated that the Chartists had “considerable electoral power” in Halifax and did not doubt that it would be able to get Ernest Jones elected. Linney said that in Bilston, Wolverhampton, Birmingham and elsewhere they would be able to carry a candidate on a show of hands.

That alone, however, would not be enough, since they would then lose if a proper poll was then called, limited just to qualified electors. As the Chartist historian Professor Malcolm Chase pointed out in his book The Chartists: perspectives and legacies, “Chartism was by definition a movement of the disfranchised”.

The problem was well understood. As the Northern Star reported: “Mr Donovan was in favour of the measure being carried out in those places where there were favourable opportunities; in Manchester they had registered 450 claims [on behalf of individuals claiming the right to vote], but they had been rejected by the Revising Barrister, and they were not prepared with the means to carry the question into a court of law; he was unfavourable to the funds being expended merely in making a triumphant show of hands at the hustings.”

The proposal to establish an elections committee was passed with just one vote against. The Northern Star does not name the dissenter.

O’Connor then went on to call for preparations to begin on a new national petition for the Charter. This too was carried, and in time would lead to the events of 1848. A further centralising move proposed by the Leeds delegate William Brook, to change the rules so that only NCA members who had paid a shilling membership fee each year could vote in internal matters, was rejected by a single vote.

And with that, after three days of deliberation, “After the discussion of some financial matters, relative to the salaries of delegates, and the payment of travelling expenses, the Convention adjourned.”

Stephen Roberts article The later radical career of Thomas Cooper c1845-1855, Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society, volume 64, (1990), provides an excellent account of Cooper’s shifting ideological viewpoint.

Delegates to the Leeds Chartist Convention of 1846 are listed in the Chartist Ancestors Databank.