Thomas Slingsby Duncombe 1796 – 1861

Thomas Slingsby Duncombe was the best and most reliable advocate that the Chartist cause had in Parliament.

In a long parliamentary career, “Honest Tom” Duncombe spoke up consistently for radical causes, introducing the second Chartist petition to the House of Commons in 1842, campaigning against the poor laws, exposing the appalling treatment of prisoners in the Thames hulks and of the mentally ill. He voted to end slavery in the British empire, and at his death in 1861, tributes were paid to his long involvement in the cause of religious freedom and for the repeal of church taxes.

Outside Parliament, too, he was a regular speaker at trade union events and served for seven years as president of the National Association of United Trades. And he accepted the thankless task of presiding over the National Charter Association’s national central registration and elections committee, which decided which parliamentary candidates would receive the endorsement – and financial support – of the Chartist movement.

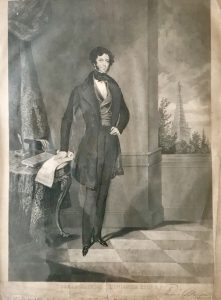

Yet Duncombe was in many ways an unlikely radical. The scion of a staunchly Tory Yorkshire gentry family, he became known as the best dressed man in the House of Commons, was as at home in the clubs of Mayfair as on the platforms of radical causes, and led a libertine lifestyle distinctly at odds with the emerging morality of Victorian society.

His biography in magisterial and authoritative The History of Parliament: The House of Commons, 1820–1832 records:

“He developed a reputation as a dandy, with a voracious appetite for women of dubious reputation and an addiction to heavy gambling, both in the gaming room and on the racecourse, where he proved himself to be one of the most talented gentleman jockeys in the country.”

But while Duncombe was ever popular in fashionable society, he lacked either skill or luck at the gambling table, repeatedly losing enormous sums. Arrested for debt in 1847, he was able to get himself discharged from custody only by claiming parliamentary privilege. And when Duncombe’s father died the following year, the entailed estates were sold for £130,000 – all of which went to pay his debts.

Unlike Feargus O’Connor, who never shrank from identifying himself with the working men who made up the bulk of Chartist support, even wearing a suit of fustian work clothes on his stage-managed release from gaol, Tom Duncombe maintained his distance, not just playing but living the part of the last of the Regency dandies.

At the time of his death, one admittedly hostile newspaper (Morning Post, 15 November 1861) noted:

“Thomas Slinsgby Duncombe, though theoretically democratic and patriotic, was by birth, manners and social position one of the ‘upper ten thousand,’ and wo betide the Finsbury shopkeeper who presumed to accost him in the familiar style of equality and fraternity – except on the hustings.”

Born in 1796, Duncombe was the son of a Yorkshire landowner and grandson on his mother’s side of the Bishop of Peterborough. His father’s elder brother had been created Lord Feversham, but the family was well to do rather than aristocratic. Duncombe himself attended Harrow school, leaving in 1811 to take up a commission in the Coldstream Guards where he served as aide-de-camp to General Sir Ronald Ferguson, himself an advanced liberal MP and supporter of triennial parliaments and the ballot. Muster rolls from 1815 show Duncombe as an ensign in the second regiment of foot.

Leaving the army with the rank of lieutenant in 1819, Duncombe ran for Parliament as a Whig in 1820, but was rejected by the voters of Pontefract. He stood again successfully for Hertford in 1826, 1830 and 1831, spending an estimated £40,000 in the process. But he was outspent by the Tory Marquis of Salisbury the following year and in 1832 lost his parliamentary seat. The many and varied causes he took up during those two years are, however, set out in some detail here.

Following the Reform Act of 1832, Duncombe returned to Parliament representing the newly created metropolitan borough of Finsbury on the northern edge of the City of London. He would hold the seat until his death in 1861.

As the MP for one of the most radical constituencies in the country, Duncombe was free – even expected – to take up the causes advocated by his electors, and indeed by the many non-electors still excluded from the franchise by the 1832 Act. This Duncombe did with some enthusiasm. In 1840, he tabled a measure in the House of Commons to try to prevent the transportation of the leaders of the Newport rising, but their ship sailed all the same – one of many causes in which was to find himself in the minority during his long parliamentary career.

With William Lovett, Feargus O’Connor and other national and local leaders imprisoned during 1840 and into 1841, Duncombe presented numerous petitions seeking better prison conditions or pardons, keeping the plight of the Chartist “martyrs” in front of the Home Secretary, Parliament and the wider public, and earning himself the gratitude and respect of the Chartist movement.

This campaign reached its peak on 25 May 1841, when a national petition was presented to MPs. Carried with great ceremony from the Chartist meeting rooms at 55 Old Bailey by a team of stonemasons, and rolled “like a giant snowball” through the lobby to the door of the House of Commons, the petition had been signed by more than 1.3 million people.

Duncombe presented and spoke in favour of the petition, which then went to a vote, being rejected solely on the casting vote of the speaker.

A year later, it was Duncombe once again who presented the 1842 Chartist petition – this time with a 3.3 million names, necessitating the removal of the doors of the House of Commons to get it in to the Chamber. In his speech, which can still be read today in Hansard (here and here), Duncombe enumerated the thousands of signatures that had been collected in towns and cities across the country.

It was, of course, to no avail. His motion for the petitioners to be heard at the bar of the House of Commons was rejected by 287 votes to 49.

Duncombe continued to support Chartism and the wider radical cause, both in Parliament and in the wider world, but was often in poor health, suffering from bronchial problems which left him increasingly debilitated and emaciated in appearance. In the late 1840s he was often took sick to attend Parliament regularly.

However, after leading opposition in Parliament to a Masters and Servants Bill which would have tightened up the law on trade unions, he was involved in the calling of a “Trades Parliament” at Easter 1845 which led to the foundation of the National Association of United Trades – a loose federation of trade unions linked to the Chartist cause, serving as its president until 1852.

The private life of Thomas Slingsby Duncombe

Duncombe’s life outside Parliament in the latter years of his life is intriguing. Despite having gambled away the family fortune (or perhaps because of it it), he remained popular on the social circuit – and clearly found money somewhere. He maintained a bachelor apartment at the Albany, then as now an exclusive London address frequented largely by wealthy single men.

But as the 1861 census shows, he also had a town house at 3 Sussex Gardens in Paddington. The building is long gone and a row of shops now stands on the site, but it was clearly a desirable address; Duncombe’s neighbours included a retired medical doctor, solicitor, commercial merchant and fundholder. There were two live-in servants: a housekeeper and a footman.

The census, conducted on the night of 7 April, found Duncombe at home. Louisa Duncombe, “proprietor of house property”, was also present, although the census describes both as unmarried and lists her as a visitor. So was she a relative – perhaps a sister or cousin? The truth is more interesting.

Two weeks after the census, on 21 April 1861, Thomas Slingsby Duncombe and Louisa Ann Draper were married at Kensington register office; both gave 3 Sussex Gardens as their address.

For all his reputation as a libertine and a ladies’ man, it appears that Duncombe had been in what we might today call a long-term relationship for decades. Duncombe had a son, also Thomas; in the 1871 census, both Louisa Draper (now aged 60) and the younger Tom Duncombe (aged 30) were at the same address – he listed has householder, her as “mother”. So the newly-weds of 1861 had clearly known each other for at least 20 years.

The marriage did not last long, and perhaps after all those years it was the state of Duncombe’s health which had prompted the decision to wed. In the autumn of 1861 he told the Clerkenwell News, which covered his constituency and was friendly in its coverage of him, that he “was about to remove to Lancing, near Shoreham, to escape the November fogs”, and asked its staff to keep him informed of events in Finsbury.

There, on 13 November 1861, he died.

Duncombe’s remains were returned to his London house, “the entire arrangements being under the direction of Mr George Shillibeer, of North-street Quadrant, Brighton, and 40, City-road, London”.

The Clerkenwell News helpfully advised its readers that:

“Sussex—gardens is in a road running out of the Edgeware-road, opposite to the ‘Marylebone’ or ‘New Road.’ It is the last row of mansions on the right-hand side, below Cambridge-terrace.”

Later, the Morning Chronicle reported (22 November 1861):

“The remains of the deceased having been place in an elm shell, that was encased in a leaden coffin, the outer coffin being of oak, covered with black cloth, richly ornamented with brass nails and furniture. The funeral procession consisting of a hearse and four horses, with two carriages and pair, left the house of the deceased shortly after ten o’clock, and arrived at the Kensal Green Cemetery at twelve o’clock. The funeral was strictly private – the son of the deceased, his two brothers, and Mr Graham, his proposer at his elections, occupying the first carriages; Mr Smith and three other gentlemen being in the second. The grave of the deceased is of brick, on the open ground on the north side of the cemetery, immediately between the vault where rest the remains of Lord Palmerston’s sister, Mrs Bowles, and the vault of Mr F. Huth, the eminent merchant. The inscription on the coffin was as follows:- ‘Thomas Slingsby Duncombe, died 13 November, 1861, in the sixty-sixth year of his age.’ Upwards of 600 persons assembled at the cemetery, and followed the body to its final resting place, and among them we noticed many of the principal local celebrities of the borough the deceased gentleman so long represented in Parliament.”