Pic-nics and politics: a grand day out as Chartists take to the Thames by paddle steamer, 1850

On Whit Tuesday 1850, hundreds of London Chartists crowded on to a paddle-steamer for an excursion to Gravesend, where there was fun and games to be had and speeches to be made. With good weather, and only a few stragglers left behind, the day was judged a great success.

After a few early drops of rain, the weather took a turn for the better, and by seven in the morning of Tuesday 21 May, ‘the sun shone forth in warm serenity’ on a small crowd of men, women and children who had gathered outside the National Charter Association’s offices. They were there for what had been billed as a combined excursion, demonstration and public meeting for the London Chartists. A steam packet had been hired for the day, and tickets sold. There would even be a brass band for entertainment on the voyage down the Thames to Gravesend, where fun and games were to be had alongside the more serious matter of ‘making the principles of Chartism known to the inhabitants of that Tory-ridden, parson-driven town’.

The NCA had made tickets widely available through those who usually sold the Chartist press across the capital: at a shilling and sixpence for adults, a shilling for children under fourteen, and free of charge for infants under three, this really was intended to be a family event. Tickets for the ‘excellent cold dinner, with pastry, &c’ were an extra shilling and sixpence per head, and demand was strong, those wanting to be part of the proposed grand day out being warned that they should buy their tickets early, ‘the number being limited’ (Reynolds’s Weekly Newspaper, 19 May 1850, p8).

When the day came, the mood among the ‘hundreds of good and true Democrats’ (Northern Star, 25 May 1851, p1) who had gathered at 14 Southampton Street, just off the Strand, was one of happy anticipation, and bright sunshine added to the gaiety of the day. As the reporter for Reynolds’s Weekly Newspaper (possibly George Reynolds himself) put it: ‘The smoke from 10,000 chimneys failed to dim its splendour, and, as we wended our way down the City-road, towards London-bridge, we felt assured that for one day, at least, the heavens would be propitious to the cause of the people’ (26 May 1850, p7). Better still, it was Whit Tuesday, so for some at least this would have been a heady third successive day free of paid labour.

‘A dense mass of human beings stood upon the pier’

Reynolds went on: ‘On arriving at [Adelaide] wharf, alongside which the steamer “Gem” was lying, an animated sight opened before us; men, women, and children were spread in straggling groups about the wharfs, awaiting the moment of embarkation, while a dense mass of human beings stood upon the pier in the immediate neighbourhood of the vessel, to take possession of the seats upon its deck. At length the word was given, and the living mass soon passed on board, filling every seat, from stem to stern, and crowding every convenient spot available for standing, while many sought the cabin, as a refuge from the sun, until the breeze should temper its scorching influence. A fair interval was allowed for the accommodation of late arrivals, and at five minutes to nine, as the military band on board struck up the “Marsellaise”, the vessel moved away from Nicholson’s Wharf amid the cheers of its living freight.’

He continued: ‘Steadily down the river moved the “Gem,” between the dense masses of shipping lining the shore on either side, while towering high above the tall-masted vessels rose huge piles of warehouses, the sight of which reminded the advocates of the rights of labour of the lion’s share of the national wealth now claimed and enjoyed by the non-producer. The Custom-House and the Tower presented due reflections to the minds of the democrats who looked upon them – the one emblematic of long ages of by-gone tyranny, the other the embodiment of an unjust and crushing system of taxation.’

The Northern Star which ran its account on the front page, reported that the Chartists found themselves ‘gliding down the pool, amidst a forest of masts, Walter Cox’s brass band playing the enlivening strains, “The days we went a Gypysing a long time ago” &c, ever and anon being recognised and greeted by some friendly tar, each pier adding to our numbers, until the Gem could take no more’ (26 May, p1). A third radical paper, the Weekly Dispatch, put the number on board at London Bridge at some 700 (26 May 1850. p5), and the additional stops at Tunnel Pier, Commercial Pier, Deptford, Greenwich, Blackwell and finally Greenwich must have added considerably to the numbers.

The Gem sped on, with passengers clamoring for a place on the paddle-boxes, from where the best views could be had, passing Erith, Purfleet, Greenhithe and Rotherhithe ‘at arrow-speed’, and reaching Town Pier at Gravesend at half past eleven.

‘A more respectable party had never visited Gravesend’

With the band safely ashore and ready to lead the way, wrote Reynolds, the rest of the passengers disembarked, ‘the company formed themselves in line, four deep, and when the whole were landed, headed by the Executive Committee, – namely Mr. Julian Harney, Mr. G.W.M. Reynolds, Mr. T. Brown, Mr. Stallwood, Mr. Milne, Mr. Miles, Mr. Grassby, and Mr. Arnott, the procession moved up the High-street to the sound of the Marsellaise, towards the cricket ground of the Bat and Ball Tavern, which had been hired for the occasion.’ The Marseillaise was a tune much in favour with Chartists, but neither Reynolds’s Weekly Newspaper nor the Northern Star quite grasped the spelling that day.

Gravesend was a popular destination for excursion parties, close enough to the capital for day-trippers but far enough down river to escape the city’s smoke and grime. Charles Dickens had set part of his latest novel, David Copperfield (published in serial form in 1849), in the town, and a few years later, he would buy a house at Gad’s Hill, just a couple of miles away. But the town ‘had not before been honoured by the celebration of a Chartist festival’ and the procession drew curious crowds who apparently agreed that ‘a more respectable and well-conducted party had never visited Gravesend’.

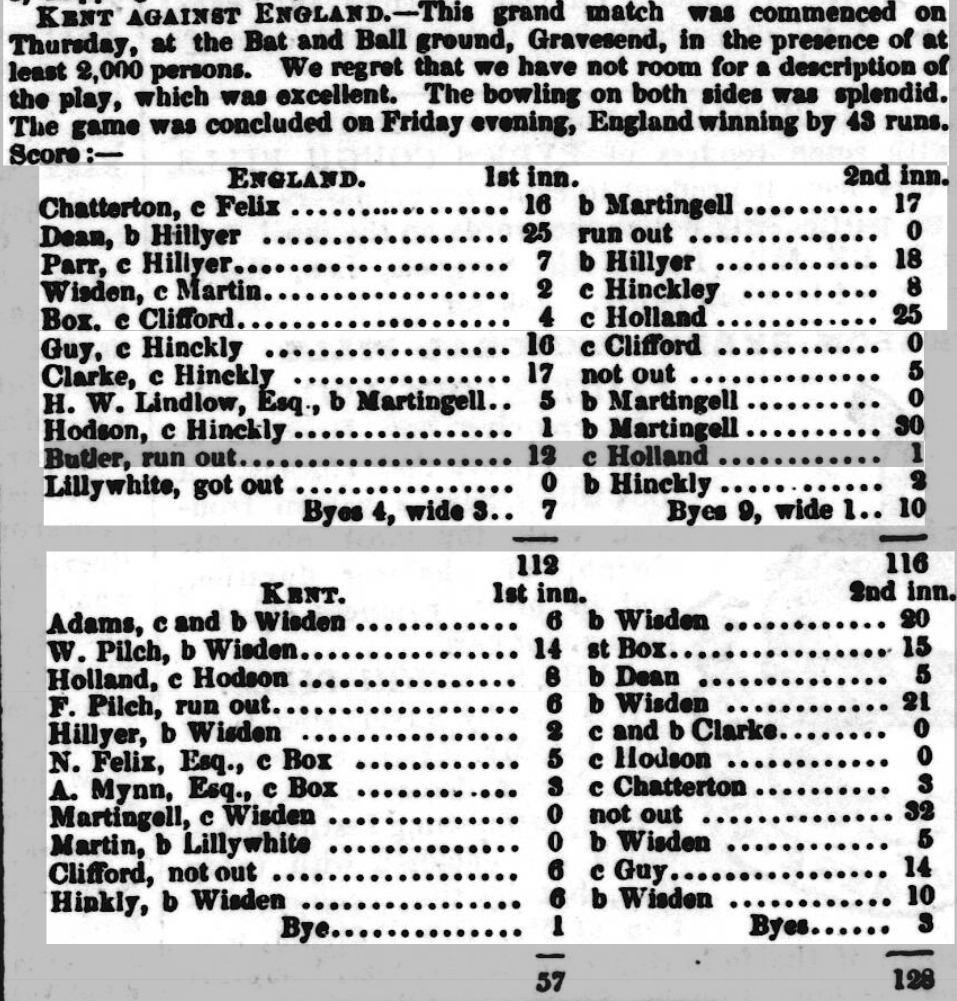

The tourists would not have far to go before they reached the Bat and Ball with its enclosed six-acre field. This was a major attraction, offering visitors somewhere to play ‘at cricket, trap-bat, quoits, archery, and other field sports’, and advertising, ‘Large or small Dinner or Tea Parties provided for on the shortest notice, and persons with their own refreshments accommodated’ (Morning Advertiser, 2 August 1853). In 1849, Kent County Cricket Club had used the ground for a match against an All England Eleven, and would continue to play first-class cricket there until 1971. The field is still there – attached to a now rebuilt Bat and Ball public house – and still used by Gravesend Cricket Club for its home matches.

Fun, games and a good dinner

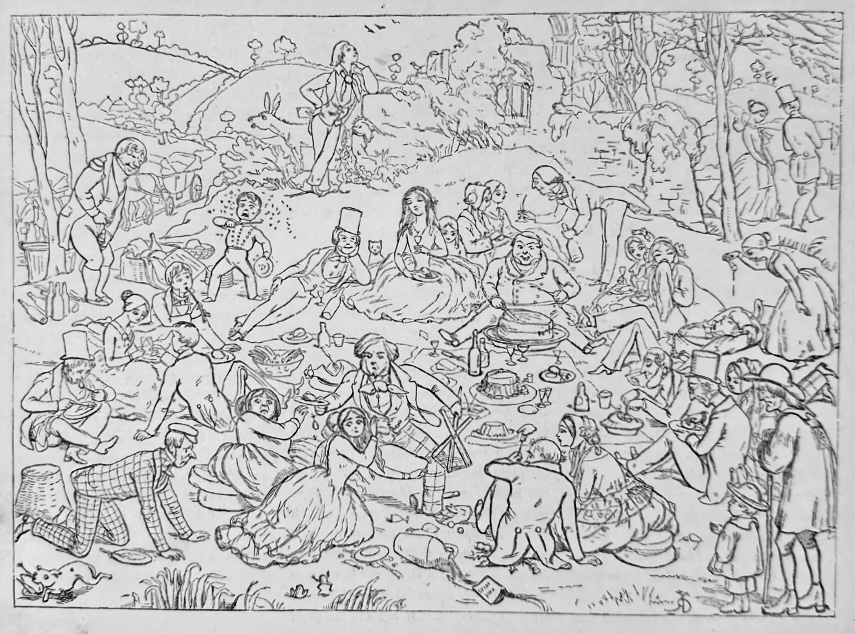

Having reached their destination, the assembled Chartists gave three cheers for the People’s Charter ‘and each looked for pleasure according to the banks of his individual inclinations. Some engaged in the right English game of cricket; Some wandered round the town in search of its lions; some ascended to the top of Windmill Hill, and feasted their eyes upon a far wider expanse of land and water than falls to the lot of Londoners to view, except on such occasions; some strolled along the green lanes, and listened to the warbling of the song-birds; while others and perhaps the majority of the party, reclined upon the grass under the green hedgerows of the cricket ground in a series of parties.’ The Northern Star added a short walk to admire the pleasure gardens at Rosherville or a game of baseball to the recreations on offer.

At one o’clock, ‘a large party’ (so, presumably, not all of those present – others must have declined the additional 1s 6d a head and brought sandwiches) sat down to dinner in a spacious room opening onto the cricket ground. Though Reynolds ‘declined to inflict upon our readers the bill of fare, as is usual upon more aristocratic occasions’, he assured readers that in quantity and quality the dinner was ‘most satisfactory’, and that ‘the tables, as they stood displayed before the guests sat down, presented a most pleasing appearance’.

After the tables were cleared, Thomas Brown, a member of the NCA Executive, sang the Marseillaise, ‘the whole audience joining in the chorus’, according to the Northern Star. ‘A collection was then made for the German and Polish refugees, and £1 10s., was collected, and handed over to Mr Langenschwarz for presentation to the Committee in Green Street, Soho. The waiters likewise learned that Chartists can be generous as well as just.’ Dinner over, ‘pleasure once again became the order of the day,’ Reynolds reported, ‘and in addition to the allurements of the morning, a spacious room was opened for the accommodation of dancing, and for an hour a large party tripped it on the light fantastic toe.’

Time for speeches

By now, the Londoners had been joined by rail, boat and road by ‘a large acquisition of democratic strength from Rochester, Stroud, Chatham, Sheerness, Tunbridge, Tunbridge-wells, Greenwich, Woolwich, Maidstone, &c &c’, and it was time for the serious business of the day to begin. ‘The dancing had ceased, the pic-nic parties had rallied to the common centre, Windmill Hill and the green lanes gave back their wanderers, and the aspect of the scene was imposing in the extreme. Rochester, Tonbridge, Tonbridge Wells, Sheerness, Maidstone, and other large towns had sent a portion of their inhabitants to attend the Chartist gathering; while the villages in the more immediate neighbourhood of the spot were well represented. The number present was stated to be as high as 10,000; But probably 8,000 or 8,500 would be nearer the exact truth.’

At 3pm, John Randall, a local Chartist, was called to the chair amidst loud cheers, and the speeches began. George Reynolds moved a resolution in support of the Charter and spoke at some length. George Julian Harney seconded, once again with a speech. William Davis, a member of the NCA executive committee, then came forward to speak, followed by George Shell, who told the crowd that this was the first time he had addressed his brother democrats since 1848, and as a result of that he had spent the past twenty months in prison. The resolution was then passed unanimously, and votes of thanks given to the chair. The Northern Star reported: ‘Three cheers, loud and long, were then given for the charter, and the meeting being at an end, the people betook themselves to their amusements until six o’clock, when the trumpet sounded, and the procession was formed, and walked in the same order as on coming, through the town down to the pier; the work of embarkation went rapidly on until half-past six, when the “Gem” left Gravesend.’ The Weekly Dispatch commented that ‘to the credit of the excursionists, it must be observed, that there was not a single instance of intoxication or disorderly conduct of any kind’.

A grand day out (for almost everyone)

Reynolds’s report, however, suggests that things did not go quite as smoothly as that might suggest, reporting that ‘as the hour drew near, groups of holiday-making Chartists thronged towards the pier until it became crowded. The vessel came alongside, and its deck soon filled; but unfortunately a few laggards were left behind, although in sight when the paddles were set in motion. Some stringent resolution of the pier, we are informed, necessitated this peremptory departure; yet we think that five minutes’ grace might have been accorded, instead of the three minutes only which elapsed between the time announced and the actual departure of the vessel.’

A few passengers light, the steamer made its way back up the Thames, dropping some off at their original departure points along the way. ‘On arriving at Greenwich pier, about fifty persons alighted, and a band from the shore saluted us with the “Marseillaise,” which was responded to by Cox’s brass band on board, amidst the most hearty cheering for the People’s Charter,’ declared the Northern Star. ‘The merry song was now kept up until fresh water pier was again reached, where the passengers safely landed, all having enjoyed a rich treat.’

Reynolds reported that, ‘With the exception of the inconvenience arising to a few from this extreme punctuality, nothing we believe, but pleasurable reminiscences are connected with the Chartist excursion to Gravesend of the Whitsuntide holidays of 1850.’ The Weekly Dispatch judged: ‘This is regarded by the Chartists as one of the most important demonstrations they have made since the memorable Kennington-common affair in April 1848.’