William Hill, 1806 – 1867

William Hill edited the Northern Star from its launch in 1837 until 1843, when he was sacked by its owner, Feargus O’Connor. But his private life became a public scandal in the pages of the paper’s rivals in Leeds.

In his near-contemporary history of the Chartist movement, Robert Gammage summed up William Hill as ‘an accurate and clever but not a very agreeable writer’. Had Hill not still been very much alive when the first edition of the book appeared in 1854, Gammage might well have added that Hill was also not a very agreeable man. As editor of the Northern Star from its launch in 1837 until 1843, he was, however, a central figure in the Chartist movement.

William Hill grew up in Barnsley, where his father John was a handloom weaver. Though William was born at Gainsborough in Lincolnshire, the youngest of four children, the family had moved to Yorkshire in search of work when he was still ‘a baby in arms’, as a long-serving editor of the Barnsley Chronicle, who must have known him personally, wrote in 18801.

The family found a home at 23 John Street, a three-storey brick building ‘located in one of the most unclassic districts of the town, the lower portion being used as a huckster’s shop’.2 Hill was ‘put to the loom’ at an early age, but apparently found that the work was ‘not congenial to him and he soon forsook it, vowing that he would never set foot on treadle again as long as he lived’. At the age of eighteen, he married and left Barnsley. For a time, Hill ran a school on the outskirts of Huddersfield, where he may first have met Joshua Hobson, later the publisher and printer of the Northern Star, but who in 1833 launched his own radical paper, the Voice of the West Riding.

Hill became involved with the New Church, a dissenting sect based on the teachings of the eighteenth century theologian Emanuel Swedenborg. A 1905 account of Hill’s life in the Swedenborgian New-Church Magazine, which draws on church records, notes Hill’s presence at the 1836 General Conference of the church in Manchester at which he represented a short-lived society of just fourteen members then meeting at the Tabernacle in Bowling Lane, Bradford.

The minutes of the following year’s conference noted: ‘From Bradford – The leader of the Society which existed in this place having gone to preside over the society at Hull, the members no longer meet together for worship.’ Hill’s new Hull society met at 5 Dagger Lane, which had been a Congregational chapel since the 1690s but had become a Swedenborgian meeting place in the early 1830s. Though it seems unlikely that Hill’s new congregation was large enough to give him much of a living, it evidently provided accommodation, as a directory published in 1838 records this as his home. This may also have been where Hill’s wife Hannah, ‘a lady of considerable educational achievements’ first opened and ran a school – which must have helped the family finances.

Editor of the Northern Star

During the early autumn of 1837, when Feargus O’Connor was planning his Northern Star (not yet a Chartist newspaper as the Charter itself did not exist until 1838), Hobson introduced him to Hill and recommended him as editor. Though having little if any newspaper experience, the Rev William Hill, as he was now styling himself, accepted O’Connor’s offer of the job and set to work.

Under Hill’s editorial leadership, the paper’s circulation rose from 3,000 when it was launched to a peak of 50,000 the following year. Gammage wrote disparagingly that the paper’s success was due not to Hill’s editorship but to O’Connor’s own popularity and to the fact that it provided the movement’s most complete record. ‘There was not a meeting held in any part of the country, in however a remote a spot, that was not reported in its columns, accompanied by all the flourishes calculated to excite an interest in the reader’s mind, and to inflate the vanity of the speakers by the honorable mention of their names. Even if they had never mounted the platform before, the speeches were described and reported as eloquent, argumentative and the like; and were dressed up with as much care as though they were parliamentary harangues fashioned to the columns of the daily press.’ All of which, despite Gammage’s condescension, certainly sounds like the actions of a clever and effective editor.

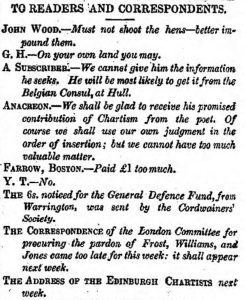

Hill divided his time between the family home, now in Templar’s Street in Hull, and a house in Market Street, Leeds, which was convenient for his work at the Northern Star. As editor, Hill wrote a sometimes abrupt column titled ‘To Readers and Correspondents’ in which he answered readers’ questions, issued short announcements, rejected poems that were not up to standard, and ticked off contributors for failing to get their reports in on time. The column was occasionally tantalizingly opaque: ‘Alfred Green. – We cannot interfere in the disputes between the Bingley and Keighley cricket players’ (NS, 15 September 1838, p4).

He also wrote longer leader articles on topics of the day. But as John Widdop, a former Chartist weaver from Barnsley, later recalled: ‘Hill was not by any means a lively writer, his articles being long and heavy. At times smart, sensible, lively articles would appear, and these, it was said, were from the pen of his wife.’

A scandal in the chapel

Alas, their married life proved to be a less successful collaboration, their separation becoming both acrimonious and very public with a little help from the Northern Star’s Whig competitor, the Leeds Mercury. Under the headline ‘Practical effects of socialist principles’, the rival paper reported that Leeds Workhouse Board had spent the previous two weeks ‘occupied with the case of Mrs Hill, the wife of Mr Wm Hill, who writes himself the Reverend Wm Hill, and who is the minister of a Swedenborgian-Socialist Chapel at Hull, and editor of the Northern Star’ (Leeds Mercury, 24 April 1842, p5).

It claimed that after seventeen years of marriage and two children (there seem, in fact, to have been three), Hill had deserted his wife, and vindicated his conduct to his congregation on the principles of Robert Owen, ‘alleging that his wife’s temper was bad, and that, having lost regard for her, he could not continue to live with her, without being guilty of legalized adultery!’ For a while, Hill had given his wife a weekly allowance, ‘but not liking to continue this, he wrote to Mr Mason, the Relieving Officer, desiring him to relieve her at the Workhouse.’

After Hannah Hill put her case to the workhouse board, the relieving officer called on William and persuaded him to reinstate his payment of 10 shillings a week. ‘The Swedenborgian congregation at Hull have nearly all deserted Hill, and their place is now supplied with Socialists and Chartists,’ the Mercury concluded.

Hill might have been wise to leave matters there. But the following week, the Mercury received a lengthy letter in Hill’s defence from James Bolingbroke, who signed himself ‘Senior Deacon of the Christian Church, worshipping under the Pastoral Care of the Rev. William Hill at Hull.’ The paper printed it in full, noting that it was ‘from beginning to end written by Hill himself; it is in his own handwriting, and it is undoubtedly his own composition’.

Bolingbroke’s letter indignantly rebutted the suggestion that the church had any connection to socialism, but singularly failed to deny the allegation that, having left his wife, Hill had left her and his children reliant on parish relief until forced by the relieving officer to pay up. It claimed that after putting his side of the story to his congregation, and in the absence of Mrs Hill, who had declined to attend and had made allegations ‘impugning the moral character of our beloved and esteemed minister’, the church had exonerated him. Finally, it reported that the congregation had passed a resolution condemning Hannah Hill for conducting herself ‘in a manner utterly at variance with the truth and sincerity of the Christian character’, and demanding that in front of witnesses she sign a statement drawn up by William Hill recanting all allegations and apologizing to Hill and others.

A furious Hannah Hill replied in print: ‘He tells me that I am mistress of my own actions, that I am at liberty to make any engagement that I may like, to get a fresh husband if I choose, and that the connection between us is now dissolved for ever, and we are to each other as though we had never been. I suppose he openly wishes to do the same, when at a church meeting my husband was outraging all the common decency of the females, especially of his church, by giving this reason for putting me away’ (Leeds Mercury, 15 May 1841). She revealed that the recantation she was told to sign referred to claims she had made about her husband’s ‘criminal and adulterous connection and intercourse’ with five named women members of the church. And she claimed that among the allegations of unreasonable behavior made by William was ‘that I found fault and was jealous, because he took Mrs Wallworth to Grimsby, Cleathorpes, and Barton, and several other places’.

Not surprisingly, the couple were not reconciled, and little of this found its way into the pages of the Northern Star. The census taken on 6 June 1841 finds Hannah at an address in Edwards Place, Albion Building, Hull with her three children, Elizabeth, Hannah and William. The older William Hill is not there.

A break with O’Connor

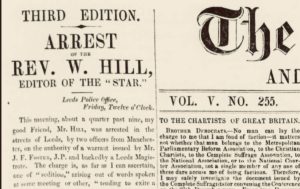

As editor, Hill attempted to maintain some distance from the paper’s proprietor. When Feargus O’Connor condemned as divisive the call for Chartists to abjure alcohol, Hill wrote a leader urging Chartists to ‘have the courage and conquer their own vices’ (NS, 28 November 1840), and put his name to Henry Vincent’s teetotal address (English Chartist Circular and Temperance Record for England and Wales, Dec 1840). In the summer of 1842, though, the two men were united in rejecting calls for the National Charter Association, then in conference in Manchester, to back the great strike wave then sweeping the North. It saved neither man from arrest (Hill was taken by police outside the Northern Star office in Briggate); both were tried and found guilty at Lancaster assizes, but never sentenced.

As divisions between the two men widened, O’Connor finally sacked Hill in July 1843. Hill’s initial response was to launch a new periodical, called the Lifeboat, in which to publish anti-O’Connor views. He also promised a ‘History of the Rise and Progress of the Chartist Agitation’, but it never appeared, and the Lifeboat sank in January 1844 after just two months.3 Hill moved to Edinburgh in 1848, and for a short time edited the Chartist North British Express, but he had more success establishing a trade protection society, which published weekly lists of bankruptcies to alert other businesses. By the early 1850s, the society also had offices in London, Dublin and elsewhere.

Having sold his successful business to a competitor, Hill returned to Hull, where in 1863 he became proprietor of the Hull Daily Express, before selling it on and starting the short-lived Hull Reflector and Local Correspondent. With his health and eyesight failing, Hill went into retirement. In May 1867, he suffered a stroke that left him paralysed on his right side. Eight days later on Friday 17 May he died at his home, 2 Wilberforce Road, Hull. He was buried in an unmarked grave at Springbank Cemetery the following Wednesday.

Notes and sources

1. ‘The Rev. William Hill’, Barnsley Chronicle, 29 May 1880 p.4. Accessed via the British Newspaper Archive (24 January 2024).Though unsigned, this account of Hill’s life was ascribed by Charles Higham in The New-Church Magazine (see below) to the Chronicle’s former editor, Alexander Paterson, ‘who was for thirty-four years prior to 1899 editor of the journal in question.

2. ‘The Rev. William Hill. New-Churchman and Chartist. Some Biographical fragments’, by Charles Higham, The New-Church Magazine, vol. XXIV, no. 283, July 1905.

3. ‘Hill, William (Reverend) (1806-1867)’ by Stephen Roberts in Dictionary of Labour Biography Volume XV, edited by Keith Gildart and David Howell (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

See also: History of the Chartist Movement 1837-1854 by R.G. Gammage, originally published in 1854, with a revised second edition in 1894, and reprinted with an introduction by John Saville by Augustus M. Kelley in 1969.