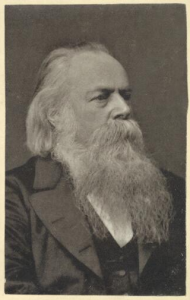

Henry Vincent, 1813 – 1878

Henry Vincent was, by many accounts, the most effective public speaker in the Chartist movement. His talent won him a substantial personal following; but after it also earned him two years in gaol, he abandoned his early radicalism for a life on the lecture circuit.

Born on 10 May 1813, Henry Vincent was the eldest son of Thomas Vincent, a comfortably off silver and goldsmith, whose own father, also Henry, had made horse bits, spurs and harnesses for the Prince of Wales (later George IV)1. The young Henry Vincent spent his early years at the family home at 145 High Holborn, ‘And it is said that he trundled his hoop in childhood in Red Lion and Russell Squares, near to his birthplace, and that prosperity and happiness were the portion of the family at that time.’2

But when Vincent was eight years old, his father’s business failed. The family relocated to Hull, but within a year, Thomas Vincent, who had found work in the port town as a customs officer, had been admitted to Sculcoates Refuge for the Insane, and died, leaving his wife Anna to bring up her four surviving children alone.

At fourteen, Vincent was apprenticed to a printer. Enthused by the revolution of 1830 in France, he also became involved in the radical life of Hull, joining the town’s political union and advocating for universal suffrage at the time of the Reform Bill crisis in 1831-32.

Radicalism and a return to London

Completing his apprenticeship, and able to seek work as a journeyman compositor, Vincent returned to London with his mother and younger sister and brothers in 1833. Here he joined the London Union of Compositors, and worked for a time at the well known firm of Spottiswoode, but left along with sixty others after a strike over union recognition in 1836. At about this time, he also came into contact with William Lovett, and in November 1836 joined the London Working Men’s Association.

Though still in his early 20s, Vincent was one of the six working men charged with elaborating the six points of the LWMA’s political programme into a Parliamentary Bill (along with Henry Hetherington, John Cleave, James Watson, Richard Moore and William Lovett). The LWMA recognised Vincent’s talents as a public speaker, and in the summer of 1837 he and the older, more established radical speaker and newspaperman Cleave were sent to Yorkshire as ‘missionaries’ (or, as the London Despatch put it, ‘working men’s apostles’, [13 August 1837]). Ahead of the publication of the People’s Charter, their task was to establish working men’s associations.

Cleave and Vincent opened their campaign at the New Victoria Rooms in Hull, where, as the True Sun reported: ‘The hall was crowded to overflowing. The gallery was also well filled with ladies’ (24 August, 1837). With Vincent’s rhetoric whipping up the crowd, and Cleave setting out the radical programme and plan of action, the two quickly established an effective partnership, leaving behind them working men’s associations both in Hull, Leeds and other towns when they returned to London.

Appeal to ‘the fair sex’

Vincent was hugely popular, not least among the substantial numbers of women who crowded in to hear him speak. The historian R.G. Gammage, who, at the age of just eighteen years old, heard Vincent speak in 1838, would recall decades later:3

‘At that time he was in the prime of youthful vigour, being but twenty-five years of age. In stature, Vincent was the very opposite of his coadjutor Lovett. The latter was of a tall, commanding figure, while the former was much below the middle size. His person, however, was extremely graceful, and he appeared on the platform to considerable advantage. With a fine mellow flexible voice, a florid complexion, and, excepting in intervals of passion, a most winning expression he had only to present himself in order to win all hearts over to this side. His attitude was perhaps the most easy and graceful of any poplar orator of the time… With the fair sex, his slight handsome figure, the merry twinkle of his eye, his incomparable mimicry, his passionate bursts of enthusiasm, the rich music of his voice, and, above all, his appeals for the elevation of woman, rendered him an universal favourite, and the Democrats of both sexes regarded him as the young Demosthenes of English Democracy.’

It would appear that Vincent made the most of his popularity, both in London and on tour. Between 1837 and 1852, Vincent wrote regularly to his cousin John Minikin, and it is clear from the surviving texts that he thrived on the attention of young women keen to make the acquaintance of this exotic arrival in their town. And either in his head or in his bed, Vincent enjoyed his time alone with them.4 In one letter to Minikin from Halifax and dated 26 August 1838, Vincent can barely contain his boast:

‘Monday Morning – I was obliged to give up writing yesterday in consequence of a piece of green silk and a pair of piercing eyes kindly volunteering to walk out with me over the beautiful hills that surround this delightful little town – How would I refuse such kindness?’

Speaker and newspaper editor

Vincent and Cleave returned to London at the end of their tour having held successful meetings at Bradford, Halifax and Huddersfield, and with working men’s associations up and running at Hull, Leeds, Gommersall and Almondbury. After the People’s Charter was finally published in May 1838, the LWMA would turn again to Vincent to take its message to the country, with a series of speaking tours that took him that year to Scotland, the North of England, the Midlands, the South West, and South Wales.

Small wonder that when in September 1838, the newly minted Chartists met at Palace Yard, Vincent was one of the main speakers. In the showdown between the LWMA and rival London Democratic Association for places at what would be the first Chartist convention, Vincent with the backing of the LWMA was elected one of the London delegates, while his near-contemporary George Julian Harney of the LDA was defeated.

As the year came to an end, Vincent increasingly turned his attentions to the South West. There, in February 1839 he launched his own unstamped four-page Western Vindicator, based in Bristol but able to appeal to a large readership in the South West, West Midlands and in South Wales. Vincent clearly drew on his own experience as a compositor and on the expertise of Cleave and other veterans of the unstamped press, creating a network of radical printers, publishers and vendors across the region to make a success of this new venture. By August of that year, the paper was selling 3,400 copies a week (200 of them through Cleave in London), and was in profit.5,6

Vincent also redoubled his efforts as a speaker, travelling throughout the paper’s circulation area and holding meetings in the face of opposition from local magistrates and employers. At Devizes in Wiltshire, efforts were made in advance to halt the Chartist meeting, and special constables and lancers deployed in the streets. When Vincent and his supporters persisted, a drunken mob brought in from the surrounding villages to reinforce local opposition attacked the platform party with bludgeons and broke up the meeting. Bruised and shaken, Vincent and his party, among them the Bath solicitor William Prowting Roberts, made it to safety in the Curriers’ Arms, but then had to be escorted out of town by the High Sheriff and his forces. As Vincent recalled: ‘I may just state that had it not been for the very laudable and Christian conduct of a few of the Tories, that myself and Roberts would have been killed.’ Vincent duly recorded this and other of his travels in the Vindicator.7

Newport and prison

Vincent’s visits to Newport, however, were to prove more momentous. There, on 19 April 1839, he spoke to a crowd of more than 5,000 supporters – despite warnings that there were ‘gentlemen’ in the meeting who were preparing to fire on him. Though the meeting had been declared illegal, Vincent may have thought nothing more of his speech here than of those he had made on so many other occasions. The magistrates, however, thought differently. They issued a warrant for his arrest, and on 7 May, following his return to London to take part in the Convention, he was arrested on his own doorstep at midnight. Brought back to Newport, he was unable to raise the sureties demanded of him, and was instead committed to Monmouth Prison.

Although Vincent would later be released on bail, his taste of freedom was brief. Tried at the town’s assizes in August, he was sentenced to a year in prison. While in gaol, Vincent continued to write for the Vindicator, to the dismay of the authorities, but in December of that year he was forced to cease publication. The fact that Vincent was in prison at the time meant that he escaped the fate of his friend John Frost, who was transported to Australia after the Newport rising. Vindictively, however, he was again put on trial in March 1840 for conspiring with Frost, and sentenced to a further year of incarceration.

Vincent had been treated relatively well in Monmouth, but now he was transferred to the far harsher regime of Millbank Prison in London. Vincent’s friends and political allies launched a campaign to have him moved. Following an intervention on his behalf by Sergeant Talfourd, the prosecuting barrister at both trials who was also a serving MP, Vincent was transferred after a month to the less punishing surroundings of Oakham Gaol.

A new life, and a new career

While serving out the remaining seven months of his sentence, Vincent came under the moderating influence of Francis Place, reportedly telling him that he was determined ‘not to remain the fool I am. My desire is to learn’. Though still behind bars, he now welcomed the development of Christian Chartism in Scotland, and began his strong advocacy of teetotalism.

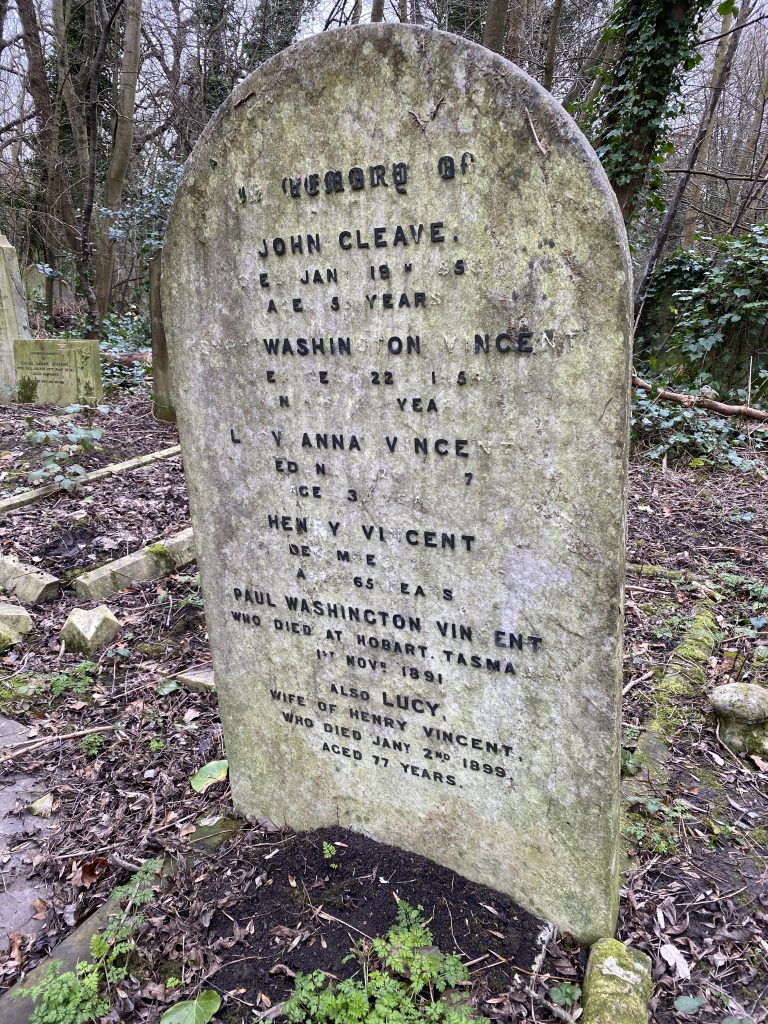

In January 1841, Vincent began a completely new life. Within a month of his release from prison, he married 19-year-old Lucy Cleave, some nine years his junior and the daughter of his friend and mentor John Cleave, at Chelsea Register Office. As she would tell William Dorling, his biographer, after her husband’s death in 1879, ‘She had known Vincent for some time as a frequent visitor at her father’s house, and had learnt to love him; although until after he had left prison she had not been engaged to become his wife.’

But for what must have been a whirlwind few weeks that January, Lucy would not have seen Henry in person for the previous two years. But the marriage may also have been something of an escape for her from unhappy home circumstances. The previous year, John Cleave had moved his mistress into the family home, to the great dismay of his wife, Mary Ann. Despite this, according to Dorling, ‘Mr Cleave was taken by surprise, and at first was slightly annoyed that a love match had come to pass.’

The couple moved to Bath, where Vincent resumed publication of what was now to be the National Vindicator, which he co-edited with Robert Kemp Philp, set out again on his political travels, and in the spring of 1841 put himself forward as a candidate at a parliamentary by-election in Banbury. Francis Place was outraged, telling him that he faced certain defeat and that even in the unlikely event he won, he would be unable to support himself (the job of MP being unpaid). He instructed Vincent to ‘leave off running about the country, your wife with you, learning nothing that can be of any use to either of you, but much which is likely to tell in the contrary direction. Go to your own business and become a man of business for the next ten years. You may perhaps at the end of that time be in a condition to do some public service.’8

Condescending though he invariably was, Place was correct on this occasion and Vincent was heavily defeated at Banbury. Meanwhile, Vincent’s politics were mellowing while his religious sensibilities were growing. The Vindicator was no longer the commercial success it had been in its early days and was soon closed down. Politically, Vincent and Philp shifted their allegiance to Joseph Sturge’s Complete Suffrage Union, while maintaining that there was no contradiction between this and the Charter. And he began to carve out for himself a new and less dangerous career.

Realising that his spectacular oratory could serve another purpose, he began to lecture on a wide range of topics, from the English Commonwealth and civil wars to temperance, and from Ancient Rome to the Great Exhibition and ‘the philosophy of true manliness’. As his entry in the Biographical Dictionary of Modern British Radicals notes: ‘As always with Vincent, the style and the performance were more important than the logical content.’ Vincent had tapped into a demand for education and self help that would ensure him a steady living, and in the 1860s and 1870s lead to financially lucrative tours of the United States. Though Vincent never made a fortune, his lecturing career meant that the family were comfortably off: the 1861 census shows that they were able to afford three live-in servants (a cook, a nurse and a housemaid) at their home address at 9 Mornington Crescent.

Vincent never again played any significant part in British politics – though he would remain a consistent supporter of the principles of the Charter throughout his life, and on a number of occasions unsuccessfully contested parliamentary elections as an independent liberal. Successive census entries for the growing Vincent family (there would be six children), list Henry as a ‘lecturer in historical and science subjects’ and as a ‘literateur and lecturer’, while in 1851 Lucy would declare her own occupation as ‘wife of Henry Vincent’.

Memories of the ‘dark days of ’38’

At the end of November 1878, Vincent sent off on his last lecture tour. His health now failing, he returned to London ten days later and took to his bed. There, at his home at 74 Gaisford Street in Kentish Town, with his family around him, on 29 December 1878, Henry Vincent died.

Vincent was buried at Abney Park Cemetery on 2 January 1879. ‘The woman who had been his loving companion for nearly thirty-eight years, stood at his grave accompanied by some of his children.’ But they were not alone. Vincent’s death was widely reported, and many joined the family at the graveside.

The Daily News (3 January, 1879), reported: ‘The day was bright and fine, but bitterly cold, the frozen snow lying everywhere upon the grass and paths. An unusual number of ladies, however, were present, among whom many were distinguishable as belonging to the Society of Friends by the quaint, old-fashioned costumes still to be seen in the neighbourhood of Stamford Hill, though now almost a thing of the past. Mingled with the little groups that lingered after the mourners had departed were some old Chartist friends of the deceased, now grey and bent with years, who were to be known by their talk of the dark days of ’38 and the providential escapes that Mr Vincent had experienced from the fury of ‘”Tory mobs” in towns where, as was observed, in later and happier times, he had received as a public speaker, a respectful and affectionate welcome.’

The final word, however, should go to Lucy Vincent, who in her foreword to Dorling’s biography, wrote: ‘In tracing the course of my husband’s eventful life, I feel more proud of his utterances in early days, which alarmed timid people and sent him into unjust punishment, than I am of the expressions of his matured intellectual power. I reverence and cherish the memory of the indomitable courage which made him dare to resist oppression when resistance was dangerous and Nonconformity unfashionable both in religion and politics. The “strong language” was a necessity of the time, and few things have pained me more than the apologetic way in which even friends have spoken of it.’

Sources and further reading

1. Family information from Henry Vincent (1813 – 1878) on Wikitree. Accessed on 5 August 2023.

2. Henry Vincent: A Biographical Sketch, by William Dorling, with a preface by Mrs Vincent (James Clarke and Co, 1879). Accessed on 5 August 2023 on Trove (National Library of Australia).

3. History of the Chartist Movement 1837-1854, by R. G. Gammage (second edition, 1894). Reprints of Modern Classics (Augustus M. Kelley, 1969)

4. ‘Humour, Satire and Sexuality in the Culture of Early Chartism’, by Tom Scriven in The Historical Journal (Cambridge University Press 57:1, 2014). Accessed on 21 August 2023.

5. ‘The Western Vindicator and Early Chartism’, by Owen R. Ashton in Papers for the People: A Study of the Chartist Press, edited by Joan Allen and Owen R. Ashton (Merlin Oress, 2005).

6. Copies of the Western Vindicator from July to December 1839 have been digitised and are on open access at People’s Collection Wales.

7. Vincent’s ‘Life and Rambles’ articles have been digitised and are on open access on the Vision of Britain website.

8. The Life of Francis Place, 1771-1854, by Graham Wallas (Longmans, Green & Co, 1898). Accessed on 29 August, 2023 on the Internet Archive.

‘Vincent, Henry (1813-78)’ by Brian Harrison, Dictionary of Labour Biography, vol 1 (Macmillan, 1972).

‘Vincent, Henry (1813-1878)’ by David J. Wrench, Dictionary of Radical Biography, vol II, 1830-1870 (Harvester Press, 1984).

I visited Henry Vincent’s grave in February 2024 and wrote about it for the Chartist Ancestors blog – see Greetings from Abney Park.