MPs vote to ignore the 1842 leviathan petition

In May 1842, MPs were asked to allow a few of the Chartist petitioners who had brought the leviathan petition to Parliament to address the House of Commons, as others had been in the past. The request was rejected by a massive majority. The debate is reported here.

This is one of a number of articles dealing with the leviathan petition. See also:

Organising the 1842 petition

The 1842 Chartist Convention

Presenting the 1842 petition

Engraving to mark the petition

The 1842 petition in numbers

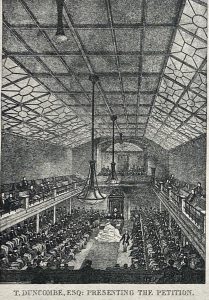

Signed by no fewer than 3,317,752 men, women and, in some cases children, the 1842 petition really was the ‘leviathan’ reported by sympathetic newspapers. At more than six miles long and so heavy that in needed thirty men to carry it, the petition would not at first fit through the doors of the House of Commons. With the door jambs removed, Feargus O’Connor and others who had brought the petition to Westminster still had to take the vast river of paper apart so that it could be carried in. And even then, as Hansard noted: ‘When unrolled, it spread over a great part of the floor, and rose above the level of the Table.’

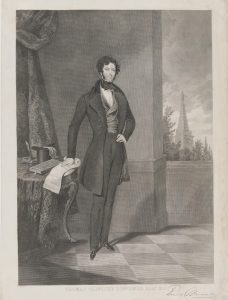

On Monday 2 May, Thomas Slingsby Duncombe, the radical aristocrat MP for Finsbury who had already proved to be the Chartist movement’s most reliable friend in the House of Commons, spoke only briefly once the petition had been brought into the Chamber. The case he wanted to make was that MPs should invite some of the petitioners to speak at the bar of the House in support of the petition. But this would have to wait until the following day.

For now, however, he was content to list the number of signatures collected in towns and cities up and down the country, adding further to the impact of the vast size of the petition, and surely making even the most hostile of MPs think twice if so many of their own constituents had put their names to it – though for obvious reasons, the signatories were not necessarily in a position to eject them from the House at the next election as so few qualified for the vote.

Duncombe told the House: The list of hamlets and towns from which less than 10,000 signatures were procured, is so very long, that I will not detain the House by reading it. I will name those towns only from which more than 10,000 have been obtained. They are these: Manchester, 99,680; Newcastle and districts, 92,000; Glasgow and Lanarkshire, 78,062; Halifax, 36,400; Nottingham, 40,000; Leeds, 41,000; Birmingham, 43,000; Norwich, 21,560; Bolton, 18,500; Leicester, 18,000; Rochdale, 19,600; Loughborough and districts, 10,000; Salford, 19,600; East Riding, Yorkshire, agricultural districts, 14,840; Worcester, 10,000; Merthyr Tydvil and districts, 13,900; Aberdeen, 17,600; Keithly, 11,000; Brighton, 12,700; Bristol, 12,800; Huddersfield, 23,180; Sheffield, 27,200; Scotland, West Midland districts, 18,000; Dunfermline, 16,000; Cheltenham, 10,400; Liverpool, 23,000; Staley. bridge and districts, 10,000; Stockport, 14,000; Macclesfield and suburbs, 10,000; North Lancashire, 52,000; Oldham, 15,000; Ashton, 14,200; Bradford and district, Yorkshire, 45,100; Burnley, and district, 14,000; Preston and district, 24,000; Wigan, 10,000; London and suburbs, 200,000; from 371 other towns, villages, &c.2,154,807—Total, 3,315,752.’

And he added: ‘I believe these to be every one of them bona fide signatures.’

With that, the Clerk of the House, whose table the petition had swamped, was required to read out, in full, the text of the petition.

The debate on 3 May 1842: Thomas Slingsby Duncombe speaks

The following day, Thomas Slingsby Duncombe was able to speak to the motion he had earlier put before the House. Rather than asking MPs to agree to the petition’s demands, this asked only that some of the petitioners should be allowed to put their case from the bar of the House of Commons.

In what is still a powerful speech to read, Duncombe began by thanking MPs on behalf of the Chartist Convention for the ‘kind and respectful manner’ in which they had received the petition. He moved swiftly on to remind MPs that nearly 3,500,000 people had signed it, and immediately addressed the issue of signatures from women and those aged under the voting age of 21, noting that ‘they were not, however, wholly the signatures of the male adult labouring population of the country. There were the signatures of a considerable portion of the wives of the industrious classes, and the petition contained also the signatures of several hundreds of the youth belonging to the same classes. But though this is so, yet I am prepared to prove, if required, that there are above one million of families of the industrious classes subscribers to that petition.’

Aware that opponents of the Charter would argue that petitioners could not be heard at the bar of the House, he cited precedents from the 1780s onward to show that they could. And he told MPs: ‘I desire you not to decide upon the merits of that petition, but I request you to listen to the grievances which the petitioners are prepared to state at the bar of your House. They will not only prove to you that a state of great distress exists in this country, but they will also prove, if not to the satisfaction of every man in this House, at least to the conviction of every unprejudiced mind, that those grievances arise from the neglect and misrepresentation of their interests within these walls. They will also state to you what they believe to be the remedy for the evils of which they complain. It will not be for you to decide tonight upon the merits of the remedy they may suggest; that will be for your consideration after having heard their statements. After you shall have heard their arguments, then it will be my duty to propose what I conceive would remedy and correct the abuses and mismanagement under which this country is now labouring.’

Turning to the history of constitutional reform, Duncombe went on: ‘The first time that this country seriously took up what was then called radical reform was in 1777. You will be pleased to observe, that this very subject has undergone all sorts of names, but they all resolve themselves into the same thing.’ When in the late eighteenth century Major John Cartwright had advocated universal suffrage, he had been called a ‘radical’; when the Whigs had taken up the cause, they had been called ‘Reformers’; ‘and now, those who were originally called Radicals, and afterwards Reformers, are called Chartists; but if you will examine the points upon which they stand, and the principles they advocate, these Chartists, in fact, are only the Radicals of former days.’

Duncombe pointed out that the substance of the six points embodied in the People’s Charter had been supported in earlier days by many of the great names of Whig politics, but that ‘a corrupt government, and a still more corrupt House of Commons’ had suppressed all dissent. ‘From 1829 to 1830, I need not remind the House of the state the country was in, when the Tory Government of that day were obliged to abandon the helm of Government. I need not remind you, that in consequence of the declaration of the Duke of Wellington against all reform, the Sovereign was not able to partake of the hospitality which the citizens of London offered, because his Ministers were so unpopular. I need not remind you of the disturbances, the scenes of riot, and the acts of incendiarism which took place in Kent at that period. The Government was changed, and the Whigs came into office. The first step they took in the following year was to introduce the Reform Bill.’

Those who had framed the Bill had been sincere, Duncombe said, adding, ‘They have been grievously —I will not say deceived, but disappointed—disappointed to the utmost extent of their hopes.’ At the general election of 1834, the people were prevented from voting, and difficulties were thrown in their way. And turning his attention to the Whig benches, he went on: ‘What has been the consequence? That there now exists a general dissatisfaction and discontent with the Reform Act. Nobody thanks you for it: on the contrary, everybody believes, though everybody may not say, that this House is more corrupt, more dishonest, and more disposed to what is called class-legislation, than even the notoriously and avowedly venal House of Commons as it existed before the passing of the Reform Act.’

Duncombe told MPs that he did not believe either the government or they were fully aware of the state of mind of the public or of the state of the country. Over the previous months, during which the petition had grown, some 600 Chartist Associations had been formed and nearly 100,000 adults were putting aside one penny per week of their wages to keep up agitation for the vote. ‘If you think the signatures to the petition are fictitious—if you think the working classes are not earnest in their claims— you grossly deceive yourselves. Never were the people so determined as at the present moment by every constitutional means to obtain the franchise.’

And turning his attention to poverty which drove the call for reform, he continued: ‘The distress under which they are so severely suffering swells the cry, and renders it more audible and piercing. It is natural—it is proper that it should. When they see their interests disregarded and their feelings insulted, and when they have no hope of better times or better treatment, unless they work out their own redress— when you offer them mere words, and endeavour to stop their cravings by the delusive promises of a Queen’s speech —when you tell them that “you feel extremely for the distresses of the manufacturing districts, which they have borne with exemplary patience and fortitude,” but offer them no remedy beyond your compassion —what can you expect but that they should make their way to this House, and, as you will do nothing for them, endeavour to do something for themselves?’

Duncombe then detailed the impoverished circumstances of the people in Sheffield, Wolverhampton, Burnley, Leicester, Edinburgh and elsewhere, asking: ‘Such being the condition of the people, let me ask you how long you mean that they should remain in it? Let me ask you whether it is possible for them to remain in it? Will you not, at least, give the parties who signed the petition an opportunity of being heard at your Bar, that they may tell you the grievances under which they labour, and the mode in which they think they may be relieved. I should like to hear from her Majesty’s Ministers — from the right hon. Baronet [Sir Robert Peel] at the head of the Government, by what means he proposes to remedy these evils? He surely does not mean to contend that his Income-tax and his tariff will cure them—that Income-tax which is to reduce the middling classes to a level with the lower order, and that tariff which is to throw thousands out of employ, and to drive them into the workhouses. Does the right hon. Baronet mean to resort to the suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act? Does he mean to put down the Chartists by force? I hope not.’

And he concluded: ‘Listen to the earnest appeal they make for a hearing. The least they can ask, and the least you can grant, is that those who are so severely suffering should explain to you the causes and the remedies for their grievances. The hearing cannot occupy long, the number of persons who will appear at your Bar will not exceed six, and it could not occupy more than two days; but if it took ten could it be better spent than in attending to the complaints of those whose patience alone petitions for your consideration? You may think many of their arguments absurd, their schemes of redress wild and visionary, be it so; but do not decide against them without hearing them; do not shut your door against their grievances until you know what they are and the remedies they suggest.’

Speakers for and against hearing the petitioners

The motion was seconded by the Westminster radical MP John Temple Leader, who said it was ‘mere blindness to doubt the sincerity of the working classes, or the increasing numbers with which they came before the House, and prayed to be heard as to their grievances, and to suggest a remedy. He confessed he thought it would be a good thing, not only for hon. Gentlemen opposite, but for all men in that House who were not used to go to public meetings, to hear the petitioners at the Bar, and to be convinced of the intelligence, the ability, and the integrity of the men who were now excluded from the franchise, and who claimed to have a voice in the representation of the people.’

A handful of MPs rose to support the motion, among them the Leicester Whig Sir John Easthope. He made clear that he did not support the Chartist demands, and believed that they would make the destitution of those already suffering still worse. But he added: Feeling as he did for the distress that prevailed amongst the petitioners, and fully admitting his conviction that the principles contained in the charter, and recommended in the petition, would not mitigate that distress, yet he could not refuse their demand to be heard. He could not say to three and a half millions of the people, that he would not listen to their statement of their complaints. He believed that the large majority were sincere, although many were deluded, and some had improperly misrepresented the causes of this destitution, and had pointed out unfit remedies.’

The Tory MP Sir James Graham rejected this argument. ‘Unfortunately the foundation of the petition was generally admitted: the distress was great; the number of petitioners complaining of that distress was large; and their statements were, in many particulars, founded in fact. It was not, therefore, a question of fact to be investigated, it was a question of policy to be adopted; it was not a question of fact to be inquired into, but a question of political remedy to be decided on by the House; and as he could not conceive a course more likely to be disastrous than to excite hopes which were certain to be disappointed, and to hold out expectations which those who consented to the inquiry were aware would be fallacious, he must oppose the present motion.’

The historian and former Whig Minister Thomas Babington Macauley was equally uncompromising. By agreeing to hear the petitioners, MPs would be indicating that they had not yet fully made up their minds. ‘For my own part, my mind is made up in opposition to their prayer.’ There were, he said, parts of the Charter he supported, ‘and in truth of all the six points of the Charter there is only one to which I entertain extreme and unmitigated hostility’. He had voted for secret ballots, and favoured ending the property qualification for MPs. And though he did not favour annual parliaments, he would be content with more frequent elections. ‘But I do not go the length of the Charter, because there is one point which is its essence, which is so important, that if you withhold it, nothing can produce the smallest effect in taking away the agitation which prevails, but which, if you grant, it matters not what else you grant, and that is, universal suffrage, or suffrage without any qualification of property at all. Considering that as by far the most 46important part of the Charter, and having a most decided opinion, that such a change would be utterly fatal to the country, I feel it my duty to say, that I cannot hold out the least hope that I shall ever, under any circumstances, support that change.’

Although he dismissed arguments that universal suffrage must lead to the abolition of the monarchy or the House of Lords, he claimed it would be ‘fatal to all purposes for which government exists, and for which aristocracies and all other things exist, and that it is utterly incompatible with the very existence of civilisation’, for civilisation, he said, ‘rests on the security of property’, and ‘we never can, without absolute danger, entrust the supreme Government of the country to any class which would, to a moral certainty, be induced to commit great and systematic inroads against the security of property’.

The debate continued: John Arthur Roebuck in favour; Lord Francis Egerton against; Benjamin Hawes, though declaring himself ‘a warm advocate for the progressive improvement of the people’ against; Joseph Hume and Thomas Wakely, in favour; Lord John Russell, one of the leading figures in parliamentary battles for the Reform Act, against, declaring that he had come to the House ‘for the purpose of expressing my respect for the petitioners, and at the same time, declaring my abhorrence of the doctrines set forth in the petition’.

Sir Robert Peel’s reply

The prime minister, Sir Robert Peel, then rose to say that he was opposed to the Charter, and opposed to hearing from the petitioners. ‘I think it more just and more respectful to tell them that I do not intend to accede to their petition, than to give them a delusive hearing, which I know can have no useful result.’ And addressing the central demands of the petition, he concluded: ‘I believe that universal suffrage will be incompatible with the maintenance of the mixed monarchy under which we live—I believe that mixed monarchy is important in respect to the end which is to be achieved rather than in respect to the means by which it is gained—that end I understand to be the promotion of the happiness of the people; but in a country circumstanced like this, I will not consent to substitute mere democracy for that mixed form of Government under which we live, and which, imperfect as it may be, has secured for us during 150 years more of practical happiness and of true liberty than has been enjoyed in any other country that ever existed, not excepting the United States of America, not excepting any other country whatever. We may be suffering severe privation. I deeply regret it, I sympathise with the sufferers, I admire their fortitude, I respect their patience, but I will not consent to make these momentous changes in the constitution, with the certainty that I shall afford no relief to the present privation and suffering, with the certainty only that I shall incur the risk of destroying that constitution, which, I believe, if you will permit it to remain untouched, will secure to your descendants as it has secured to you and your ancestors, those blessings which you will never find in any rash or precipitate changes, however plausible in speculation they may appear to be.’

Finally, Thomas Slingsby Duncombe was called to respond to the debate. He was clearly furious. ‘If the industrious classes should ever again condescend to approach this House by way of petition, I will be no party to their degradation, after the manner in which I see them treated,’ he told MPs. There was in the petition, he said, no call for the sweeping confiscation of property, no call for the destruction of the monarchy or the Church. ‘Three millions of men are entitled to a hearing, and so far from the communication of political rights to the working classes endangering your constitution, it would, in my opinion, strengthen its stability.’

MPs then voted: 49 in favour of hearing the petitioners; 287 against.