Palmerston and the publican: a tale of treachery and betrayal known at the top of government

James P. Nagle was trusted among London’s Chartists and Irish Confederates, but the pub landlord betrayed his comrades to a wily police superintendent who trapped him into going further than he ever intended – forcing him to flee the country in fear of his life.

James P. Nagle was well known among the Chartists and Irish Confederates of Seven Dials. He shared their political views, and as a pub landlord he was happy to provide space for them to hold both public and private meetings in which he himself took part.

But after foolishly telling a senior police officer that he would tell all about the Chartists in return for a payment of £2,000, Nagle found himself entrapped into providing damning information for small sums and in fear of being revealed as a police informer. Nagle’s worst fears came true when word of his betrayal got out, and ‘a jury of Chartists and Confederates’ put him on trial him in one of his own pubs. Given ten days to leave the country, he abandoned what must have been a lucrative business and fled to the United States, from where he unsuccessfully lobbied the Home Office and police for the money he felt he was entitled to receive for his services.

Nagle’s story is not well known. Although the information he provided enabled the police to foil what became known as the Orange Tree Conspiracy in the summer of 1848, his name appeared nowhere in the court records when William Cuffay, George Bridge Mullins, William Dowling and others were tried and found guilty of planning an armed uprising. However, his later attempts to extract payment reveal both how the police were able to compromise and turn a previously committed Chartist, and the interest taken in his case at the very highest levels of the Metropolitan Police and Government.

Little is known of Nagle’s background. His surname is common in Cork, and he claimed Sir Edmund Nagle (1757-1830), an Irish officer in the Royal Navy, as his great uncle, so it seems likely that James was Irish – as were many of those living around Seven Dials. Here, in one of London’s poorest and most radical areas, Nagle ran both the Tower public house in Tower Street, and the Three Tuns, a few minutes’ walk away in Moor Street.

Aside from any involvement with Chartism, Nagle’s name appears in the London press only in connection with two court cases. In the first, he was the victim of two men who stole his gold pocket watch, worth £40, while he was drinking with a friend in an Old Compton Street pub (Lloyds Weekly Newspaper, 5 September 1847, p4). And in the second, he complained of being assaulted while trying to throw ‘a man of colour’ named Charles Pebloe out of the Tower public house for being drunk (The Sun, 11 November 1847, p7). Pebloe claimed that he had merely gone inside ‘professionally to amuse the company with some “bone music”’.

Nagle appears to have kept his Chartist activities within the bounds of his own pubs. His name appears only once in the Northern Star, in an announcement that a meeting is to be held ‘at Mr Nagle’s, Three Tuns, Moor-street, Soho, to raise subscriptions for the defence of Robert Crowe, another of the Whig victims’ (NS, 12 August 1848, p5). But his Chartist sympathies and involvement in meetings closed to most casual supporters of the movement were well known to the police.

The full story of Nagle’s betrayal can be found in a small folder in the National Archives consisting of a single letter from Nagle, and an exchange involving Superintendent Nicholas Pearce of F Division, Bow Street, the Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Richard Mayne, and the Home Secretary Viscount Palmerston, about which Nagle himself would have known nothing.

Nagle wrote to the Home Secretary from New York on 12 January 1853. He says that he had previously written to Palmerston’s predecessor Sir George Gray but had received no reply; this, he said, would be his final attempt. A note scribbled on the letter mentions previous correspondence in September 1850s, so this may well be the case – although the earlier letter has not come to light.

In his 1853 letter Nagle introduces himself as landlord of the two ‘publick houses’, and says that ‘it was in my houses that the Chartists and Confederates had held their private meetings. I was their confidential in every respect’.

Nagle claims that when approached by Pearce and another officer, ‘and asked if I would consent to give them the necessary information respecting the Chartists and Confederates I cheerfully consented to do so’. Urged to spare no expense, and promised that he would be ‘liberally dealt with’, Nagle says that he neglected his business and spent money freely to gather information, meeting Superintendent Pearce as often as three or four times a day and during the middle of the night when needed.

He goes on: ‘The first party I was the means of arresting was [the Irish Confederate Francis] Looney and Mr Pearce then handed me £20. Mr P and I then entered into an arrangement that when I would find Dr Mullins… and Mr Dowling, the Artist and Confederate…I would receive £1500. And when I could complete all to his satisfaction and all would be over and quiet I would receive the last instalment of £1500.’

But, he says, despite informing on Mullins and Dowling ‘with some others who were transported’, Superintendent Pearce failed to pay up.

Eventually, says Nagle, his customers ‘began to suspect me for being a traitor. I was accused and assaulted several times and a jury of Chartists and Confederates met at one of my Houses and tried me [and] found me guilty’. Nagle pleaded for time and was given ten days’ grace. ‘In the mean time I received many friendly letters from persons unknown. All told me to leave the country or I should be done for. I took that advice believing it to be a broad hint and I left London.’

Finally, he claims that he had spent £300 ‘trying to gain the necessary information’, and had lost a business ‘worth at least £1,000 a year’, having to leave it in the hands of an ‘ungrateful brother’ when he fled in March 1849.

In a brief handwritten note attached to the letter, Palmerston asks: ‘What foundation is there for his statements? P’.

The note was passed on by Horatio Waddington, permanent undersecretary at the Home Office to the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir Richard Mayne, who replied that though Superintendent Pearce was absent on leave, he personally remembered sufficient of the case to say that no promises were made to Nagle. ‘Nagle did give information, but only when he found his licence was in danger in consequence of the meetings at his House, but I remember my impression at the time was that he gave as little as he thought would answer his purpose and in fact gave information to the Chartists of whatever he could learn from the police.’

When this note was passed to the Home Secretary, he replied: ‘It may be as well to have a report from Pearce also. P.’

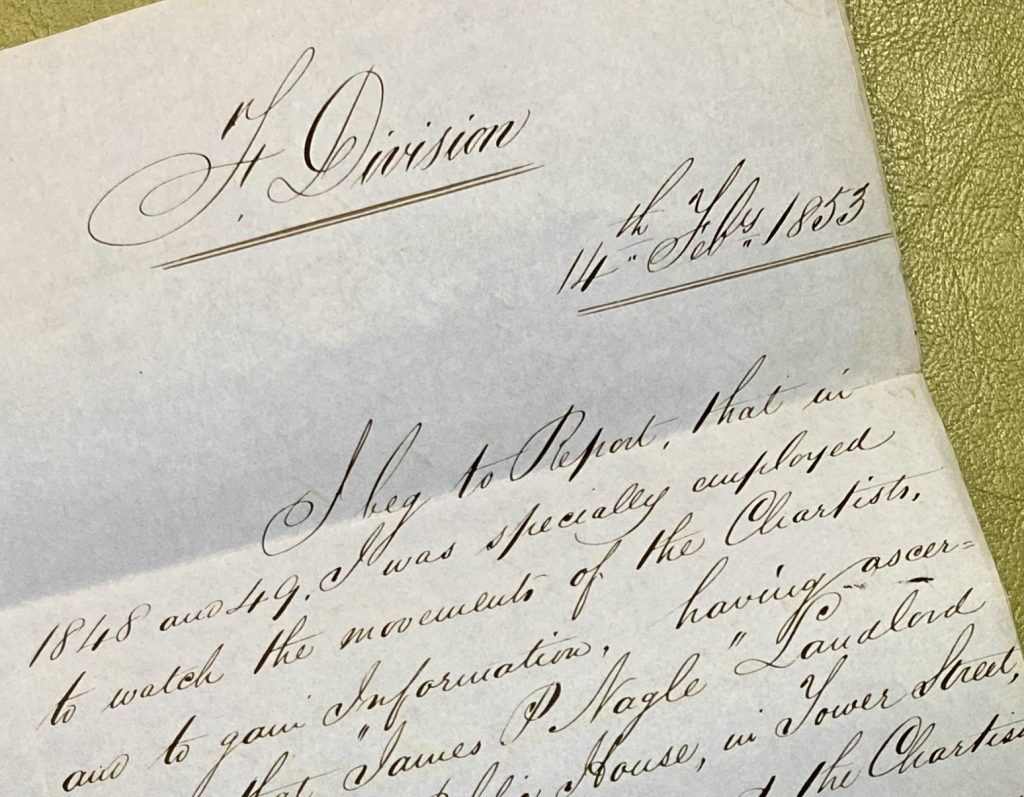

Returning from holiday, on 14 February 1853, Pearce put pen to paper. ‘I beg to report that in 1848 and 49 I was specially employed to watch the movements of the Chartists and to gain information. Having ascertained that “James P. Nagle” Landlord of the Tower Public House, in Tower Street, was a leading man amongst the Chartists and a member of the Irish Confederacy and at whose house meetings of the above named parties was nightly held.’

Pearce says that he already had an informer named Redding, but that he was unable to ‘arrive at the real facts’ as ‘“Nagle” and about 10 others of the leading men, were generally closetted together in an upstairs room, after the general meeting broke up.’ In due course, Redding fell under suspicion, and Nagle and others ‘threatened to murder him’. By now Pearce appears to have thought that Nagle himself might be a better soure of information.

He writes: ‘I saw “Nagle” who told me that he knew all the movements connected with the Chartists, both in London, Ireland, and all the manufacturing towns, and would give me that information for £2,000.’ When Pearce refused to commit to any such sum, Nagle declined to pass on any further information. But he had already gone too far.

As Pearce reports: ‘I then concocted a plan with “Redding” for him to come at a certain hour to a House, where he would find me closetted with Nagle. This he did, which so alarmed the latter, when found in my company (supposed giving information) by a man that he had threatened to murder for a similar act, that “Nagle” then being alarmed and fearing exposure and its consequences, consented to give me information, and I paid him £31 at different times for services rendered.’

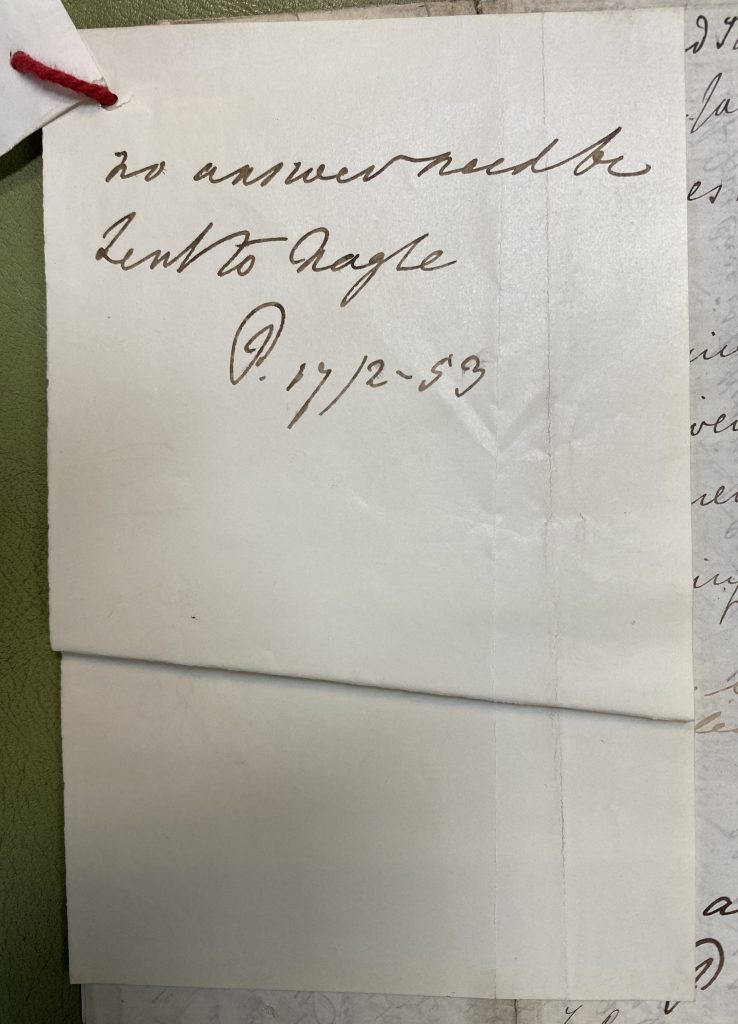

The report evidently satisfied Palmerston, who added a note: ‘No answer need be sent to Nagle. P.’

Superintendent Pearce, a former member of the Bow Street Patrol who had joined the Metropolitan Police as a sergeant when it was established in 1829 and became one of Scotland Yard’s first detectives, was an experience and trusted senior police officer, often brought in to deal with difficult and sensitive cases. On 16 August 1848, armed with his police cutlass and the information supplied by his informers, Pearce led the raid on the Orange Tree public house that saw William Cuffay, the leader of the London Chartists, and others arrested and transported to Australia.

Perhaps surprisingly, however, in all the criminal cases brought against the Chartists as a result of that summer’s agitation there is only a single passing mention of a meeting ‘at Nagle’s’ and no mention at all of James P. Nagle or his part in betraying the proposed rising.

Nagle himself disappears from the record after 1853, and most likely remained in the United States; attached to his letter is a printed slip, labelled as ‘my address’, which names him as secretary of the United States Mutual Benefit Association of New York. Of those against whom he claimed to have informed, Francis Looney was arrested in June 1848 for a seditious speech and sentenced to two years in prison; William Dowling, best remembered today for the sole surviving portrait of his fellow prisoner Cuffay, was arrested and sentenced in September to be transported for life to Australia; and two months later a similar sentence was passed on George Bridge Mullins, who was to have led one of four centres of the rising at Seven Dials.

Much remains unanswered about Nagle’s involvement in all of this. Was he, as he seems to suggest, merely a concerned citizen who anxious to help the police; did he betray his comrades in the hope of a huge cash reward; or was his offer to do so an attempt to taunt Superintendent Pearce that went very badly wrong for Pearce and those who had trusted him?

Notes and sources

James P. Nagle’s letter and the internal police and Home Office correspondence can be found at the National Archives in HO 45/5002.

The best account of the Orange Tree Conspiracy and the events of summer 1848 in the capital remains David Goodway’s London Chartism 1838-1848 (Cambridge University Press, 1982).

Reports of the Chartist trials of 1848 can be found on the excellent Proceedings of the Old Bailey website.

William Cuffay ended his days in Tasmania. This post on the Chartist Ancestors blog traces his steps in what was then Van Diemen’s Lane and includes William Dowling’s portrait of the London Chartist leader.

Family historians have created online accounts of the lives of George Bridge Mullins and William Dowling.