Cartoons depicting magistrates and cavalrymen on 10 April 1848

This page looks at a set of cartoons depicting the military arrangements put in place in preparation for the Chartist monster meeting of 10 April 1848.

This is one of a number of articles dealing with the Third Petition for the Charter. See also:

London Convention and National Assembly – 1848

Full text of the Petition – 1848

10 April ‘monster meeting’ on Kennington Common – 1848

Document: Cartoons of magistrates and military – 1848

Object: Police truncheon for a special constable – 1848

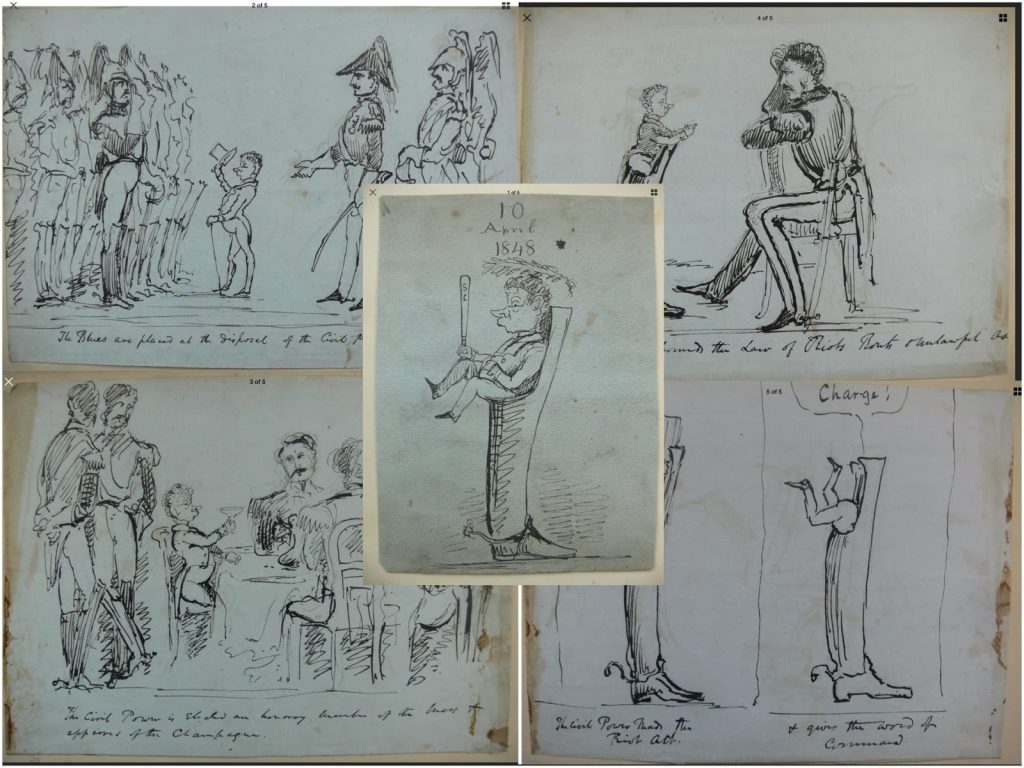

Hand drawn and contemporary with the Chartist Meeting on 10 April 1848 on Kennington Common, this set of five cartoons shows Thomas James Arnold, who as police magistrate on duty on the day of the meeting, provided civilian oversight and control of at least part of the military presence – in this case the Royal Regiment of Horse Guards.

All five of the cartoons are depicted further and discussed below. A sixth cartoon dated 1842 which clearly identifies both the cartoonist and the principal character is also shown.

Where do the cartoons come from?

None of the five cartoons is signed and Arnold is not named. But it is possible to be confident in the artist and the subject. All five come from a Victorian album, which has been broken up for sale. An earlier cartoon (Image 2), dating to 1842, came from the same album, is clearly in the same hand, and provides a great deal of useful information.

This earlier cartoon appears within a letter sent by John Paget to a barrister by the name of Holland at Harcourt Buildings in London – one of the Inns of Court. John Paget (1811-1898) was himself a barrister, police magistrate and writer. As a young man, he had supported the Reform Act of 1832 and became a founder member of the Reform Club in 1836. Professionally, he entered the Middle Temple in 1835 and was called to the bar three years later. Subsequently he became a police magistrate at Thames police court from 1864 and later at the Hammersmith and Wandworth courts.

Paget was apparently a contributor to Blackwoods Magazine from 1860 to 1888, and in 1874 authored Paradoxes and Puzzles, which included accounts of sensational crimes.

By a great piece of luck, this earlier cartoon depicts Thomas James Arnold, and names him in the text. Arnold (1804-1877) had been called to the bar in 1829 and appointed a magistrate at Worship Street police court in 1847. He later transferred to the Westminster court in 1851. Arnold too was an author, writing legal manuals and translations of classical literature.

It is possible that the cartoons appeared in print. The third in the series has, ‘arnold police mag’ written in pencil on the mount; however, no publication in which they featured has been identified.

Sequence of the cartoons

The five cartoons concerning the events of 10 April 1848 form not just a set but a story. While the first is more of a title page, the others represent a sequence through from the time Arnold is introduced to the ‘Blues’ to the celebrations at the successful conclusion of the day.

Neither is there any difficulty in identifying the order of the cartoons as they are all still glued to the pages of the album in which they have sat for the past century and a half.

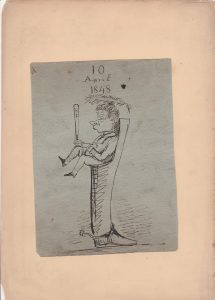

Cartoon 1. Thomas James Arnold on 10 April 1848

“10 April 1848” by John Paget.

The first cartoon in the series serves as a sort of title page to the set. It shows Thomas James Arnold, police magistrate at Worship Street police court – and the subject of the series of illustrations.

Arnold, a small, slightly plump man – almost a Tweedledum/dee figure, though John Tenniel’s illustration of the rotund twins did not appear until 1871 – is seated in a giant, spurred boot. The boot – and the idea of a small man occupying it – would have been familiar to audiences of the day from the famous 1827 William Heath cartoon picturing the Duke of Wellington.

Arnold is holding a truncheon marked SC – presumably for special constable. He appears to be wearing his barrister’s wig and over his head there is a laurel wreath. Obviously this was drawn soon after the event, when the forces of law and order felt themselves to be the victors. The only other text is a date: 10 April 1848. It is this date which demonstrates without doubt that the cartoons are intended to show Arnold’s role on the day of the Chartist rally at Kennington Common which had been declared illegal and which the authorities intended to suppress.

Arnold’s role that day was as one of nine magistrates in charge of elements of the military – in Arnold’s case, the Royal Regiment of Horse Guards (the Blues).

The cartoon is approximately 14cm by 19cm. While the finished version is in pen and ink, there are lighter pencil marks below where Paget sketched out a rough version first. The sketch is still glued to the page of an old album, where it has probably been preserved since not long after it was drawn. It is the only one of the five cartoons not to back any other illustration.

Cartoon 2. The Civil Power takes command of the Blues

“The Blues are placed at the disposal of the Civil Power” by John Paget.

The second cartoon in the series shows Thomas Arnold, cane in one hand, raising his hat as a senior officer introduces him to the men of the Blues. Arnold was not an imposing figure. Paget invariably draws him as a small but simultaneously somewhat puffed-up looking man, both in the series of 1848 cartoons and in the earlier 1842 cartoon in which he is shown bare-knuckle boxing a rather larger barrister!

The cartoon is approximately 25cm by 17cm.The finished version is in pen and ink, but there are lighter pencil marks below where Paget sketched out a rough version first. The reverse of the sheet on which it is drawn appears to have been taken from an accounts book, recording payments for shale coal. The sketch is still glued to the album page, the reverse of which holds cartoon 3, and that page in turn is attached along one edge to the page holding cartoons 4 and 5.

Cartoon 3. Explaining the law of riots and unlawful assembly

“The Civil Power expounds the Law of Riots, Rout and Unlawful As[sembly]” by John Paget.

The third cartoon in the series shows Thomas Arnold, perched in the giant boot representing the Duke of Wellington, setting out the law for a senior officer of the Blues. While Arnold is in his somewhat pompous element, the explanation is clearly giving the officer a headache.

Arnold was one of nine police magistrates given control over elements of the army on 10 April 1848 – the military being able to act only under the direction of the civil authorities and in aid of the civil power. It would have been important for officers to be aware of the limitations on their actions.

The cartoon is approximately 23cm by 17cm. The finished version is in pen and ink, and there are lighter pencil marks below. The sketch is still glued to the album page, the reverse of which holds cartoon 2, and that page in turn is attached along one edge to the page holding cartoons 4 and 5.

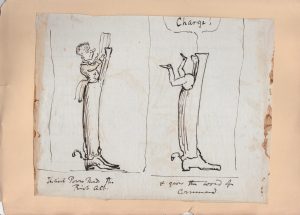

Cartoon 4. Riot Act and the command to charge

“The Civil Power reads the Riot Act. & gives the word of Command” by John Paget.

The fourth cartoon in the series shows Thomas Arnold emerging from the giant boot – representing the Duke of Wellington, who was in overall control of the defence of London on the day of the Chartist meeting on Kennington Common.

On the left of the sketch, Arnold, who had oversight of a military detachment (in this case the Royal Regiment of Horse Guards), reads the Riot Act ordering protestors to disperse. And on the right, he gives the word to charge – while simultaneously disappearing down inside the boot.

In the event, Arnold would never have issued the command. Most of the crowd dispersed peacefully, and those who attempted to cross the Thames were confronted by police officers rather than the cavalry.

The cartoon is approximately 24cm by 18cm. The finished version is in pen and ink, there are lighter pencil marks below. The sketch is still glued to the album page, the reverse of the same page holds cartoon 5, and that page in turn is attached along one edge to the page holding cartoons 2 and 3.

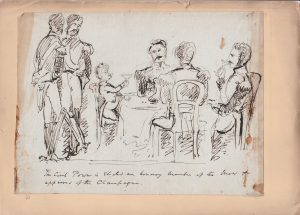

Cartoon 5. Champagne with the Blues

“The Civil Power is elected an honorary member of the Blues & approves of the Champagne” by John Paget.

The final cartoon in the series shows Thomas Arnold seated at a table with three officers of the Royal Regiment of Horse Guards while two others look on. Both Arnold and the officer opposite him hold Champagne glasses.

The scene clearly takes place after the events of 10 April 1848 have passed successfully as the men celebrate. According to the caption, Arnold, a police magistrate who embodied the Civil Power on the day, and therefore had control over a section of the military, is being made an honorary member of the Blues. Arnold was one of nine magistrates acting in this way on the day.

The cartoon is approximately 25cm by 18cm. There are lighter pencil marks below where Paget sketched out a rough version, and the sketch is still glued to the album page, the reverse of which holds cartoon 4, and that page in turn is attached along one edge to the page holding cartoons 2 and 3.

Outstanding questions

Did John Paget draw this sequence of cartoons for his own amusement and that of his friends? Or was it published at the time? If it did appear in a ‘police mag’, then so far it has not been identified: the British Newspaper Archive has a number of promising titles, none of which, unfortunately seem to have been in publication in 1848.

Can the senior military officer be identified? It appears that the officer pictured in the second, third and fifth cartoons may well be the same man and would presumably be identifiable from military records and the uniform he is wearing. Newspapers at the time reported that, ‘Four squadrons of the Royal Horse Guards (Blue) marched from the cavalry barracks, at Spital, yesterday morning, for Knightsbridge, under the command of Colonel Bouverie’ (London Morning Herald, 10 April 1848). So could Colonel Bouverie be the officer depicted? He is shown here in 1860 after being promoted to General.

It appears that only a part of this force was deployed at Kennington. One report written on the day and widely reproduced soon after the event (for example, in the North Devon Gazette of 13 April 1848), recounted how: ‘At half-past six o’clock this morning, two companies of the royal Horse Guards, with four pieces of ordnance, arrived, and were accommodated with a temporary residence at some extensive livery stables in the neighbourhood.’ So maybe a less senior officer took charge of these companies and liaised directly with the magistrate.

Finally, what part did Arnold play after 10 April? There were serious clashes between the police and Chartists in and around Bethnal Green throughout May and into the following month.

On 12 June, Peter Murray McDouall, the only member of the Chartist executive still in the capital, arrived at Bishop Bonner’s Fields, where a further huge meeting was planned – to the consternation of the authorities, who duly mobilised ‘an immense mass of police armed with cutlasses’. Arnold and McDouall met shortly after 1pm. ‘McDouall enquired whether indeed the government proposed to suppress the demonstration. The reply was that the proposed meeting was illegal and would be prevented.’ Faced with overwhelming odds, McDouall and the organising committee had no option but to call off the meeting and send the crowd home. By 5pm, the authorities had been able to stand down the special courts that had been assembled to deal with mass arrests; Arnold himself remained on duty until 9.30pm, but the threat was over (see David Goodway’s London Chartism 1838-1848 (Cambridge University Press, 1982).

Arnold may have been something of a figure of fun to his friends, but his willingness to use overwhelming force to suppress Chartist gatherings in 1848 was clearly no joke.

The cartoons depicted on this page are in the collection of Mark Crail, who runs the Chartist Ancestors website.