The O’Connor tartan and Scotland’s radical weavers

With a range of O’Connor tartan plaid clothing to choose from that included scarves, cravats, dresses, handkerchiefs and waistcoats, the well-dressed Chartist of the late 1840s would have been quite a distinctive sight.

There was nothing remotely authentic about an O’Connor tartan. Feargus O’Connor was Irish – a descendent of the High Kings of Ireland, no less, or so he often said – and in this period there were no Irish tartans. So it had fallen to the radical weavers of the Scottish lowlands to come up with something of their own devising with which to honour the Chartist leader, and to take advantage of the business opportunity offered by the thousands of Northern Star readers, enlisting their help to revive a depressed weaving industry.

It is not entirely clear where the O’Connor tartan originated. The earliest mention appears to be a brief entry in the Northern Star‘s ‘local and general news columns’ in 1842 which reflects the economic desperation of the weavers: ‘BANNOCKBURN – Trade is in a wretched bad state; the people have nothing to do, and very many are in actual starvation. A new tartan has just been created here, and it is called after our champion – “the O’Connor tartan.” It will be much worn in Scotland by the working classes, and will turn out a good speculation to the manufacturer’ (NS, p.3, 15 January 1842).

But after this, there was no further mention of Chartist tartans for a further five years. It may well be that no manufacturer could be found who was willing to put up the capital. Then, in the autumn of 1847, as O’Connor and Ernest Jones were preparing for a speaking tour of Scotland, the Northern Star carried a flurry of mentions of the O’Connor tartan. Announcing that the two Chartist leaders would visit Kilbarcan (more properly Kilbarchan) and then spend two nights in Glasgow, the paper’s ‘To readers and correspondents’ column added: ‘Mr O’Connor will have much pleasure in accepting the proposed present of a tartan plaid’ (NS, p.5, 30 January 1847). Kilbarchan was a weaving community some distance to the west of Glasgow; it had a long radical history and was something of a Chartist stronghold; it was presumably on this stop of his tour that O’Connor anticipated accepting the gift.

The same column, however, placed the manufacture of Chartist tartan plaid some 75 miles to the east of Edinburgh, at Kirkcaldy, Though once again, the paper got the spelling wrong as it reported: ‘We have been favoured with a sight of a specimen of the O’Connor tartan, manufactured in Kirkaldy, in honour of the member for Nottingham, and must pronounce it in design and execution both as regards the quality and the colours – “excellent.” As the O’Connor clan of Land and Charter men far exceeds in numbers the entire of the original “clans,” in their palmiest days, we have no doubt that this plaid will become a favourite with tens of thousands, both male and female. Men’s plaids and waistcoats, and women’s dresses, shawls, &c., will look equally beautiful, picturesque and becoming.’

Kirkcaldy certainly had a weaving industry and a Chartist presence, but it mostly manufactured coarse linens used as sail cloths, and its branch of the National Charter Association was never as big or as active as that in Kilbarchan, which had a Chartist public hall and Chartist church. At one point, Kilbarchan had as many as 800 handlooms, and its weavers had been enthusiastic supporters of a Scottish insurrection in 1820 that had sought to form a provisional government. The ‘radical war’ ended with a wave of executions and with other leaders transported to Australia.

It is possible that the tartan (the design) had originated in Bannockburn near Stirling and was then adopted by weavers in both Kilbarchan and Kirkcaldy for their plaids (the material). It may also be that the Northern Star mixed up its Scottish towns – which would have been somewhat embarrassing for its editor, George Julian Harney, who in 1841 had married Mary Cameron, the daughter of a radical Scottish weaver from Mauchline in Ayrshire. Or it may be that there were rival designs:. Unfortunately, there is not a single description of an O’Connor tartan which might help unravel the mystery. And while an O’Connor tartan is listed in the Scottish Register of Tartans, the version there appears to date to no earlier than 1994.

Whatever the sequence of events, the Kilbarchan weavers were first to market. For in that same issue of the Northern Star, there was an advert to announce that William Love had been appointed as the agent for the O’Connor tartan in Glasgow, and would soon have a large supply of ‘vestings, cravats, plaids, shawls, &c.’ (NS, p.10, 30 November 1847). It went on: ‘It has been designed by the weavers of Kilbarchan in honour of Mr O’Connor, and they have formed a Joint Stock Company for its manufacture, for the double purpose of supplying the friends and admirers of Mr O’Connor, and of employing a portion of the villagers during the winter.’

Other agents followed. James Nothenvell, bookseller and newsagent, announced that he had been appointed to sell the tartan plaid in Paisley, where he kept an assortment on hand (NS, p.4, 30 November 1847). In London, members of the Greenwich, Deptford and Woolwich branch of the Land Company and Charter Association formed themselves into an ‘O’Connor Tartan Club’ through which members could save small weekly sums towards the various vests (waistcoats), scarfs and other items sold by Mr Sweetlove, the local Northern Star agent (NS, p1. 18 December 1847). And at Hammersmith, Land Company members formed a ‘hat and clothes club’ for much the same purpose – hoping to buy their plaids from Edmund Stallwood (NS, p.1, 29 January 1848).

On a larger and more commercial scale, or at least of greater ambition, was this advert: ‘Mr John Gregory, Draper, Eccles, near Manchester, begs to inform his Democratic friends in Manchester, Stockport, Ashton, Hyde, Oldham, Bury, Heywood, Bolton and Leigh, that he has become an Agent for the sale of THE O’CONNOR TARTAN, and intends to wait upon his friends, in the above-named places, in the course of a few days, with a select stock of Ladies’ Shawls, Scarfs, Handkerchiefs, Silk and Woollen Dresses, Gentlemen’s Vestings, &c. &c., when he trusts he shall receive the patronage and support of his numerous friends’ (NS, 12 February 1848).

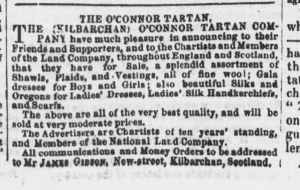

It was also possible to buy direct from the weavers. An announcement in the Northern Star read: ‘The Kilbarchan Co-operative Company for Manufacturing the O’Connor Tartan have much pleasure in announcing to the Chartists and admirers of Mr O’Connor that they have for sale a splendid assortment of plaids, shawls, vestings, silk and gala for dresses, also silk handkerchiefs and scarfs. Parties wishing the above beautiful Tartan can be supplied by sending a Post-office order, payable at Paisley, to James Gibson, Kilbarchan’ (NS, p.4, 20 November 1847).

They advertised again the following year, once the excitement and disappointment of the third Chartist petition had passed its peak, stressing: ‘The Advertisers are Chartists of ten years’ standing, and Members of the National Land Company’ (NS, p.4, 16 September 1848). But their advertising appeared to make little impact. A month later the Northern Star carried a question from Thomas Mennell of Wakefield: he had several orders for O’Connor tartans and wanted to know where they could be bought (NS, p.4, 21 October 1848). He received no reply.

But the story of the Chartist tartan was not quite over. In March 1849, an advert headed ‘Victim Fund’ appeared in several successive issues of the Northern Star announcing what was in effect a prize draw for ‘two beautiful plaids of O’Connor and Duncombe tartans’. Curiously, there had been no previous mention of a tartan for Thomas Slingsby Duncombe – and nor would it be mentioned again. Tickets (‘subscriptions’) were priced at 6d and the ‘subscription sale’ was to take place at Ross’s University Temperance Hotel, 59, South Bridge, Edinburgh, with proceeds to be given to the Victims Funds of England and Scotland.

Though not named in the initial adverts, the draw appears to have been organised by the Chartists of Gorgie Mills (again, often mistakenly given by the Northern Star as Georgie Mills), an active radical group who paid substantial sums to the National Land Company. In a letter to the Star, William Meehan, writing on behalf of ‘the Democrats of Gorgie Mills’ was able to report that there had been 309 subscribers to the draw – indicating a total of £7 14s 6d raised for the cause. A meeting had been held to select the winners, and James B Hainsworth of Sheffield and James Dickson of Lynn were declared the ‘successful subscribers’, after which ‘the meeting broke up, highly delighted with the proceedings of the evening’.

And that, curiously, was the final ever mention of an O’Connor tartan.

Further information

Matthew Roberts discusses the role tartans played in the ritual of gift-giving in his book Chartism, Commemoration and the Cult of the Radical Hero (Routledge, 2020).

The National Trust for Scotland maintains an 18th century weaver’s cottage in Kilbarchan in which tartans are produced. Find out more.