Chartist beverages and breakfast powders

Chartist breakfast powders were cheaper than tea or coffee, and said to be healthier. In addition, a dutiful Chartist might also aid the cause and deprive the government of duties on imported goods by buying their supplies of the untaxed beverage from one of the radical bookshops or manufacturers who advertised in the Northern Star. They often promised a donation to the cause for every pound of powders sold.

In the mid 1840s, there was quite an industry in Chartist breakfast powders, which were intended to be steeped in hot water before drinking, and several manufacturers sprang up to meet demand. They sold their products directly, by post or through a network of local agents who might double as Chartist lecturers, organisers and journalists, deriving an income from breakfast powders and a host of other Chartist products such as boot blacking, ink, and O’Connor tartan handkerchiefs, scarfs and clothing for both men and women.

But this lucrative market did not last. What eventually killed it was not so much business failure or a decline in Chartist commitment but a fundamental cross-party shift in economic ideology from protectionism to free trade.

‘Orator’ Henry Hunt and the Excise

The radical orator Henry Hunt had first made breakfast powders popular, if not notorious, some twenty years earlier, when in search of a ready income he began to roast and grind the rye grown on his farm at Broadwell in Sussex. In the wake of his arrest at Peterloo in 1819, Hunt clearly saw an opportunity to combine one of his many business interests with his politics, vowing ‘not to taste one drop of taxed BEER, SPIRITS or TEA, till we have brought these magistrates to justice’.

Others may have got there first. ‘At a window in Horsepool-street in Leicester, there is a paper with “Radical Breakfast Powder sold here” printed thereon,’ confided the London Star gnomically in its issue of 29 November 1819. The idea clearly caught on, with the British Press reporting: ‘On Saturday, in Wolverhampton, a quantity of imitation coffee was seized upon the premises of T. Worth, agent for the Argus, Black Dwarf, and other seditious publications in that town. He calls it Radical Breakfast Powder; it is composed of red wheat and Scotch barley, and he has been selling it at 1s per lb, what could not cost more than 3d’ (13 December 1819). Whether either or both of these products were Hunt’s is not clear – but it would not have been a hard idea to copy.

Hunt soon ran into difficulties. Hostile newspapers were not slow to point out that the cost of the corn, especially when adulterated with horsebean and other cheap vegetable matter, would not come to more than 4d a pound – accusing him and other manufacturers of profiteering. Then, in 1822, Excise officers seized Hunt’s corn stock and ‘the apparatus for manufacturing his radical breakfast powder’ from ‘his manufactory near Christ Church, on the Surrey side of Blackfriars bridge’ (Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, Saturday 26 February 1820).

Hunt was fined £200 and others were similarly prosecuted, newspapers making much of the discovery of the ‘powder’ at the home of the Cato Street conspirator Arthur Thistlewood. But even the government of the day appears to have thought the Excise had over-reached itself, and in 1822 the law was changed to permit the sale of untaxed breakfast powders.

Hunt continued in business throughout the legal crackdown, as it would appear did his competitors, whom he denounced as frauds and imposters. And though there appear to be no surviving examples of Hunt’s Breakfast Powder, an advert from Wooler’s British Gazette provides a description of the packaging: ‘To protect the public in future against such frauds, HUNT’S GENUINE BREAKFAST POWDER will be sold wrapped in Blue Paper only, upon which will be pasted a printed Label of Directions, signed with his own Hand as under, to imitate which is felony’ (19 November 1819).

There were sporadic mentions of breakfast powders in the press throughout the 1820s and 1830s, notably Haycraft’s Bengal Breakfast Powder, ‘made from the Cocoa Nut’, but their association with radicalism soon disappeared. The link was revived with the emergence of Chartism, and especially the high-circulation Northern Star which gave easy access to a large national market.

1842: a burgeoning Chartist market

The Leicester partnership of Crow & Tyrrell appear to have been the first to recognise the potential of a Chartist link, advertising their ‘Chartist Beverage or improved British Breakfast Powder’ at a price of 8d per lb in the Northern Star of 5 March 1842 (p.2). Smaller packets were also available. They promised to give ‘three shillings out of their receipts for every 100lbs weight sold to Agents, to the Executive Council of the National Charter Association’. This amounted to an offer of a three shilling donation for every £3 6s 8d of powders sold. Two weeks later, the firm was able to report that the proceeds from sales of the Chartist beverage already amounted to 8s 3d (NS, 19 March 1842), which would suggest sales of just under 300lb (roughly 136kg).

From their premises at 81 Belgrave Gate, Leicester, Crow & Tyrrell would become the most persistent advertiser, and probably the largest vendor of Chartist breakfast cereals, for the next three years. But they were not alone. Jackson’s, a second Leicester firm, advertised its own ‘greatly improved breakfast powder’ in the same issue of the Northern Star that saw Crow & Tyrrell make their debut. Helpfully, the advert, on page 4, advises that the breakfast powder is ‘to be prepared precisely the same way as Coffee’. It claimed no particular radical or Chartist affiliation, however.

Others swiftly saw the opportunity. Wiliam Atkinson of 98 Travis Street, Manchester announced that he would give 10 per cent of his proceeds to the Executive Council on all sales above 2s 6d (NS, 23 April 1842, p8). Crow & Tyrrell countered with a claim that they had received a letter signed by twenty-five Nottingham Chartists who had tried their product ‘and speak of it in very high terms’ (NS, 30 April 1842). No doubt with an eye on its own revenues, the Star’s editor ran the claim in his ‘To readers and correspondents’ column. The following month, Edwards Brothers, Manufacturers, of 99 Blackfriars Road, London, was advertising for agents to sell its own breakfast powders, claiming that, ‘The Chartist Societies are adopting its exclusive use; many prefer it to Coffee, and its Cheapness enables all to effect a very important saving. It is more nutritious than either Tea or Coffee’ (NS, 21 May 1842).

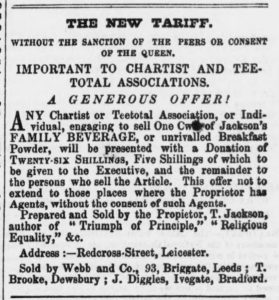

With what must have been a potentially lucrative battle for customers now heating up, Jackson promised he would give every Chartist or Teetotal Association or individual selling a hundredweight (112lbs) of his ‘family beverage’ 26s, of which 5s would go to the Executive and the remainder to the vendor (NS, 28 May 1842). Promoting his own radical credentials, the advertiser now identified himself as T. Jackson of Recross Street, Leicester, the author of such works as Triumph of Principle and Religious Equality. And in something of a business coup, Crow & Tyrrell signed up Joshua Hobson, the printer and publisher of the Northern Star as their general wholesale agent for Yorkshire (NS, 11 June 1842). Between them, Hobson and James Leach of Manchester, who became wholesale agent for Lancashire, appear to have sold the bulk of Crow & Tyrrell’s powders. Other vendors, however, included well-known Chartists such as George Julian Harney, then in Sheffield, Abel Heywood in Manchester, the Loughborough Chartist John Skevington, Leicester’s Thomas Cooper, and the Star’s London correspondent Edmund Stallwood.

That summer, the Northern Star was able to report that proceeds to the executive from the sale of Crow and Tyrrell’s breakfast powders in the space of less than a fortnight between 18 and 30 July came to £4 5s 9d (NS, 6 August 1842). This would equate to sales of a little over 25cwt, a massive 1,270kg, of breakfast powders. The week ending 6 August brought proceeds of £4 9s 3d (NS, 13 August 1842), while sales between 16 August and 3 September generated a further £2 10s 3d.

The business was not without its critics. An anonymous Newcastle correspondent in the British Statesman, edited by the Chartist James Bronterre O’Brien, did not hold back: ‘At this time it is of the utmost importance to caution the people against the course pursued by certain mercenary wretches, who are turning the people’s distress to account, in a manner the most fiendish and unfeeling. These wretches contrive, with ruthless hands, to extort gain from that very misery which they pretend to deplore; assuming all the various characters of Chartist pill-venders, Chartist blacking-manufacturers, breakfast-powder agents, and basket-makers and venders, some of which are the most confirmed hypocritical villains that ever cursed society. Let the working classes spurn as vipers such imposters and mercenary wretches – who would betray Jesus Christ for a shilling’ (27 August 1842).

Most, however, did not share this antipathy. In addition to the money donated by manufacturers to the cause, Chartist breakfast powders supported the work of the leadership more directly at local and national levels. By selling such Chartist products activists who lacked the wealth of their counterparts in the anti-corn law movement, could sustain themselves and their families, especially as the social composition of Chartism as a whole was typically poor and lacking in the resources needed to support them. As the historian Paul Pickering comments: ‘This left many of the full-time leaders of Chartism to make a living as best they could in the “trade of agitation”.’

The practicalities of breakfast powders

Samuel Bamford, the Middleton radical and veteran of Peterloo, was said to have found ‘corn coffees’ to be ‘unpalatable’. Probably referring to Hunt’s product, Richard Carlile took a more positive view, writing: ‘Nothing can be more wholesome than the Breakfast Powder or British Herb Tea, as the former I understand to be manufactured from the best wheat’ (The Republican, 1820, cited on The Old Foodie blog). Carlile, who was nothing if not eccentric, added: ‘For a considerable time last winter I made a liquor as a substitute for tea from hay, and I found it very pleasant. I would prefer it to the Breakfast Powder, or the British Herb Tea, which are now selling in London in such large quantities.’

The Huddersfield draper and Chartist activist Lawrence Pitkethly had good reason to appreciate the Chartist beverage. In January 1843, he set off for a tour of Canada, enduring a long and fairly unpleasant transatlantic crossing. His diary for Sunday 19 January, eventually reproduced in the Northern Star on 15 April, records, after the best part of a week at sea and still within sight of the coast of Ireland: ‘Got up at seven – there was now much sickness and a considerable noise; the breakfast was therefore not very comfortable. We had some Chartist breakfast powder, which we enjoyed more than coffee or tea.’

A Chartist breakfast may often have been a fairly basic affair, consisting of no more than hot water added to breakfast powder. But we can only speculate about how this might have tasted. As different manufacturers used different grains, maybe each ‘brand’ had a distinct flavour; the roasting method used to dry the grains before grinding also imparting something unique to the taste. Though some manufacturers used wheat, according to their advertisements, Henry Hunt had claimed to use rye, which may well have marked it out from competitors. One modern bakery that uses rye flour describes a ‘mild flavour that’s nutty, earthy and slightly malty’, and says that it has a ‘greener’, fresher flavour than other grains. It cautions, however, against assuming that the typical taste of modern rye bread reflects the true flavour of rye as caraway is often added to the mix.

There must also be questions about the texture of breakfast powders. They were sold as a beverage, and at least one manufacture says the process of using them was identical to that of coffee. Does this mean that the grinding process created a coarse powder, not all of which would dissolve in hot water, leaving something similar to coffee grounds at the bottom of the pot? The same bakery mentioned above also says that, due to its relatively low gluten content, rye flour has a ‘distinctively chewy quality’ when made into bread. The Chartist beverage may have produced a rather thicker liquid than tea or coffee, perhaps with the consistency of a milkshake.

Free trade and the downfall of the Chartist breakfast

Chartist breakfast powders apparently proved lucrative both for their manufacturers and for the National Charter Association, which for a time was able to rely on getting around £3 a week in donations from their sale. But by the end of 1843, the business model appeared to be coming under strain. The partnership of Crow & Tyrrell was dissolved that October (NS, 4 November 1843), and for the next eighteen months, all was silence. Then, in March 1845, William Crow popped up in the pages of the Northern Star once again, to announce that he had moved to 77 Bedford Street in Leicester and was now the manufacturer of Crow’s Franklin Beverage Powder (NS, 8 March 1845).

After advertising one more time, however, Mr Crow fell silent once again. Neither he nor any other manufacturer of breakfast powders would advertise in the Northern Star beyond that spring.

In the end, the market for Chartist beverages and breakfast powders was destroyed not by any failing on the part of the manufacturers or lack of commitment on the part of the Chartists, but by larger economic forces as the government of the day abandoned protectionism, and its reliance on import duties, for free trade and income tax.

In 1842, Robert Peel’s government cut the duty coffee imported from British colonies from 8d to 4d per pound, and on ‘foreign’ coffees from 15d to 8d. It made further reductions in 1844, and would eventually abolish them altogether. At a stroke, Peel had undermined two of the three planks on which the successful sale of Chartist breakfast powders rested: they were no longer markedly cheaper than the coffee they were intended to replace; and by buying coffee Chartists were no longer providing the government with taxes. All that remained was the possibility that by buying breakfast powders Chartists could hope to see some small commission paid to the National Charter Association. It was not enough to sustain the businesses which had once thrived on working-class customers’ need for a cheap, nutritious and flavoursome breakfast.

From now on, coffee – and increasingly tea – would be the beverage of choice.

Sources and further reading

‘Chartism and the “Trade of Agitation’ in early Victorian Britain”, by Paul Pickering in History 76:247, June 1991. Available on JSTOR (log-in required).

The Peterloo Massacre: the Journal of Henry Hunt (part 2) on the Archives+ partnership of archive & local history organisations at Manchester Central Library.

Radical Breakfast Powder on The Old Foodie blog, 30 January 2014. Accessed 31 October 2023.

All newspapers cited in the article were accessed via the British Newspaper Archive.