The simple and secular funeral of William Lovett

By the time William Lovett published his autobiography in 1876, he was able to look back on a long life that, in material terms, had proved to be tough and unrewarding, but which also encompassed half a century of unstinting effort on behalf of the working class to whom Lovett had devoted his life, and a record of political commitment to the radical causes that defined the era.

Precisely though not concisely titled The Life and Struggles of William Lovett in his Pursuit of Bread, Knowledge, and Freedom, With Some Short Account of the Different Associations He Belonged to and of the Opinions He Entertained, the book had been a long time in preparation. Excusing himself for any repetition in its two volumes, Lovett remarked in the preface that “it was begun in 1840, and has been added to from time to time up to the year 1874”.

This is one of a number of articles about William Lovett. See also:

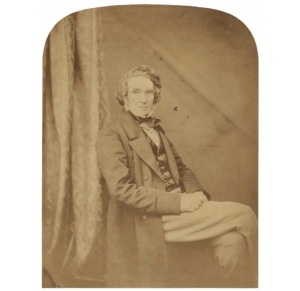

William Lovett, 1800-1877

Knowledge Chartism: William Lovett, the New Move and the National Association

Funeral notice for William Lovett

On 8 August 1877, within a year of the book’s appearance, Lovett died. His various ventures as a ropemaker, cabinet-maker, shopkeeper, teacher and bookseller had not made him a wealthy man, and by all accounts he died in poverty, leaving Mary (Solly), his wife of 50 years, reliant on the charity of friends and such support as their surviving daughter, also Mary, could provide.

Lovett’s death at his home, 137 Euston Road, London, did not go unnoticed. Two days later the Conservative-leaning Pall Mall Gazette recorded the passing of “another well-known Chartist leader”; it recalled both his “active part” in the movement for the abolition of stamp duty, and his role in “drawing up most of the petitions and addresses” in connection with Chartism.

Variations on this short obituary subsequently appeared in countless local newspapers across the country. It cannot have escaped the attention of many former Chartists, who must have known of Lovett’s role as author of the People’s Charter, secretary to the first Chartist convention, political prisoner, and rival to Feargus O’Connor for the leadership of Chartism.

O’Connor’s own death, in 1855, had been the occasion for a great public display of mourning. His funeral cortege, consisting of a black-plumed hearse and four horses attended by a dozen men with wands, was followed across London to Kensal Green Cemetery by thousands of supporters marching behind flags and banners, and though Chartism was by now in terminal decline, as many as 50,000 people were reported to have turned out to say their farewells.

It was not the only great public send-off for a former Chartist leader.

As recently as 1869, 100,000 men and women had lined the streets of Manchester to see the funeral procession for Ernest Jones make its way to Ardwick Cemetery. Though still politically active, and at the time of his death a Liberal candidate for election to one of the city’s parliamentary seats, Jones had earned his political reputation as the leader of the post-O’Connor socialist left-wing of Chartism.

William Lovett’s final journey, however, was to prove somewhat less flamboyant.

There is no newspaper account of whatever funeral cortege there may have been, though it seems most likely that it would have carried Lovett’s body along the more-or-less straight road that runs up from the Euston Road through Somers Town, Camden and Kentish Town to Highgate Cemetery, where, according to the Islington Gazette, “he had often expressed a wish to be buried” (15 August 1877).

There, according to all reports, after the minimum permitted religious service (Lovett had abandoned his Methodist faith decades earlier), “a number of friends who had known and loved this former leader in the political and social contests of the century gathered round the grave to hear a few words from some of his friends”.

George Jacob Holyoake, the secularist and co-operator, recalled Lovett’s contributions to the radical cause stretching back to the 1820s, when he had run the first co-operative store in London, through his days in the Chartist movement and on through his work promoting secular education.

“He was a man prompt on the platform, ready with his pen, careful of details essential to political business, and gave influence to his principles by his high character, his independence, intelligence and personal integrity. He advanced his principles as much by his life as by his labours,” declared Holyoake.

G E Baggis, described by the Islington Gazette as “an old fellow-labourer”, added that Lovett was a man who won the respect of all by the purity and earnestness of his life.

And with that, the service was over.

Those listed as having been present included Miss Eliza Meteyard, a journalist and author who wrote under the name ‘Silverpen’; the secularist and soon to be MP Charles Bradlaugh; John Passmore Edwards, also soon to be elected to Parliament; and perhaps 20 other people. Others reported to have been there included: Mr Runtz, Mr Howard Evans, Mr Henry Moore, Mr Richard Moore, Mr Henman, Mr Matthew Allen, Mr Truelove, Mr W.S.Burton, Mr Constantine (Manchester), Mr Corfield, Mr Lovett King, and Mr Ashley. Of the vast crowds and ostentatious mourning that had been a feature of earlier Chartist funerals there is no mention.

The following month, a heartfelt tribute from George Julian Harney, then living in the United States, would appear in the trade union newspaper The Bee-Hive (8 September 1877). In it, Harney spoke of receiving a letter from Lovett that May in “the same clear, neat and firm ‘hand’ that was his when, still under forty years of age, he penned the minutes and documents of the National Convention”.

Putting old divisions aside, and lamenting that Chartism had ever fallen into “sections”, Harney attributed the People’s Charter to “the outcome of his brain and the work of his hand”, and recalled that Lovett had served a year in prison for his part in the movement.

Besides mourning the loss of a fellow delegate to the First Chartist Convention of 1839, he dropped broad hints that Lovett’s wife should be financially supported.

In pointed terms, Harney talked of Lovett’s many friends in London, his “private circumstances” (that is, Lovett’s poverty), and his reluctance “to offer any suggestions” as to the support they might offer Mary Lovett, his “excellent and honoured wife, the cultivated, patient and heroic partner of his joys and sorrows, his help-mate to success, his sustainer in times of disaster and discouragement”.

The contrast between the funerals of Feargus O’Connor and William Lovett could not have been more marked. And yet in death these two events reflected the personalities and the political approaches that the two men had epitomised in life: O’Connor’s, brash, populist and demonstrative; Lovett’s quiet, thoughtful and serious.