A Chartist broadside ballad

Crudely printed on cheap paper and often sold for a penny a time, broadside ballads were quick and easy to produce and could get the lyrics of a new song out to a popular audience in no time. Though often written as drinking songs and dealing with timeless issues of love and personal rivalries, they could also take a political turn, dealing with the controversies and personalities of the day.

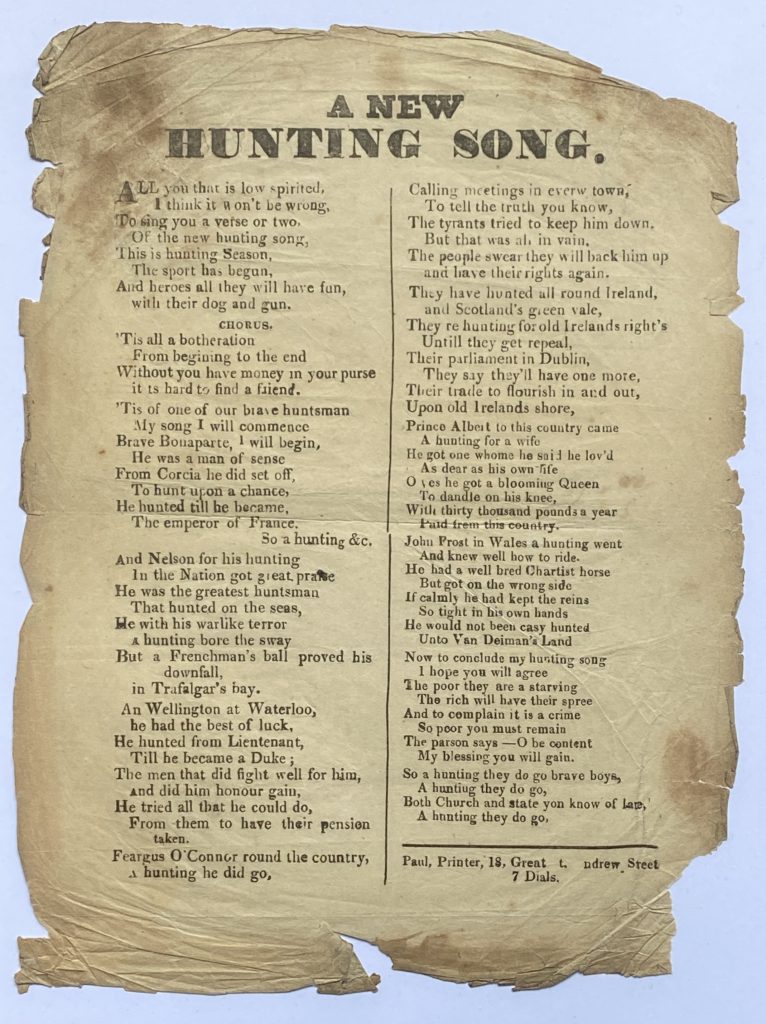

The broadside ballad sheet shown here was one such: broadly radical in tone, lauding Napoleon Bonaparte as ‘a man of sense’, and attacking both the Duke of Wellington and Prince Albert, it has two specifically Chartist verses, one praising the Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor, the other rather more ambiguous in its account of John Frost and the Newport Rising of 1839.

Around 10 inches by 71/2, browned, creased and damp-stained, the broadside is badly damaged around the edges, but fortunately its wide margins have ensured that the text is largely unaffected. It was printed by ‘Paul’ of ‘7 Dials’. Though part of the address has been lost, this would be Charles Paul, a prolific publisher of broadside ballads who worked from 18 Great St Andrew’s Street (now the northern half of Monmouth Street running from Seven Dials towards Neal Street and Shaftesbury Avenue in central London). Seven Dials was at the heart of the notorious parish of St Giles, famously or infamously depicted in William Hogarth’s Gin Lane, and in August 1848 it was a mustering point for Chartists and Irish Confederates ahead of the thwarted rising which planned to seize London. There would have been plenty of potential customers for such a ballad – provided they could find the small sum needed to buy it.

A New Hunting Song, at least in this format, probably dates from the mid 1840s as Chartism’s popularity waned rapidly after 1848.

The first Chartist verse reflects Feargus O’Connor’s apparently never-ending speaking tours and the numerous appearances at public meetings that helped cement his image as a Chartist leader:

‘Feargus O’Connor round the country,

A hunting he did go,

Calling meetings in every town,

To tell the truth you know,

The tyrants tried to keep him down,

But that was all in vain,

The people swear they will back him up

and have their rights again.’

The second Chartist verse concerns John Frost, one of the leaders of the Newport Rising, who had been transported to Van Diemen’s Land (later Tasmania). A great petitioning campaign in 1841 and continuing efforts to have him pardoned kept his name very much in the public eye:

‘John Frost in Wales a hunting went

And knew well how to ride.

He had a well bred Chartist horse

But got on the wrong side.

If calmly he had kept the reins

So tight in his own hands

He would not be easy hunted

Unto Van Deiman’s Land’

Generically titled A New Hunting Song, the ballad was almost certainly intended to be sung to an already well-known tune of that name. This was a common practice, ensuring that the new lyrics could be easily become part of the popular repertoire. In this case, it seems that many of the words would also have been familiar: at least three other versions of the ballad can be seen in the Digital Collections of Trinity College Dublin, all apparently dating from around the same period.

The first shares the same verses on Nelson, Wellington and Albert with the Chartist version, but concludes with two specifically Irish verses – the first lamenting the loss of the Irish Parliament (as a result of the Act of Union in 1800) and the second in praise of Daniel O’Connell, known as the ‘Irish Liberator’, a popular Irish radical but no friend of Chartism.

The second version is also obviously Irish in origin. Though many of the lyrics are different, the title and the metre are the same as the Chartist New Hunting Song. This variant includes a verse naming Feargus O’Connor and the ‘80,000 sportsmen’ prepared to join him in the field, ‘with spears so bright they seek their right and make the tyrants yield’. It concludes with a call for the repeal of the union.

A third version, titled A New Hunting Song on the Eastern Question, shares none of its lyrics with any of the other three, but once again its title and metre suggest a common tune. Its theme is the increasing tension with Russia, not least over India, and suggests that Irishmen are ready to fight. It would not be long till they were called on to do so at the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1853.

The New Hunting Song was not the only Chartist broadside ballad. Jennifer Reid, an expert on broadside ballads, performed several at Chartism Day 2023, including Shabby Feargus, which features as a video in the Society for the Study of Labour History report of the event. Others can be found through the Broadside Ballads Online collection at the Bodleian Libraries, some of which were printed by Charles Paul and other Seven Dials printers.

One ballad, printed by Paul and titled The Chartist Flare-up on Whitsun Monday, recounts the clashes between Chartists and police after the rejection of the third Chartist petition in 1848. In vivid language that comes close to reportage for the benefit of those who had not been there, it reads:

‘You would laugh to see the people roam,

When they at night are going home,

With broken hats and bonnets too,

Some tare their coats, some lost their shoes,

Teeth knocked out as some supposes,

Besides black eyes and bloody noses,

Some lost their shawls and some their riches,

And some had their shirts hanging out of

their breaches’

Other ballads specify the tune to which the Chartist lyrics are to be sung: The Chartists are Coming to the tune of The Bailiff is Coming; The Chartist Song to the tune A man’s a man for a’ that; and Peggy Potts’ speech to the poor folks, at Sunderland election to Barbara Bell.

Though it gives no indication of the tune, perhaps the bawdiest broadside ballad in the collection (again a product of Charles Paul’s printworks) is The Gutta Percha Staff, or, The Adventures of a Special Constable, which mocks the special constables signed up to police the Chartists in 1848 through the story of one such volunteer who turned out to be easily distracted by ‘a pretty servant girl’ and her interest in his ‘gutta percha staff’.

‘When she had satisfied herself,

That it was not made of wood,

If I was poked about with it,

I’m sure it would do me good.

He poked her here, he poked her there,

Untill he made her laugh.

I am ready for another poke

With your gutta percha staff.

The broadside ballad reproduced on this page is in the collection of Mark Crail, who runs the Chartist Ancestors website.