Thomas Martin Wheeler, 1811 – 1862

An Owenite socialist, Chartist journalist, author and organiser, Thomas Martin Wheeler was at the heart of the Chartist movement throughout the 1840s, and went on to build one of Britain’s biggest mutual societies. This is his life story.

Thomas Martin Wheeler was at the centre of Chartism’s highs and lows for nearly twenty years. As London correspondent for the Northern Star, secretary to the National Charter Association, director of the land company and for a time a smallholder at O’Connorville, he was an ever-present figure at conferences and conventions, and a committed supporter of Chartist newspapers.

Wheeler was no great orator, and unlike many of his contemporaries was never imprisoned for his activism. But while his time was increasingly taken up in the 1850s running the Friend in Need Life and Sick Assurance Society, in 1858 his earlier support for the Chartist press was unexpectedly to land him in gaol. Struggling to pay the bills for his People’s Paper in 1853, Ernest Jones had persuaded Wheeler to stand surety for a commercial loan of £50 intended to help with cash flow. Five years later, Jones defaulted on the loan having paid off just £10, and the lender pursued Wheeler for the balance, plus interest and legal costs. Unable to pay, he was committed to the Whitecross Street debtors’ prison.

Wheeler and Jones had gone their separate ways politically even before the loan arrangement, but Wheeler had remained active in supporting the paper as best he could throughout the final years of Chartism. Despite this, Jones made no effort to help Wheeler, and it was only thanks to his friends that the money was found to free him. It was an unhappy end to two decades of Chartist activism, but only a small episode in a busy if not long life.

Before Chartism

Thomas Martin Wheeler was born on 23 November 1811 at Lock’s Fields, Walworth in south London, where his father Joseph, a wheelwright by trade and a supporter of the radical MP Major John Cartwright by politics, ran the King’s Arms public house. At the age of seven, Wheeler was sent to a boarding school in Walton-le-Dale, Lancashire, which he seems to have enjoyed. Though he did not stay long, when he returned to London, his parents (by now running the Prince of Orange in Strutton Ground, Westminster) sent him to continue his education at a school in Stoke Newington, where he stayed until he was fourteen.

Wheeler had trouble finding his niche in the world of work. He was by turns apprenticed to his uncle as a woolcomber and haberdasher in Banbury, and as a baker, working in at least half a dozen shops in London, Berkshire and Oxfordshire before abandoning the work as ‘irksome’, to quote his biographer, and trying his hand as a gardener.

Wheeler had married at Henley on Thames in 1836 while on his travels. His wife Ann (Allder) was ‘a young widow of respectable family’ four years his senior, and they soon had a baby daughter, who they called Frances. Together they settled at Kensington in West London, where Wheeler came into contact with supporters of the socialist and co-operator Robert Owen. They persuaded him into yet another career change, and at the age of twenty-eight he opened a school at 2 King Street, Kensington.

Wheeler’s schoolroom swiftly became the venue for an Owenite social institution, hosting lectures, dancing classes and discussion meetings, while Wheeler himself enrolled as a member of the Universal Society of Rational Religionists. He was also an enthusiastic supporter of the People’s Charter, and for a time his schoolroom hosted both Owenite Socialist and Chartist meetings.

Chartist organiser

The Owenites and Chartists soon fell out. The Owenites branded Wheeler a Chartist and a ‘bad man’ and the political course of the rest of his life was set. In 1840, Wheeler accepted Feargus O’Connor’s offer of a job as London correspondent for the Northern Star, and he was able to combine this with an unpaid role as secretary to the Metropolitan district of the National Charter Association. Now living with his wife and daughter at Mills Buildings in Knightsbridge, he became a popular lecturer at London Chartist meetings, and in 1841 was elected to the NCA’s national executive.

That Christmas eve, the story of Thomas Martin Wheeler almost came to a premature end. He and Ann were traveling by train to visit friends at Reading, but heavy frost had caused subsidence, and the speeding locomotive was derailed. ‘Down into this chasm dashed the swift train, crushing to fragments two of the carriages, smashing others, wounding and maiming sixty passengers whilst thirteen were killed on the spot,’ as his biographer puts it.

Thomas and Ann were missed in the initial rescue operation, but a man who had earlier recognised Wheeler raised the alarm and insisted on a further search. Eventually, the couple were found, ‘embedded in earth and luggage, and, to use the words of Mrs Wheeler, they had literally to be “dug out”.’ Ann, who had been pregnant, lost their baby, and Thomas would suffer from the effects of the accident for the rest of his life.

On the national stage

In 1842, Wheeler was present in his capacity as a Northern Star journalist at the Convention called to present the ‘leviathan petition’ to Parliament. He continued to speak at meetings across London, including at an Anti-Corn Law League event in Deptford where he and other Chartists forced their way onto the platform and had Wheeler elected to the chair. The Chartist Peter Murray McDouall was arrested soon after the meeting, and warrants were issued for the arrest of Wheeler and others, but not carried into effect.

That autumn, in the wake of the general strike wave that had swept the North of England, numerous Chartist leaders were arrested, among them Feargus O’Connor, the Star’s editor William Hill, and John Campbell, the NCA general secretary. Wheeler and other London Chartists now stepped up to establish an emergency NCA executive with Wheeler as general secretary.

Wheeler’s role was supposed to be a temporary measure. But in the coming months, William Hill and others began to raise doubts about the NCA’s finances. In the bitter dispute that followed, Campbell refused to make the organisation’s account books available for audit, or to return them when in 1843 he resigned and swiftly left England for a new start in the United States. Wheeler was the obvious candidate to succeed him.

O’Connor made plain to Wheeler that he must choose between a paid job with the Northern Star and a paid job with the NCA. Wheeler chose the NCA. As his biographer noted: ‘The office of General Secretary to the Chartist body was not a sinecure; independently of the labours involved in appointing and paying the lecturers of upwards of forty districts of the metropolis, Wheeler had to answer the whole of the correspondence which came in from all parts of the kingdom to his office, 243½ Temple Bar. In all matters in which advice was needed by his country friends, to him they appealed; and when any of them came to London respecting strikes or other trade matters, they at once made their way to Wheeler’s residence; in fact, his office was a club-room to the politicians of the working classes.’

The land

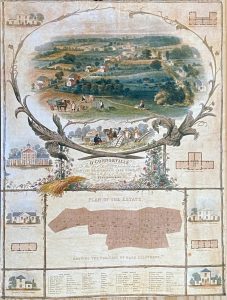

In 1845, a National Charter Association convention at the Parthenium Assembly Rooms in St Martin’s Lane, London, approved Feargus O’Connor’s land plan. Wheeler had been interested in land ownership since his days as an Owenite gardener, and he now became secretary of the land company and, in 1846, chief clerk to a new land bank. He stepped down as general secretary of the NCA, but with so much of the movement’s money flowing through his hands, there were accusations of financial mismanagement. Although cleared of any wrongdoing, Wheeler resigned from all his posts and retired to run the two-acre smallholding he had been allocated at O’Connorville.

Describing a later visit, Feargus O’Connor wrote: ‘Wheeler’s house is the first you come to, and I was literally astounded when I beheld its neatness and its beauty. In front, he had erected a neat little verandah, and all around, for a considerable space, were the most luxuriant dahlias, sunflowers and shrubs, while the interior was a picture of simple neatness’ (NS, 6 November 1848).

Wheeler returned to front-line Chartist politics in 1848, when he took part as a delegate in the National Convention called to oversee the third great petition for the Charter. And on 10 April, he was among those on the front seat of the first wagon at the head of the procession to the monster meeting on Kennington Common, along with Feargus O’Connor, Christopher Doyle, Philip McGrath, Ernest Jones and George Julian Harney. The O’Connor loyalist and Leeds Chartist William Rider would later credit Wheeler with averting a confrontation with the authorities that day.

Wheeler returned to his quiet life in the country, but gardening and occasional interventions in the local vestry politics evidently lost their hold on him. In 1849 he wrote his semi-autobiographical novel Sunshine and Shadow (now much studied as an exemplary work of Chartist fiction), and in 1851, as the land company slid into difficulties, he returned briefly to his old role at its head. Wheeler also took on the running of Ernest Jones’s new People’s Paper, guaranteeing a substantial loan on behalf of its editor; but within a matter of months he and a dozen other members of the shareholders’ committee had resigned over Jones’s management of the funds. It was not until years later that Wheeler would suffer the consequences.

The Friend-in-Need Life and Sick Assurance Society

With Chartism now close to extinction, in 1852 Wheeler turned his talents as an administrator to a new job as metropolitan manager of the newly formed British Industry Association, which offered life assurance to working-class subscribers. He left after nine months, but had found a new outlet for his energies – one that promised, for once, a financially comfortable future.

The Friend-in-Need Burial Institution had been founded in Whitechapel as far back as 1831, and had achieved little in twenty years. John Shaw, an old Chartist ally of Wheeler’s who was also the Friend-in-Need’s President, brought his old friend in to oversee a transformation in its fortunes. Wheeler argued that as a purely local organisation based in a poor part of London, the Friend-in-Need was unable to ‘obtain a fair average of the lives of those they assured’, and advocated turning it into a national body – able, in effect, to help subsidise its payments to poorer and shorter-lived members through the subscriptions of its wealthier and longer-lived members outside the East End.

With Thomas Martin Wheeler as acting manager and secretary, John Shaw as metropolitan manager, and George William Wheeler (Thomas’s brother) as provincial manager, the Friend-in-Need took on a new life. The old burial club now added insurance against sickness and the many other calamities that threatened the life and well-being of Victorian workers to its portfolio, and began a rapid expansion. In 1857, the Friend-in-Need took over the National Assurance Friendly Society set up by Thomas Clark, one of Wheeler’s former critics in the land company days, and its future was secured. Within a few short years the Friend-in-Need Life and Sick Assurance Society had become one of the largest such firms in the country.

Clark died soon after the takeover, in March 1857, and Shaw succumbed to consumption later in the summer; but the Friend-in-Need flourished moving to large new offices at 147 New Oxford Street. Here, in August 1860, Wheeler’s employees presented him with ‘a most splendid and artistically decorated papier mâché writing desk’. The names of Christopher E. Ruffy, son of Daniel William Ruffy, another former Chartist turned life assurance company secretary, and former O’Connor loyalist William Rider were among those whose names were inscribed as contributors to the gift.

The following summer, says his biographer, Wheeler found that ‘the active and restless life he had lived began to tell upon his small, yet sinewy frame’, and he spent months away from work with his wife Ann to recuperate. It was clear, however, that his health was failing, and he suffered what may have been a heart attack. On 16 February, he ‘had a relapse of the attack in his chest, which induced bronchitis’, and died at home with his daughter Frances, now Mrs Tredrea, and friend John Bedford Leno at his bedside. He was just fifty years old.

Wheeler was buried at Highgate Cemetery on 24 February 1862. That day all business at the office was suspended. The hearse, drawn by four horses, was preceeded by two mounted horse porters with pages carrying feathers, and followed by twenty coaches filled with mourners – family, friends, and numerous old Chartist comrades among them.

Notes and sources

The small photograph of Thomas Martin Wheeler on this page is pasted to a memorial card which commemorates his role in founding the Friend in Need Society. It carries his signature, but this is clearly printed as it also includes the date of Wheeler’s death. The card is in the collection of Mark Crail, who runs the Chartist Ancestors website.

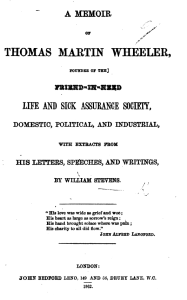

A Memoir of Thomas Martin Wheeler, Founder of the Friend in Need Life and Sick Assurance Society With Extracts from his Letters, Speeches and Writings, by William Stevens (John Bedford Leno, 1862). Available via Google Books (accessed 1 January 2024).

Sunshine and Shadow: A Tale of the Nineteenth Century, by Thomas Martin Wheeler (1849)