William Rider, 1804 – ?1865

Unwavering in his loyalty to Feargus O’Connor and unbending in his commitment to physical force Chartism, William Rider was a working-class activist who became publisher of the Northern Star.

William Rider was born in Leeds in 1803 or 1804,1 and was long established as a radical organiser in the town some years before the advent of Chartism. He first came to public notice towards the end of 1831 when the Leeds Patriot and Yorkshire Advertiser reported his speech at ‘a meeting of operatives’ at the Sir John Falstaff inn in St Peter’s Square called to form the Leeds Radical Political Union (19 November 1831, p3). Rider was soon elected to serve as its secretary.

The Union was hostile to the Whig Reform Act then before Parliament, warning presciently that it would lead a newly enfranchised middle-class into alignment with the established ruling class, thus isolating and excluding the working class from political power. But the organisation’s primary practical focus was on supporting the ten hours movement as it sought to restrict children’s working hours and improve conditions in the factories and mills.

Rider became known for his scathing attacks on his political opponents, interrupting Thomas Babington Macauley’s speech at the Coloured Cloth Hall Yard when the historian was drafted in by local Whigs as a candidate in the 1832 general election, and in 1834 publishing The Demagogue, a viciously written spoof claiming to be the autobiography of Edward Baines, factory manager, editor of the Leeds Mercury and MP for the town, whom he dubbed the ‘veracious poison-monger, Baines’. Rider was also, not surprisingly, an opponent of the New Poor Law of 1834.

Despite his strong opposition to factory-owning Whigs, however, Rider evidently got on well with the Tory radical Richard Oastler, whose views on factories and workhouses aligned with Rider’s. Years later, Oastler would ask George Julian Harney to ‘remember me kindly to my old friend Rider’2

Chartism and the First Convention

With the growth of working-class radicalism in 1837, Rider became secretary of the new Leeds Working Men’s Association, serving alongside Joshua Hobson, soon to be publisher of the Northern Star. Along with Feargus O’Connor, he was also instrumental in organising the Great Northern Union the following year, subsuming the Leeds and other working men’s associations within it as a working-class counterweight in the North to the middle-class reformers of the Birmingham Political Union and what he dubbed ‘the self-elected London adventurers’ of the London Working Men’s Association.

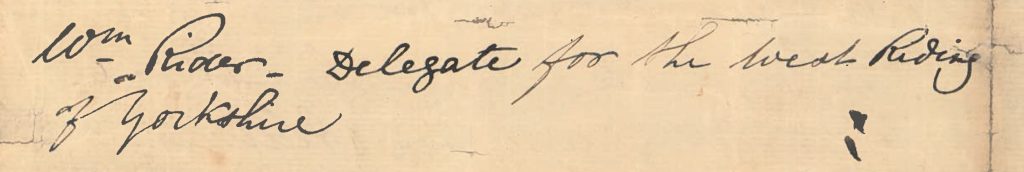

On 15 October 1838, a monster meeting on Hartshead Moor, a huge natural amphitheatre easily accessible from Leeds, Bradford, Huddersfield and Halifax, elected Rider, O’Connor, Peter Bussey, Lawrence Pitkeithley and James Paul Cobbett as the West Riding delegates to the proposed General Convention of the Industrious Classes. More commonly known as the First Chartist Convention, it met in London on 4 February to oversee the presentation of the first Chartist petition and to decide on what to do next.

Although the convention dragged on into September following Parliament’s refusal even to hear the petitioners, Rider did not stay long. In a rare split from O’Connor’s position, he tried to get the convention to call on the People to arm, but failed. Back in Leeds, speaking at an open air meeting on Easter Monday, 1 April 1839, he warned: ‘The citadel of corruption cannot be taken by paper bullets. There is a crew … called physical force men who are trying for something more than argument. It is this that makes the Whigs and Tories tremble.’ But no matter how popular this view might have been among his constituents, it did little to convince his fellow delegates.

Rider resigned from the convention on 2 May, and at a mass meeting on Peep Green in July 1839 declared that ‘there were not eight honest men in the Convention’. Unlike many of those who stayed on, however, he escaped arrest that summer.

Rider became associated with the Leeds Total Abstinence Charter Association, his name listed as one of the organisers of a public tea party planned for New Year’s Day 1841 (NS, 5 December, 1840). His address was given as 67 Lemon Street, in the Quarry Hill area, and both he and his wife Elizabeth were still there that June when the census was taken.

Working for the Northern Star

The date on which William Rider joined the staff of the Northern Star is not recorded. However, he was well established as assistant clerk by May 1841, when he can be found hectoring the London Chartist Charles Neesom over his ignorance of the mechanics of newspaper publishing (NS, 6 May 1841, p6). The role placed him under John Ardill, keeping the paper’s accounts and managing its day-to-day business affairs.

When Feargus O’Connor relocated the Northern Star from Leeds to London at the end of 1844, Rider seems to have gone with it. Those wanting to advertise in the paper after that date were regularly advised in its pages to write to him at the Star’s new print shop in Great Windmill Street, Haymarket. And when O’Connor fell out first with his editor Joshua Hobson and his clerk John Ardill, Rider had no hesitation in siding with the Chartist leader. At a meeting in Manchester, O’Connor accused both men of defrauding him, the Northern Star and the Chartist movement (NS, 30 October 1847, p1). He then introduced Rider to those present as the paper’s new clerk in place of Ardill.

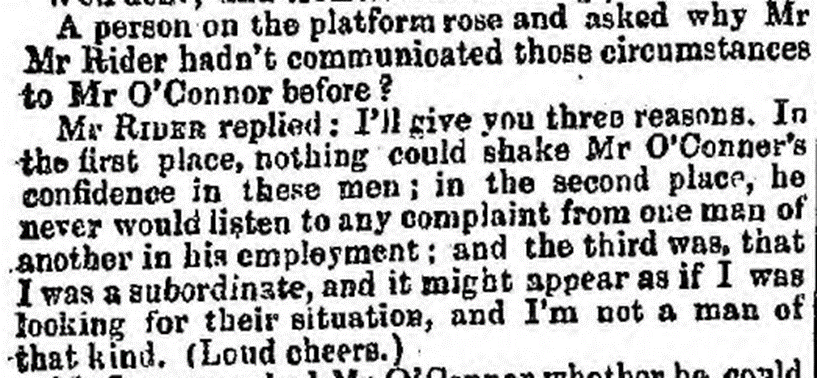

Ever loyal, Rider repeated O’Connor’s allegations, and went further to claim that Hobson and Ardill had systematically cooked the books since the paper’s inception a decade earlier. Claiming that he had been aware of this all along, he said he had failed to mention it previously because he knew that O’Connor had confidence in both men (NS, 6 November 1847, p3-4). The bitter dispute would carry on into the new year, and eventually cost O’Connor several hundred pounds in damages for libel.

Following his promotion, Rider appears to have steered clear of political controversy to concentrate on his duties at the Northern Star, and from its issue of 14 October 1848, he became its publisher. Though this might appear to be a second step up, it was one which may have been intended to save O’Connor part of the wages bill as the paper had failed to keep the extra readers who had helped raise its circulation in the excitement of that year’s brief Chartist revival. Rider was also kept busy overseeing the Defence Fund on behalf of those arrested in 1848. This seems to have been hard going: ‘Chartists, – do cast your eyes at the enormous (?) amount sent weekly to the Defence Fund!’ he wrote with typical sarcasm ‘When will Mr Nixon get paid, and Mr O’Connor repaid? Let us hear of a few Soirees for that purpose. I am paying £1 5s weekly to exempt prisoners from oakum picking OUT OF THE NORTHERN STAR – out of Mr O’Connor’s purse’ (NS, 17 February 1849, p1). Rider had good reason to be angry at the shortage of funds for this purpose: later that year two London Chartists would die in prison after refusing to carry out prison work and being punished for it.

Throughout this time, Rider’s address is given as 5 Macclesfield Street in the parish of St Anne’s Westminster (now at the centre of London’s Chinatown in Soho). He was evidently still living here when, in its issue of 19 March 1851, the Northern Star carried the following brief notice: ‘DEATHS. On Saturday morning last, after a protracted illness, Elizabeth, the wife of William Rider, Publisher of this paper.’ Days later, when the census took place on 29 March, William Rider ‘Clerk Publisher’ could be found at home with his nine-year-old granddaughter Elizabeth Downs. Rider seems to have remarried very soon afterwards, however. The marriage of a William Rider, widower, and Sarah Reed, a widow born in Oxfordshire, took place at St Michael’s in Burleigh Street near Covent Garden on 22 June 1851.

Rider continued to publish the Northern Star until 13 March 1852, after which, with the sale of the paper to George Fleming, his name disappears from its pages for good. Many years later, Thomas Frost in an article on ‘The Life and Times of John Vallance’ for the Barnsley Times (29 July 1882, p3), wrote that he did not know what had become of Rider after the cessation of the Northern Star, but added: ‘O’Connor left him a small legacy out of the little that remained of his property’.

But while Rider ceased his active involvement in politics in 1852, he certainly had not disappeared. Neither would he have benefited greatly from O’Connor’s generosity: after the Chartist leader died in 1855, his estate was valued at less than £20.3

Life after Chartism: ‘I still hold to the same doctrine’

The former London correspondent of the Northern Star Thomas Martin Wheeler had taken over the highly successful Friend in Need Life and Sick Assurance Society in 1852, and his staff included a number of former Chartists. Among them was William Rider, who in 1860 was one of a number of clerks at the company to present Wheeler with a writing desk. His experience handling the finances of the Northern Star and Chartist defence funds evidently helping him to a new career. And he still lived in Soho: the 1861 census found William Rider, ‘accountant, clerk’, and Sarah Rider at home at West Street.

After Wheeler’s death in 1862, his biographer Wiliam Stevens turned to Rider for help with his life story. Rider paid tribute to Wheeler’s work on behalf of the Northern Star and is thanked for his assistance. But this was not to be his only contribution to the safeguarding of Chartist history. When Robert Gammage published the first edition of his History of the Chartist Movement as a book in 1855, it included the summary of a letter sent to him by Rider ‘containing some explanations and denials’ (Appendix A). This must have been sent after the History appeared in serial form the previous year.

In it, Rider (who Gammage names both as Rider and Ryder, though he himself never seems to have spelled his name with a Y) explains his views on physical force: ‘For thirty-five years I have belonged to the same school, and still believe it to be the bounden duty of every man to possess arms, and to learn their use; but while propounding this doctrine, I have invariably opposed partial and premature outbreaks, contending that a want of unity incapacitated us from compassing our object and that we lacked this unity consequence of man-worship; and the treachery and bickerings of self-constituted leaders, and idle adventurers. I repeat that I still hold the same doctrine of necessity of man being armed and trained to enable him to cope with domestic enemy, or foreign foe. I never thought your moral force, your rams horns, or your silver trumpets would level the citadel of corruption.’

Rider lost none of his radical fire with age. In 1864, he contributed a lengthy letter to the Miner and Workman’s Advocate attacking coal owners who opposed education initiatives (17 December 1864), following it up the following month with another on political rights, in which he argued: ‘Certain lickspittles may prate about the laws of this country being impartially administered; but the laws are so framed that wealth will enable a lawyer to discover many loop-holes for the escape of a long-pursed client, while not a crack can be perceived for the admission of the least ray of hope for the man whose pocket is unfortunately lean’ (28 January 1865).

The following week, the paper’s editor lamented the ‘havoc death has made among the Reformers of our time, especially among those connected with the Chartist movement’, but he was heartened to be able to report that William Rider, ‘still clear-headed and strong’ contributed occasionally to the paper (18 February, p4). There was to be one more letter, in which Rider wrote that with England now at peace with the whole of Europe, the time had come to disband a few regiments of the line (1 April 1865).

William Rider disappears from public life at this point. Though still only just into his 60s, he probably died soon after this final letter. He may be the William Rider buried at West Brompton Cemetery in May 1865, or the William Rider whose death in the Strand district appears in the civil register in the second quarter of 1869. Or one of a number of other William Riders who died in this period.

Notes and sources

1. Though William Rider is a common name, and a number of William Riders were born and baptised in Leeds around that year who could equally well be him, his date of birth can be verified from the census records for 1851 and 1861.

2. Letter, June 4 1849, The Harney Papers, edited by Frank Gees Black and Renee Metivier Black International Institute of Social History, 1969).

3. The financial downfall of Feargus O’Connor on the Chartist Ancestors blog (9 March, 2023), accessed 12 February 2024.