William Cuffay, 1788 – 1870

William Cuffay was a leading London Chartist, the son of a black former slave, he was an activist in the tailors’ trade union before his involvement in Chartism, and went on to play a major part in the movement before being transported to Tasmania in 1849.

Born at Old Brompton in what is now Gillingham in Kent, William Cuffay was one of five children born to Chatham Cuffay, a black former slave from St Kitts who worked at Chatham dockyard, and Juliana Fox, a locally born white woman. Baptised at St Mary’s, Chatham, on 6 July 1788, he was apprenticed to a tailor, and found work in his home town before moving to London in 1819.

Cuffay (sometimes spelled Cuffey or Cuffy, though not by him) was disabled: he had been born with deformities to his legs and spine, and as an adult was just 4 ft 11 in (1.50 m) tall. He was one of around 10,000 black people thought to have lived in London at this time (though figures are difficult to establish with certainty). And though both his disability and his colour would later earn him the scorn of establishment newspapers, Cuffay himself appears to have been undeterred from playing a prominent public role: by all accounts a good singer who often performed at Chartist social events, he also became a powerful public speaker and was prominent through his activism and leadership not just in Chartism but in his trade union.

Cuffay was married three times. His first marriage to Ann Marshall took place at St Martin’s in the Fields in May 1819; however, Ann died in 1824. He subsequently married Ann Broomhead in February 1825, but she too died in April of the following year, in childbirth. Their daughter, Ann Juliana Cuffay, was baptised in Gillingham, but died soon afterwards. Cuffay married for a third time on 31 May 1827 at the church of St James, Picadilly. His wife, Mary Ann Manvell, was a straw-hat maker, and after living for a time in Lambeth, they made their home at 409 The Strand – then as now the main road joining Westminster to the City of London.

Tailor and trade unionist

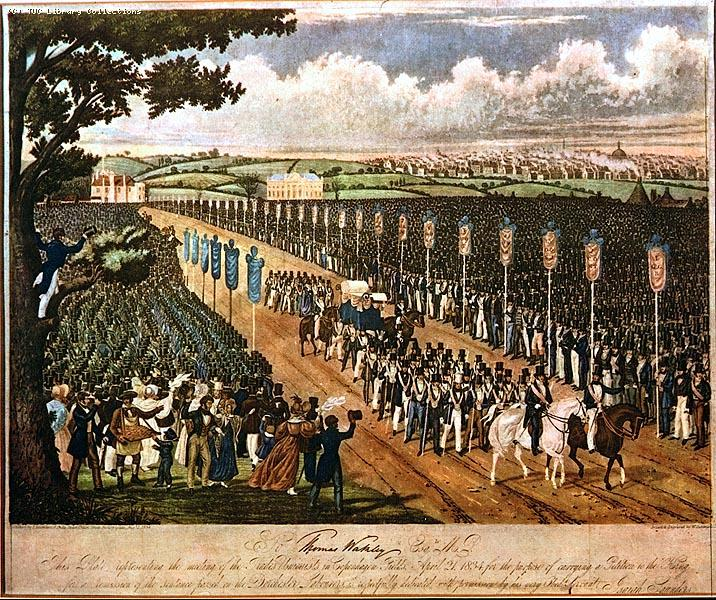

As a working ‘flint’, a journeyman who had served his apprenticeship, Cuffay must have been well known among London’s tailors. This was a notoriously political trade, and in Cuffay’s day included the likes of Francis Place, who in the 1820s played a significant part in getting the anti-trade union Combination Acts repealed, and Robert Wedderburn, a British-Jamaican radical strongly influenced by Thomas Spence who became a free-thinker and served several prison terms. Cuffay, however, only came to prominence in 1834, when a massive strike by London tailors followed close on the heals of a great demonstration in the capital in support of the transported Tolpuddle labourers.

Cuffay did not join the strike when it began on 28 April, but was soon persuaded to do so. When the strike ended in June, the union’s funds exhausted, and many forced back to work by the threat of transportation for those who stayed with the union, Cuffay was among those who refused to sign the masters’ ‘document’ and found themselves out of a job. The failure of the strike broke the tailors’ power, with ‘flints’ increasingly replaced by untrained ‘slops’ working in sweated conditions for low pay.

Cuffay the Chartist

Cuffay must have remained active in the tailors’ union. But his name does not appear in the public record again until late 1839, when he is reported to have chaired a meeting of the Metropolitan Tailors’ Charter Association (The Charter, 13 October 1839, p606). Some weeks later, after the suppression of the Newport Rising, he moved a resolution at a meeting of the same body in sympathy with those involved and protesting at the ‘cruel, unjust and vindictive treatment’ of imprisoned Chartist leaders. This meeting was also reported in The Charter (1 December 1839, p713) and took place at the Charter office in Catherine Street, just off the Strand: the capital’s tailors were an integral part of London’s Chartist movement, and it seems likely that Cuffay would have been a Chartist from the start.

Cuffay maintained his involvement in Chartism. In 1841, when the London tailors affiliated to the National Charter Association, he was one of three nominated to serve on the general council (Northern Star, 18 September 1841, p2). Cuffay was also elected to represent his trade (now calling themselves the Tailors National Charter Association) on the Chartist county council for London, and his name began to appear regularly in the Northern Star, either as chair of the tailors’ union or reporting back from county meetings. By the end of the year, Cuffay was well known enough as a Chartist to chair a meeting of the National Charter Association’s general council (NS, 27 November 1841, p8).

Cuffay would, of course, urge his fellow London tailors to support the 1842 petition in support of the Charter, and though not a delegate to the Chartist Convention which oversaw its presentation to Parliament, must surely have been there on the day when carpenters had to be called in to remove the doors from the House of Commons so that the leviathan petition could be carried in.

Later that same year, as a wave of strikes swept the North of England, the National Charter Association’s secretary, John Campbell, and much of the national leadership were arrested, throwing the organisation into crisis. It soon emerged that the NCA’s finances had been badly mismanaged, and amid accusations that Campbell had embezzled the organisation, Cuffay and other London Chartists stepped in to take temporary control and restore stability.

Cuffay was both liked and respected within Chartism, and was recognised as one of the most prominent leaders of the movement in London, along with Edmund Stallwood, Daniel Ruffy Ridley, and Thomas Martin Wheeler. He served as treasurer to the Metropolitan Delegate Council, and both he and Mary Ann were active in raising funds for the Chartist prisoners. The metropolitan delegate committee passed a vote of thanks to Mrs Cuffay for her exertions in organising a lottery which raised between £11 and £12 (NS, 12 November 1842, p2). She wrote back to the committee thanking them and remarking that their comments had ‘almost induced her to overlook the “late hours” which Mr Cuffay alleged “the Charter” to have latterly led him into’ (NS, 14 November 1842, p2).

In view of her comments, it is interesting to note that, when he was elected president of the board of directors of the new Political and Scientific Institution the following year, he also stood down from the Chartist metropolitan delegate committee (NS, 1 April 1843, p2).

‘The immediate descendent of a West Indian slave’

Cuffay was a rare and prominent black figure in Chartism, and his race did not go unnoticed. The Times would later refer disparagingly to Cuffay and the London Chartists as ‘the black man and his party’. Chartism’s own approach to the abolition of slavery in the British colonies, which helped shape many Chartists’ approach to race, was to say the least questionable, and its failure to distinguish chattel slavery from wage slavery problematic. Over time, however, thanks to the efforts of Cuffay and the likes of Northern Star editor George Julian Harney, Chartism would come under the influence of American labour radicals’ anti-slavery ‘free soil’ ideology, helping in turn to shape later British labour support for the Union and abolitionism in the American Civil War.

Cuffay himself was not afraid to draw attention to his colour and to present himself in a positive light. The Sentinel (1 April 1843) recorded his speech at a Chartist meeting in High Holborn

‘Look at him. He was the immediate descendent of a West Indian slave, whose father was an African slave; but he was born amongst them a free man – and he respected, he loved Englishmen, for their great exertions in breaking the chains of the bondmen, and abolishing slavery in their colonies. The people forced that measure, though it cost them twenty millions to do it; and he was grateful to them for it. He would now exert himself in their cause, and assist them to gain their freedom. (Cheers.) He considered them a noble and a generous people and in the name of his fathers and his relations – the slave class of the West Indies and of Africa – he thanked them kindly for what they had done for him, and ever, whilst he had life and reason, he would do his best to aid them in return.’

1848: Kennington Common and the Third Petition

Cuffay was actively involved in the Chartist Land Plan, which aimed to settle industrial workers in Chartist colonies where they might cultivate smallholdings, becoming economically independent and perhaps eligible to vote. It was Cuffay who at the 1845 Chartist Convention moved the resolution to draw up the plan, and he would serve as one of two auditors to the Land Company when it was formed. But in truth Chartism was politically largely inactive in the years after the second petition.

All this would change in 1848, when with revolutions sweeping Europe, Chartism began to stir again. Plans were put in train to organise a third Petition for the Charter to test sentiment in Parliament after a general election the previous year that had seen the Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor elected MP in Nottingham. And Chartist public meetings once more began to draw big crowds.

Cuffay was among the speakers at ‘a tremendous gathering’ at the Circus of the National Baths in Lambeth on 2 March, alongside James Grassby, George Julian Harney, Feargus O’Connor and others where a resolution was adopted warning the British Government against interfering in France. Cuffay welcomed a growing alliance between Chartists and Irish Confederates in England, and warned that this third petition should be the last: ‘The Chartist body should refuse to petition either the Ministers or the Houses of Parliament again either by word or writing’.

Cuffay was among the Westminster delegates elected for the forthcoming Chartist convention, and on 10 April 1848 would have been one of those on the great carriage that led the procession taking the petition to Kennington Common. The intention had been to hold a great rally here before moving on to present the petition to Parliament, as had been the practice in 1839 and 1842.

This time, however, the authorities were determined to ensure this did not happen. The Duke of Wellington was brought out of retirement to mastermind the ‘defence’ of the capital, tens of thousands of special constables were signed up and armed with staves, artillery and cavalry were mobilised in reserve, and public buildings fortified. At Kennington, O’Connor was summoned to meet the Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Richard Mayne and warned that the crowd would not be permitted to march back across the bridges over the Thames, and faced with overwhelming force and memories of Peterloo, he agreed to disperse the crowd.

Cuffay was furious, resisting O’Connor, and from the carriage he ‘spoke in strong language against the dispersal of the meeting, and contended that it would be time enough to evince their fear of the military when they met them face to face’ (Morning Chronicle, 11 April 1848). The whole Convention were ‘a set of cowardly humbugs’, he declared. But his protest was to no avail.

The next day and in the week that followed, Cuffay was back at the Convention. Although he mocked the parliamentary authorities for their claim that the petition had fewer than 2 million signatures, he was also critical of O’Connor’s claim that it had 6 million. Cuffay and Grassby would later make clear that they had warned O’Connor against inflating the number of signatories, but that he had replied that he had already made up his mind to claim 5 million signatories and dismissed their concerns with the words ‘pooh, pooh, pooh; it will never be challenged’. Their warning would not, however, be made public until the end of the year (NS, 2 December 1848, p6).

Conspiracy and conviction

In the mean time, Chartists and Confederates in London continued to meet, to march, and on occasion to clash with the police. And in the wake of mass arrests, an ‘ulterior committee’ of around 30 to 40 delegates began to meet with a view to insurrection. Cuffay took part in his first meeting of the group on 4 August, at Cartwright’s Coffee House in Redcross Street. By 13 August he had been made secretary. The rising was to take place on the evening of Tuesday 16 August, with further risings in Manchester, Birmingham, Bradford, Nottingham and elsewhere. But unknown to the conspirators, there was a police spy named Thomas Powell among their number, and at 6pm that day police raided the Orange Tree pub in Bloomsbury and eleven of their leaders were arrested.

Though not present at the Orange Tree, Cuffay was arrested at home, on the third floor of 11 Holles Street, Wardour Street, two days later. During the arrest, Cuffay was spotted handing a small; ‘pocket pistol’ to Mary Ann. He did not deny it, but argued that he had been ‘threatened with assassination’ and that it was his right to carry it in self defence. When Cuffay came up in court on 20 August, The Times reported: ‘Mrs Cuffey was among the crowd in the body of the court during part of the examination, but having ventured to express her views of the proceeding in too audible terms, she had to be put out by an officer.’

Cuffay and other defendents were moved under armed guard from Bow Street to Newgate Prison, where they were held until trial. Cuffay received a stream of Chartist visitors, giving Thomas Martin Wheeler his scarf as a keepsake; while here, he was sketched by William Dowling, an Irish Chartist – the drawing is the only likeness of Cuffay that survives from his lifetime. Efforts were made to raise money for the wives of those arrested, and Mary Ann was both an active participant in this and a recipient of financial support.

Cuffay came up for trial on 25 September, accused of ‘treason felony’. Although represented by a barrister engaged by Feargus O’Connor, he was swiftly found guilty. Cuffay spoke up to ask for the return of the Westminster Chartists’ blue banner with gold lettering, which he said had been seized during his arrest but belonged to others; this was rejected, but the judge saw no objection to having his letters returned to Mary Ann.

Cuffay was then able to deliver a lengthy speech from the dock in which he said that he had not received a fair trial, and complained of the system of police spies. He went on: ‘I am not anxious for martyrdom, but I feel that, after what I have gone through this week I have the fortitude to endure any punishment your lordship can inflict upon me. I know my cause is good, and I have a self-approving conscience that will be me up against anything, and that would bear me up even to the scaffold; therefore I think I can endure any punishment proudly.’

He was sentenced to be transported to Van Diemen’s Land (later Tasmania) for life.

To Hobart Town

Following his conviction, Cuffay was sent first to London’s Millbank Penitentiary before being transferred to Wakefield House of Correction. By July 1849, he was heading south again, where he was put on board the Adelaide at Woolwich, one of 300 male prisoners bound for Australia. With an additional complement of 50 soldiers under the command of a Captain Deering, four women and eight children, the ship headed to Portland in Dorset before finally setting sail on 17 August.

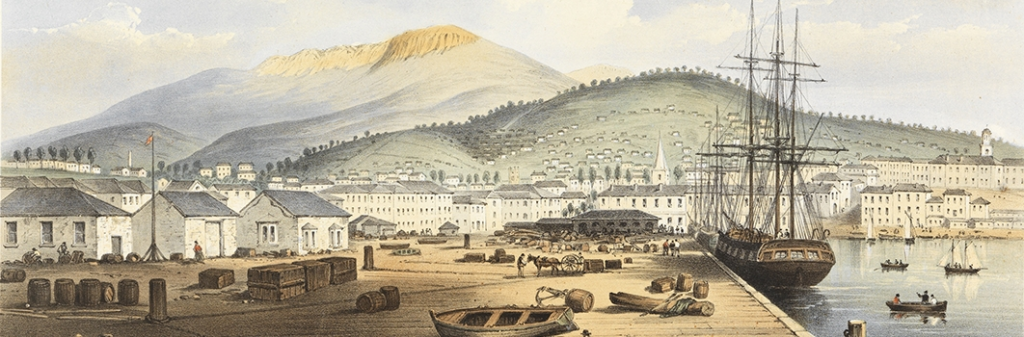

Just 40 prisoners disembarked at Hobart Town (the remainder staying on board to be landed at Port Jackson, Sydney), by which time Cuffay’s name was already widely known locally thanks to press coverage. He had figured prominently in accounts of Chartist activities and trials taken from London newspapers over the previous year, and reports of the Adelaide’s arrival now identified Cuffay ‘the Chartist ringleader’ as being among the newly disembarked convicts.

Unlike many of those convicted of non-political offences, Cuffay was designated a “ticket of leave” man, permitted to work on his own account but expected to attend monthly musters before the magistrates at Hobart penitetiary. He did not go far. Later records have him living at 42 Patrick Street – just 10 minutes’ walk away. He also appears to have found work. And in no time he was already politically active once again: the Colonial Times (28 February 1851) reporting him to be in the chair at a trade union meeting called to demand an end to the use of convict labour in construction work on the docks.

By this time, too, he must have had word from his friends and family in England. The Westminster Chartists sent Cuffay a book of Byron’s poems – which, since the inscription from his former comrades is dated October 1849, after the Adelaide left England, must surely have been sent out to him in Tasmania. Eventually, funded in part by the government and in part by the Medway poor law guardians, Mary Ann Cuffay was reunited with her husband, arriving in Hobart in April 1853.

After eight years in the colony, Cuffay received a free pardon in 1857, the effect of which was to restore all his civil rights.

Throughout the 1850s and 1860s, Cuffay continued his political activities. In particular, he was a vocal opponent of the Master and Servant Act governing the relationship between employers and workers, and campaigned to stop convicts being sent from England. His speeches were infused throughout with the spirit of Chartism and the demand for political rights. Though small in stature and softly spoken, Cuffay appears to have been easily able to command the attention of a crowd in the theatres where political meetings often took place, with newspaper reports frequently recording laughter and applause at his interventions.

In June 1869, Cuffay made his last recorded foray into the politics of Hobart Town, supporting an ally’s nomination for election as alderman. That same year, Mary Ann died.

Cuffay was admitted to the workhouse hospital, Brickfields Invalid Depot, in October 1869. He died there, aged 82, on 29 July 1870. Remarkably for a man who died penniless after a long career as a political outsider, Cuffay’s obituary in the Mercury newspaper was headlined ‘Death of a celebrity’.

The obituary concludes: ‘For most of the time he was at the Brickfields establishment, Cuffey [sic] was an occupant of the sick ward. The superintendent states that he was a quiet man, and an inveterate reader. His remains were interred in the Trinity burying-ground, and by special desire his grave has been marked, in case friendly sympathisers should hereafter desire to place a memorial stone on the spot.’

Remembering William Cuffay

Cuffay never did quite get his memorial stone. At least, not one that directly names him. But in 2000, long after the burial ground closed, a memorial was raised and dedicated ‘to the memory of over 5,000 free settlers and bond convicts buried in these grounds between 1831 & 1872’. It stands today on the edge of the school grounds that now occupy the site.

Cuffay is often referred to as the ‘forgotten’ black Chartist. But this is not entirely the case. His part in the movement was recorded in R.G. Gammage’s near-contemporaneous History of the Chartist Movement (1854 & 1894). He was not one of the twelve leading figures to feature in G.D.H Cole’s Chartist Portraits (1941), but in 1982 John Saville provided entries for him in both the Dictionary of Labour Biography and Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, and Peter Fryer wrote a new version for the ODNB in 2004. William Dowling’s sketch of Cuffay has been in the National Portrait Gallery since 1966, and has since been joined by a portrait by the graphic artist Polyp (Paul Fitzgerald). He features at length in David Goodway’s detailed account of the Orange Tree conspiracy in London Chartism 1838-1848 (1982), in Dorothy Thompson’s investigation of ‘labourers and the trades’ in The Chartists (1984) and in Malcolm Chase’s Chartism: A New History (2007).

Finally, of course, William Cuffay: The Life & Times of a Chartist Leader, by Martin Hoyles (2013) provides a book-length biography of Cuffay which places his life in the contexts of slavery, his trade, his politics, life in 19th century London, and his treatment in the judicial system. And though efforts to get a blue plaque at Cuffay’s old address at 409 The Strand (next door to the Adelphi theatre) did not come to fruition, Medway African and Caribbean Association and the Nubian Jak memorial trust unveiled a plaque honouring both William and Chatham Cuffay in the Historic Dockyard at Chatham in July 2021.

Notes and Sources

Newspaper reports are from the British Newspaper Archive and referenced within the text. After the first mention, those form the Northern Star are given as NS.

Baptismal, marriage and death records can for the most part be found on Ancestry. However, St Mary’s, Chatham, parish register, Medway Archives and Study Centre includes an entry for William Cuffay’s baptism (accessed 8 August 2024).

William Cuffay: The Life & Times of a Chartist Leader, by Martin Hoyles (Hansib Publications, 2013) is the only full-length biography of Cuffay.

Detailed official accounts of the trial of William Cuffay, his transportation to Van Diemen’s Land, and his treatment once there can be found in The Old Bailey Online and Digital Panopticon (both accessed 10 August 2024).

William Cuffay’s poetic gift from the Chartists, by Mark Crail, Chartist Ancestors blog, 6 June 2015 looks at the book of poetry sent by the Westminster Chartists to Cuffay. It is now in the People’s History Museum in Manchester.

In the Tasmanian footsteps of William Cuffay, by Mark Crail, Chartist Ancestors blog, 22 April 2020, is a first-hand account of a visit to Hobart, Tasmania, in search of Cuffay.

“William Cuffay in Australia” by Mark Gregor, in Tasmanian Historical Research Association papers and proceedings 58(1), April 2011 (accessed 10 August 2024).

Celebrating Medway’s black heroes on The Historic Dockyard Chatham website reports on the unveiling of the plaque to Cuffay and his fathe (accessed 10 August 2024)..